I’ve been a model for more than four years. On runways, in editorials and in advertising I’ve modelled amazing clothes, hideous clothes, frumpy clothes, sexy clothes … Nevertheless, the common denominator has always been the clothes. So what would it mean to get rid of them?

The idea was unnerving. For the duration of my career, I’ve been told what to wear and how to wear it. Who to be, what guise to adopt, how to seduce and how to sell; a product, a dream, a lifestyle. After years in the industry, I realised that I’d lost touch with my body – it had absorbed the identity of its environment, leaving me feeling disconnected with the most intimate part of myself.

When the opportunity arose to model for a friend’s life drawing class, I saw a chance to examine this relationship – the one I had (or rather had lost) with my physical self.

Ironically, during my teenage years I was renowned in my family for being the most vigilantly anti-nudity.

My first experience with life drawing was in high school. At my stuffy all-girls boarding school, the art staff were the epitome of cool. They were the ones who let us smoke on school trips, took us to London to see exhibitions, let slip wild stories about their past lives before they became teachers. Life drawing classes were a weekly opportunity to spend time with them.

I remember hearing stories about the model long before I met her in the flesh – and fleshy she was. A crinkly, seventy-something woman with a short crop of silvery hair sitting proudly before the class wearing nothing but a pair of earrings. Her name was Gilda and she was fabulous to draw. Her breasts rested on her tummy, and her saggy skin was a joyful testament to a life lived and experiences had. In that room, she was no longer dismissed as “old” or “flabby”; she became a goddess of line, shape and shadow.

Being the giggly schoolgirls that we were, we would nervously joke about who Gilda would choose as her target each week. Each session, she would select one of us with whom to engage in an hour-long staring contest. There was something so intimidating in her gaze. The way she carried herself defied the expectations of prudishness and propriety that had been drilled into us by the school. She sat before us completely naked, devoid of shame, self-consciousness or perfectionism. She was not vulnerable or meek, but empowered.

Ironically, during my teenage years I was renowned in my family for being the most vigilantly anti-nudity. I would lock myself in bathrooms to change, never allowing anyone to see my body. I was acutely aware of my transition into adulthood and, in true teenage style, I found the changes mortifying. When I began modelling in my 20s, I was freed from these hang-ups – I was dressing and undressing so often that my old attitudes fell away. Nevertheless, while my views on physical exposure relaxed, emotionally I remained the awkward teenager barricaded in the bathroom. What posing for my friend’s drawing class offered me was not only an opportunity to confront my physical form, but also a chance to undress emotional blockages.

The experience itself was, if anything, rather nondescript. I arrived at the venue and was introduced to the students. I was then shown to the bathroom where I put on a robe, which I removed once the class began. During the session most of the artists were hidden from view by their easels. Heads would pop out intermittently from behind them, peering studiously at my body with an almost comical expression of sincerity.

No one called out at me to “smile!”, “smoulder”, or – like one of my more cringeworthy experiences – to “stay beautiful!”, as a photographer repeatedly yelled at me (while also instructing me to leap around maniacally). There was nothing to sell, so there was nothing to advertise. There was no stylist tweaking my clothing to remove creases, or so that the logo could be seen. To be honest, it was a little boring. I’d been so conditioned to pout and pose, to embody an aesthetic or an idea, that I didn’t really know what to do with myself. It was humbling to see how little effect my body had on the group.

