Australian artist Bill Henson on suggestive dimensions and a universe beneath the skin.

"The critical thing you must always remember is there is a profound difference between intimacy and mere familiarity … Mere familiarity doesn’t interest me, I’m not even trying to make a portrait of the individual, they’re anti-portraits. I’m interested in the universal items, the abstracted business of humanity, rather than a particular portrayal of an individual.” Photographer Bill Henson has never shied away from the divisive. Renowned for his masterful command of chiaroscuro (the contrast of darkness and light), his portrayal of models – regularly adolescent, often seemingly nude – and crepuscular landscapes, the artist’s oeuvre has been described as voyeuristic, mesmerising, pornographic, tender and disarming, all in the same breath.

Henson is aware of the affect his works have on audiences – the 2008 media furore over an exhibition at Paddington’s Roslyn Oxley9 gallery isn’t a subject he goes to great lengths to avoid – but he is candid about his intentions when creating his painstakingly, almost painterly, prints. “I don’t consciously anticipate the audience when I’m working in my studio, I’m just off on my own trip,” he explains. “Obviously we are all programmed to a time and place so we are all conditioned by where we are and our point in society and history. But I don’t have an agenda in that respect. My agenda is to do with the picture I’m making.”

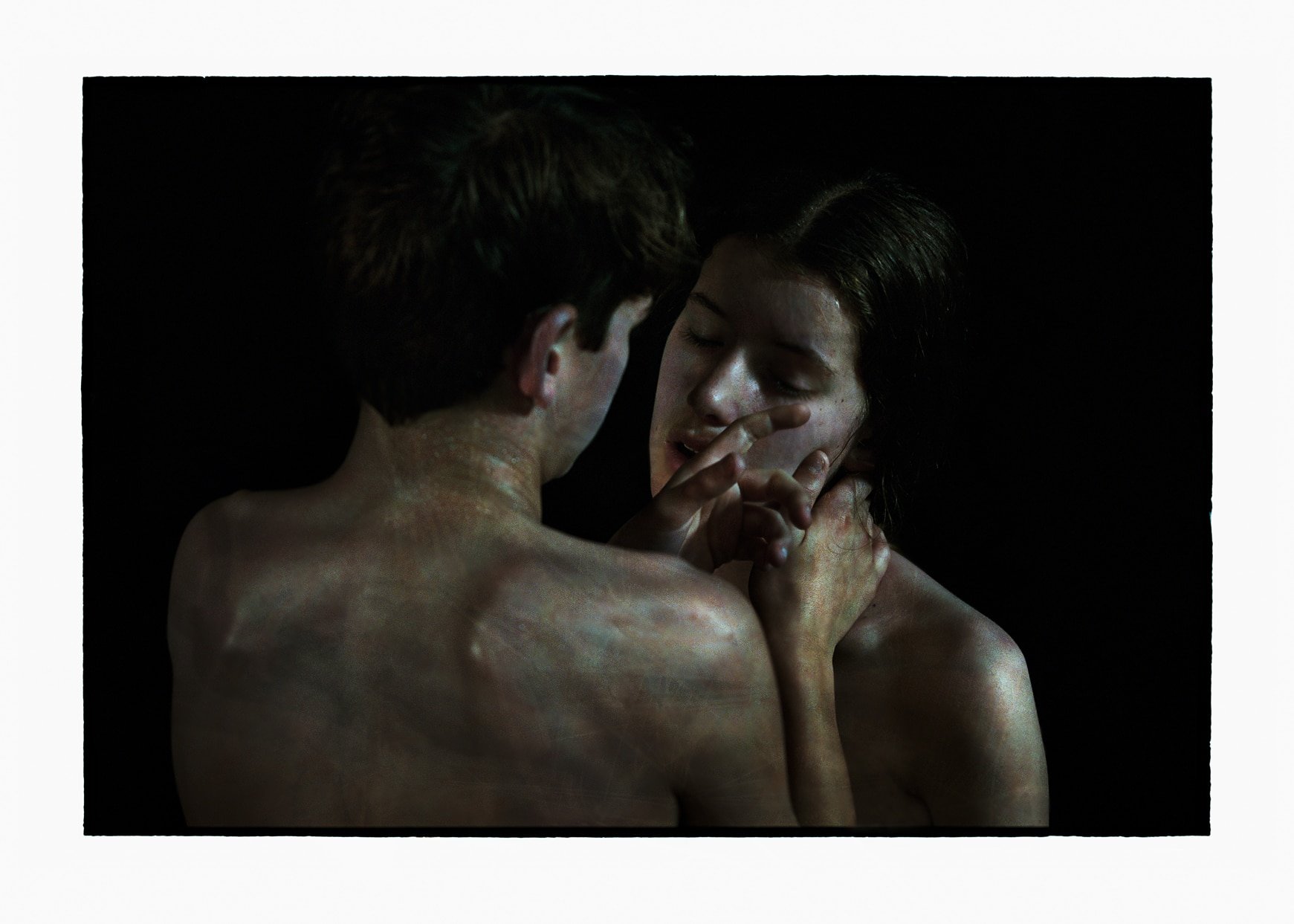

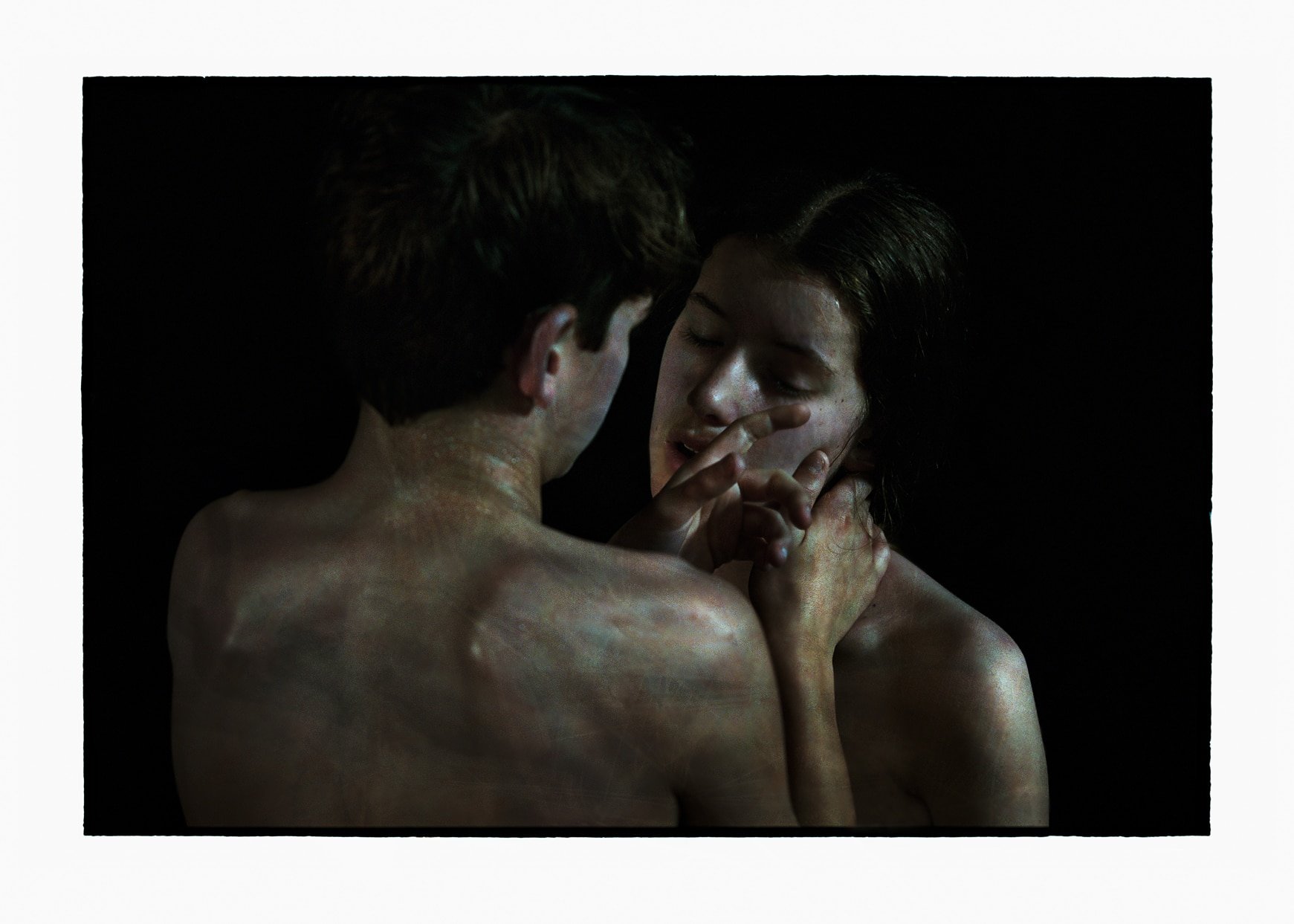

Henson’s latest solo exhibition (again at Roslyn Oxley9) is his first in Sydney in seven years, and features captures of Italian landscapes – ancient ruins caught at twilight or cliff faces tumbling into the blue sea below – alongside his signature portraits rendered against inky nothingness. A girl rests her face against the hands of a young boy, eyes closed, expression soft, their skin bathed in bronze and lit from within. What life exists inside these shells? What galaxies unfurl beyond the barriers of our earthly limitations? “It’s the suggestive dimension in any work of art that obviously opens up the space for the imagination,” Henson says of the trademark colour modulations he imprints upon the skin of his mortal subjects. “Exactly where does the world stop and we begin? Where do we end and the rest of the universe begin? That whole sense of a heightened sense of mortality, not morbidity, but being inside your body and spending your whole life trapped inside your body, you come to understand what happens with the skin … And it’s limitless.”

“People find the most effective vehicle that they can to articulate what they understand about things that haunt their imagination, or fascinate them.”

How do you feel you have changed in the past seven years [as an artist], if at all?

