"Life shrinks or expands in proportion to one’s courage.” – Anaïs Nin.

The world, contrary to the fairytales of our childhood, is not populated solely by swashbuckling heroes and whimpering cowards. I find myself – like, I assume, a large percentage of others – stranded somewhere midway between the two: wishing to be brave while feeling easily afraid of things that are out of my control. Those in the performing arts, sufferers of chronic illnesses and emergency service personnel face danger and fear on an almost daily basis. But what if the panic is due to a feeling that is intangible, irrational. What if your terror is that of the elusive great unknown – you are afraid of what you do not recognise and cannot control?

I have always been cautious. I plan. Without thinking I am constantly projecting myself ahead of the present – an hour, a day, a year. I don’t enjoy it but I find it impossible to stop, it is a way for my mind to grapple with the future, to attempt to quell my fear of the unknown and uncontrollable. I sometimes picture myself in worst-case scenarios – crashing, falling, failing – almost too vividly, and my chest begins to tighten as I start to accept this alternative reality as actual reality. I think of myself dying – something I’m told is not uncommon – and while the specifics change it is always too soon, I am always too young. My head and my heart ache when I imagine my loved ones dying, of receiving phone calls telling me they are gone. There are times I am afraid that I won’t like my future life, and I am permanently afraid of making the wrong decision. My future projections build a tiring cycle, one that exacerbates my anxieties rather than alleviates them. Fear, like salt or MSG, seems to work best in small doses – sprinkled throughout one’s life as opposed to characterising it. It is exhilarating to overcome a small fear – ‘character-building’ – but when the minutiae of day-to-day living is all it takes to have you running for cover while others seem to be breathing easy, could there be further moral or biological elements at play? Are some minds preconditioned to be brave and others to be fearful? And, importantly, is bravery something I could continue to learn?

There are five distinct and automatic reactions humans experience when feeling fearful according to trauma psychologist David V. Baldwin in his 2013 paper “Primitive Mechanisms of Trauma Response”, published in Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. Depending on the level of threat we interpret, these are freeze-alert, flight, fight, freeze-fright, and collapse.

It is a flexible system, Baldwin has found, in which we can change our response instinctively if the one we initially choose isn’t working. When we are stressed, or feeling fearful, the primitive brain takes over from the rational brain. This is why we sometimes find ourselves unable to explain our physical and emotional reactions when confronted with something that scares us; we are at the mercy of our primitive minds. Knowing this to be true, that we cannot necessarily blame ourselves for our immediate reactions when confronted with fear, why is it still that some people are able to charge into the fray – the burning building or the barside brawl – while others find their immediate reaction is to turn and run?

Are some minds preconditioned to be brave and others to be fearful? And, importantly, is bravery something I could continue to learn?

Dr Simon Kinsella, an honorary fellow in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Melbourne and the School of Psychology at Deakin University, assures us that anxieties, fears and phobias are extremely common: “Almost everybody has the capacity to feel fear in the right circumstances. For some people the threshold is a lot higher than for others.

“The most common fears are issues like fear of public speaking, or fear of failure. Other common fears are fear of flying, fear of injections and fear of crowds. Also, for people who have had a panic attack, there is a possibility of developing a fear of another attack happening – a fear of fear.”

Though Kinsella admits it is not entirely known what controls our ability to be brave during fearful situations, he adds that, “We know that certain things will influence it, like previous exposure to danger, underlying personality and pre-existing mental illness.”

There are a number of elements to consider when understanding why people react differently when presented with the same frightening situation. Biological factors are important: “If you are a fit and capable person, you are more likely to believe you can intervene,” says Kinsella. “Personality factors are important. If you have a high sense of competence you are more likely to act,” rather than to run. He also explains that social factors are highly significant when evaluating different reactions. “There is a bystander effect such that an individual in a group is less likely to take action than an individual alone … Also, there may be a greater chance of someone acting bravely if a loved one is in danger.”

Training to act bravely is dependent on the situation you have to prepare for. Kinsella suggests if you can gradually expose yourself to things that cause increasing levels of fear, and use psychological tools to manage fear along the way, you put yourself in the best position to manage that fear. “Preparation is a critical factor in preparing your mind,” he says. Knowledge is a form of power, and when we feel powerful we feel braver. Research, reading, watching the news, and gently immersing yourself in what frightens you can all aid in the quest for bravery. Visualisation is another tool he recommends using when trying to overcome fears; visualise what success would look like and how you will succeed.