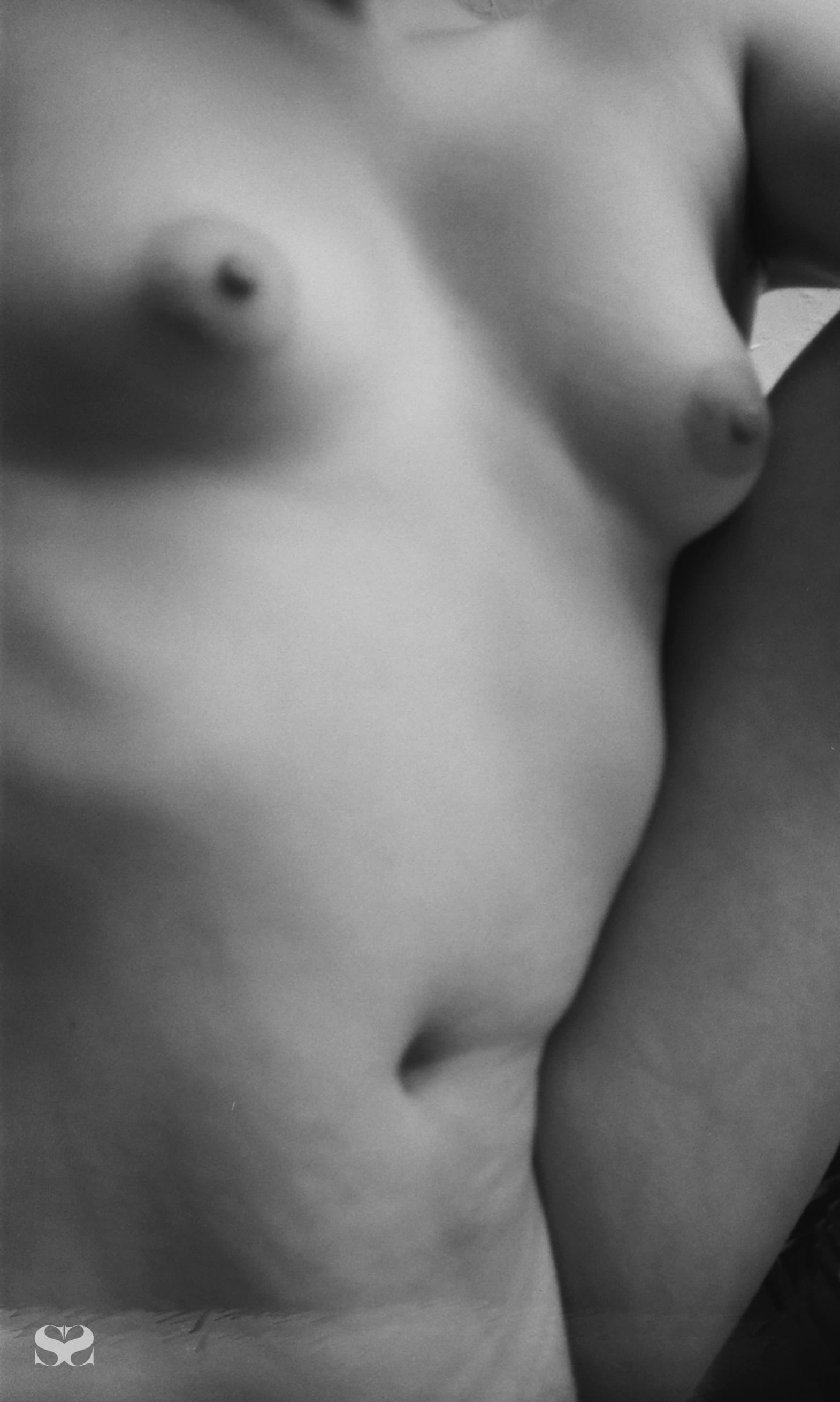

During the breaks I would put on my robe again and walk around to see what the students had drawn. Like my previous experiences of modelling, it was fascinating to see the variety of interpretations my body provoked. The feeling was different, however; less charged with expectation. Unlike on shoots, there was no agenda. I wasn’t looking with the same critical eye, the scrutiny that had become second nature in the fashion industry. The two different types of modelling revealed two different approaches towards my body, and my conceptions of physical beauty. In the fashion industry, beauty is measured against a prescribed standard; the closer you are to the mould, the more beautiful you are deemed to be. In life drawing, the sitter is the mould; whatever they present sets the standard.

I suppose an unavoidable element of this exploration includes my own attempt to adjust to myself after a period of physical change. In the past I struggled with an eating disorder, something that was as much a means of emotional control as it was a product of my industry. I manipulated my body into a state of arrested development; I lost my curves, my period and my sex drive – all things that might define my womanhood and sexuality. This prepubescent state was like a twisted emotional safeguard, protecting me from the reality of adult life.

Returning to my natural size brought up many realisations about the nature of mind-body connection, both personally and societally. I realised the extent to which, as women, we are taught to repress our bodies. I realised the weight female flesh holds in society; how taking up space, both physically and metaphorically, is still considered outside the domain of “femininity”. I noticed the link between aesthetic perfection and a sense of “worthiness”, and how often the female body, particularly its size and shape, is used as a dumping ground for shame.

Traditionally, the woman is supposed to be a passive figure. Throughout history, the female form has been depicted as idealised and eroticised, but in a way that places the ownership of that eroticism in the hands of the male onlooker. Female sexuality is sanctioned only as is deemed acceptable by proxy of the male gaze. In other words, we can be sexy, but only if men say it’s OK.

Female sexuality is sanctioned only as is deemed acceptable by proxy of the male gaze. In other words, we can be sexy, but only if men say it’s OK.