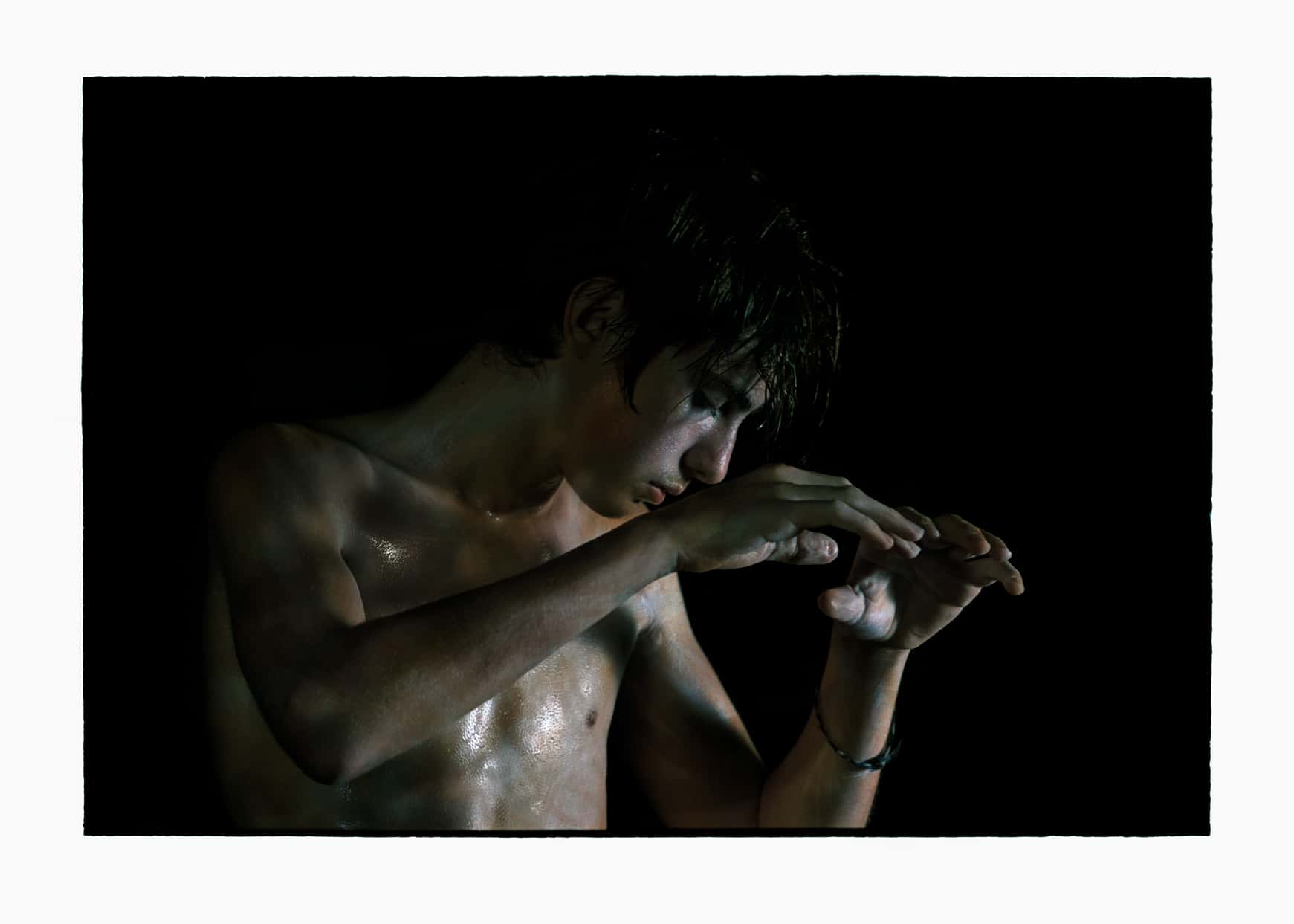

I don’t think I have, because every new work grows out of another work. There’s pictures here from a year ago, and there’s pictures here from six or seven years ago, and they just accumulate in my studio, build up in sedimentary layers. New ones grow out of old ones, associations grow between pictures, conversations start between different pictures when you put them next to each other … it feels if anything as though it is becoming more reductive formally ... Going back earlier, the pictures, when there were human subjects, there was a sense of the landscape around them. The city lights and things like that. And that seems to have disappeared out of the picture. Now these forms, faces and bodies, are just surrounded by blackness. There is a detachment from the world that is going on. That is a change that’s gradually occurred in the last 10 years or so. What it signifies exactly, I’m not sure.

Regarding the types of models that you photograph and their age, what role does youth play in communicating your vision?

Look, different artists require different things, and people find the most effective vehicle that they can to articulate what they understand about things that haunt their imagination, or fascinate them. For me, it’s about finding the necessary subject components, it might be a volcano, it might be a 12-year-old boy in a skate park. It just depends what I think is necessary, and then I go in search of it.

The thing about that age group that is interesting for me is the perfect microcosm for society in general, for the macrocosm. At that age, they are rapidly developing an independence from their parents, they are no longer attached to their mother’s hand, there’s an exponential growth both physically and mentally, emotionally. All these things produce a very dynamic fluid world, or a floating world, where there is tremendous potential. Suddenly they can get on a train on their own with their friends and go into the city on their own, suddenly all these things are happening in their lives, they don’t have to be tucked into bed at 7pm by their parents. There is a great potential, and of course there is a potential to go well or badly. And that, in some respects, references the great potential we have in our society for amazing things to happen or terrible things to happen. It seems to be just so many aspects of that age group. It’s also an almost androgynous sense of that age group, a sense that their development as a human being is not so clearly cut down as to one gender or another; they are still evolving in terms of their gender identity. All these things are much more fluid and ambiguous. And that makes it much more interesting, the ambiguity is what throws up the questions. What if? Who are these people? Where is this? What’s happening? By opening up all these questions, you create a space where people can have this imaginative journey. If you try to bolt it all down, it’s basically propaganda: ‘There you are, bang, that’s exactly what I wanted to say, you get it and it’s over’. It’s not interesting.

Your works evoke a sense of the mythical. How does that connect to the real world, in your eyes?