A woman in control of her own body is a dangerous entity. Throughout history, the female nude has been a primary example of the expectations placed upon women, their bodies and their sexuality. The female nude is construed as a goddess, idealised, hairless and the property of her male counterpart. Google Titian’s Venus of Urbino and you’ll see what I mean. The texture of her creamy skin is equal to the richness of her surroundings – like the opulent interior, she is simply another one of her husband’s expensive possessions. Her body exists as an object to be admired and consumed, not something she herself is in command of. She is the emblem of passive femininity.

Granted, this is a traditional example. And yet even in modern contexts, the female body is objectified through a male lens. Female sexuality is used to advertise everything from clothes, to cars, to yoghurt. The effects of the male gaze are so deeply ingrained in our culture that women are forced into a cycle of patriarchal consumption – ranking ourselves and each other against beauty standards we didn’t even choose to aspire to in the first place.

Even in fashion, with its focus on thinness and youth, women are denied their reality as ordinary, human bodies. We are either hyper-sexualised or desexualised, jarring awkwardly between the binary of slutty and saintly, promiscuous and pure.

In an interview on the “Nudity” episode of the BBC’s The Why Factor podcast, Inna Shevchenko of activist group Femen explains the group’s now infamous style of topless protest. “It’s a peaceful weapon but also a very aggressive weapon to both the system and the society,” she explains. At her first topless protest she describes how she didn’t feel naked, but rather “as if [she] was wearing a special uniform”.

A naked woman remains a powerful symbol. Perhaps this is because we still consider nudity synonymous with eroticism. Yet ironically, the experience of modelling nude couldn’t have felt any less erotic. After the initial awkwardness, it felt totally natural. Unlike previous modelling jobs, I was there to be studied, not to seduce. Yet there was still a part of me that felt uncomfortable with the idea of nudity. I felt embarrassed to admit to people that I’d posed nude, as if it were something dirty that I should feel ashamed to confess.

“You can feel profoundly exposed, even while very clothed,” explains Sydney professor Ruth Barcan, interviewed by presenter Mike Williams on the same podcast episode. According to her, nakedness is not just about clothing, but rather “how exposed you feel to a gaze”. Certainly in my experiment this proved true. When modelling for the life drawing class I was protected from the prying eyes of the patriarchy, safe in an environment that wanted my body for nothing more than its ability to cast a form on a page. Fashion modelling, on the other hand, made me painfully aware of my place in an industry, and indeed a society, that continues to foster the objectification of women and their bodies.

To own one’s body is to own its humanity, including its innate sexual potential.

Williams comments that “the process of disrobing is as powerful as the nakedness itself”. We spend most of our time covered by clothes, so to remove them is an act of titillation. Perhaps that was why I felt uncomfortable telling people that I’d posed nude – because I’d made the active choice to expose my body, to undress. Something in my brain tied this decision to a feeling of indecency, linking nudity with sex, and sex with shame.

Again this notion of shame. I realised that shame is the primary tool used to control women. To own one’s body is to own its humanity, including its innate sexual potential. A woman in command of her own sexuality is liable to be shamed, not only by men but by other women, too. She is considered dangerous, amoral, a threat to traditional notions of passive femininity. We don’t know how to handle a woman who is active rather than passive. A woman who is forthright in her opinions is loud and brash, opinionated, “too much”. Hormonal or hysterical. Meanwhile, a man who behaves thus is authoritative and assertive. A player. A leader.

As part of my research for this piece, I visited the Tate’s exhibition All Too Human. The show featured many nudes, both men and women, painted by the great Lucian Freud. What struck me about Freud’s work was his lack of shame. He didn’t make any attempt to hide his impulses. He painted nudes with a visceral, passionate energy that saw the body for what it was: a machine for living that could be both beautiful and grotesque. His nudes are full of skin, sex and emotion; the physicality and the feelings that made both him and his sitters human.

Even at my all-girls boarding school, the male gaze won out. After weeks of drawing Gilda, she was replaced by a new model, Angie. Angie was an attractive twenty-something with big boobs and a Brazilian, undoubtedly selected by the male heads of department. Drawing her toned physique held none of the same fascination. We missed Gilda, her craggy crevices, her landscape of a body that was more Freud than fashion.

In our age of “body positivity”, it is demanded that we should “love our bodies” at all costs. It suggests that if we don’t, it must be because we feel the opposite.

What my own investigation gave me was not so much answers as acceptance. A peaceful neutrality. An understanding that my sense of worth as a woman does not come from a place of either defying or adhering to an aesthetic, loving or hating, or choosing between brain and body. Such rigid categorisations only trap me in a vicious cycle of comparison and control.

The only choice I need to make is to actively listen to my body; to amplify the inner voice above the outside noise. While I cannot completely shake off the pressures of my environment, I can remain conscious of finding my individual self within it. These days, instead of striving for Angie’s body, I’m listening for Gilda’s liberation.