Well, we all have this vast inland sea of a subconscious, and it throws things up occasionally, you know? And it’s just like when we dream, what is that? It’s part of that vast inland sea that is only partially understood, if at all. And it’s in everyone. So you have this life you live, and you also have this life that you dream. You want to be able to slip back and forward between the two. The external world of stop at a red light and go at a green light, which we need as a society to function physically during the day, and the private interior world that we all have which is an emotional and intellectual and spiritual place that has a massive primal conditioning effect on how we feel about ourselves and our place in the world. How we interact with all the beauty and complexity around us. And that is always there. So of course you want to suggest that in some way. In trying to suggest it, the only way to suggest it is to not prescribe it. All you can go is ‘What is that?’. When you wake up and have that clear taste of a dream, and you can remember parts of it, and it’s the incredible business of how the dream evaporates, and then an hour later it’s impossible to pull back the detail that you had. And that’s going on inside everyone all the time. As we walk down the street too. That’s that interior world. You need to be able to suggest that. That is where the depth and humanity comes from. It comes from the things we feel but don’t understand.

Do you believe in the soul?

Well, I don’t think of it in a simple individuated way. I feel like, for a start, culture is never outside nature. We are inside our culture. But our culture is inside nature. And it flows through us. So all those philosophical arguments that treat us as if it’s gone down through the centuries, and suggest that there is only the present, or a past and all of that stuff is real ... Of course it’s real, we can have the thought and the feeling. I don’t think I spend much time thinking about it in those terms, as an individuated thing … I think yes, there is this presence, there is this energy, you can call it whatever you like …

“You have this life you live, and you also have this life that you dream. You want to be able to slip back and forward between the two.”

But you don’t dwell on it too much?

I’m always interested in the way we feel things. We have these ‘apprehensions of significance’ I think I called them, it’s like something that has a powerful effect on you but you just can’t be quite sure what the parameters are. Some people have more or less a clear idea of what they think, conviction about something. I find things become stranger. It’s the beauty, and beauty is the agent of love. I like to say that the universe runs on attraction, between two molecules in a vacuum all the way up to an episode of ‘Hollywood Housewives’. It’s all about attraction. And I think this is what makes things, this is how particles behave in our universe. So we are a part of this. We always have subatomic particles running through us the whole time. So where we begin and the rest ends, where we end at our skin and the rest of the world begins, I think is less certain than we’d like to think. So that individual thing is far more uncertain. And that’s one of the reasons why I [use] the technique of destabilising the skin and the flesh and introducing a translucency into the pictures. To make it less certain that these people are in the physical world. That they’ve come from the world of the imagination and into the physical world, to make that remarkable trajectory less defined and less certain. There is a great writer called Elias Canetti who was a contemporary of Sigmund Freud, who got out of Vienna when the Nazis came, moved to London, won the Nobel Prize. And he used to say sometimes facts emit a destructive force. I like to interpret that as the fact that things can be powerfully apprehended but not necessarily understood. So I think it’s a more interesting journey that we go on. It leaves you more open to things.

How do you hope people feel or respond to the exhibition?

It’s not for me to presume to understand how a certain picture will effect a certain person and why, because I haven’t spent 20 years in your head. I say to school kids sometimes, there’s a picture of a road going off into a very dark forest, and the way I explained it I said, ‘Look, I made the picture, but the way it absorbs your attention, it is basically your road’ … This is one of the great gifts of art: it reinforces the priority of the individual experience. It puts you back on yourself sometimes.

On that photo of the dark road – you have long-been fascinated with depicting shadow and darkness in your photography. What is it about the dark that you find so compelling for your work?

You can be very, very basic in talking formal terms and it’s like the negative space in a picture, because there’s no information there, just blackness. But that is information because the blackness has a form, it has an edge where it ends and the light part starts. The contour of a body changes and slips into shadow. I think darkness is just one of the things that an artist can use to introduce unknown spaces around known areas. It’s like having a clearing in the jungle; you can see the sky and then you go into the jungle and you can’t see very far. There are certain tribes that anthropologists studied that spent their whole lives in the deep jungle. They had no ability to judge vast distance because they could only ever see 20 metres in front of them. So the blackness or the shadows carry a great suggestive potential. Sometimes there’s a bit of information, but your imagination is building things into the space. It’s about expanding the space into which you can go on a journey, I suppose. That’s the main thing that the darkness does.

All imagery courtesy of the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney, Australia.