What if your fear is that of the elusive great unknown – you are afraid of what you do not recognise and cannot control?

“When we take time to just be still and quiet with ourselves, we find more trust in the universe and in ourselves with our journey.”

Physicality is just as important as mental health. Kinsella asserts that a person’s physical condition has a direct impact on their ability to act bravely. “Healthy life practices are important,” he says. “Being fit, having adequate sleep, reducing drugs, alcohol and caffeine, practising yoga or meditation are all things you can do to keep your base level of stress as low as possible.

“This means that when something stressful does happen you are most likely to be in the best condition to cope.”

Kinsella is clearly not alone in his commendation of a mind/body balance. Gini Eagle, a Reiki master, yoga instructor and writer, has been practising Reiki – a system of healing that aims to balance and align a patient’s energy system – for more than 20 years, and suggests that this is another way to clear our beings of entrenched fears.

“Every person I see is dealing with some sort of fear. And it’s very much to do with your connection with yourself. With your true self,” she says. “We all have an energy system, which is made up of auric fields and our chakras. And when we have traumas or different problems in our lives our energy system gets blocked. Reiki helps to relieve all those blockages.”

Reiki, developed in Japan early in the 20th century, is ‘hands-on healing’; the patient lies on a table and Eagle places her hands on the bed, as well as on and around their body, tapping into their energy fields and acting as a channel for a higher frequency of energy: “I’m channelling light into the body and their energy field, and helping relieve lower energy if it gets stuck.”

Eagle believes the first step in training yourself to be brave is to acknowledge that you feel the way you feel. “If you can get to more of the root of the cause [you] see that the fear is generally unfounded,” she says. “There’s a saying called ‘false evidence appearing real’, something that is just a pattern or a vibration of energy that’s been imprinted from a perception that we’ve had or a worry [about] something that we think might occur, and it’s not real.”

Acknowledgment of the fear also includes where you feel the anxiety in your body: “You know the old saying … ‘having butterflies in your stomach’ or your stomach ‘tied in knots’. So finding where the fear is and then breathing into it, deep breathing into that place where the fear is,” she says. “Imagine that you’re breathing in energy through your head and then breathing out the essence of fear.”

Other tips include embracing the importance of being mindful and how to bring yourself back to reality when fear takes your thought process off course – glaringly prevalent in my own particular case. “When your mind starts to race off and you imagine all the things that could go wrong,” she says. “Just naming some things around you, you know, ‘there’s a tree, there’s my desk, there’s someone standing over there’. Just being really present and bringing yourself back to the moment.”

Another technique employed by Eagle is to have the recipient write down their fears and then literally burn that piece of paper. She encourages them to use an affirmation, ‘I release the energy of these fears, or I release these old patterns. I’m safe, all is well in my world. I have the courage to do whatever I need to in my life.’ Nature also plays a pivotal role in aiding the release of our fears. “Just lying on the ground or sitting beneath a tree helps to release that pent-up energy of anxiety and worry. Breathing into Mother Earth, and she just gives back energy to you.”

Through an understanding of both psychological and holistic approaches to acquiring courage, we can see that while brave people may be built differently, it’s not impossible to become bolder. Bravery is not being born with the absence of fear, but rather understanding how to manage it within your own space; to acknowledge it, accept it and push beyond its barricades. To actively expand our universe, rather than watch it shrink before us.

The last time I felt fearful I sought out nature. I went to the beach early on a Saturday morning, before the hordes had arrived, and lay in the shallows while the water ebbed and flowed over my body. My chest expanded with each wave that washed over me. And now I am trying to acknowledge my fears, as irrational as they may seem, by writing them down. I haven’t set them aflame but I have sent them to print, which feels cathartic enough for now. I’m trying to remember the affirmations: I’m safe, all is well in my world.

While I may never be wholly emancipated, for now, I will be still. “It helps you to reconnect with your divine intelligence,” explains Eagle. “When we take time to just be still and quiet with ourselves, we find more trust in the universe and in ourselves with our journey.”

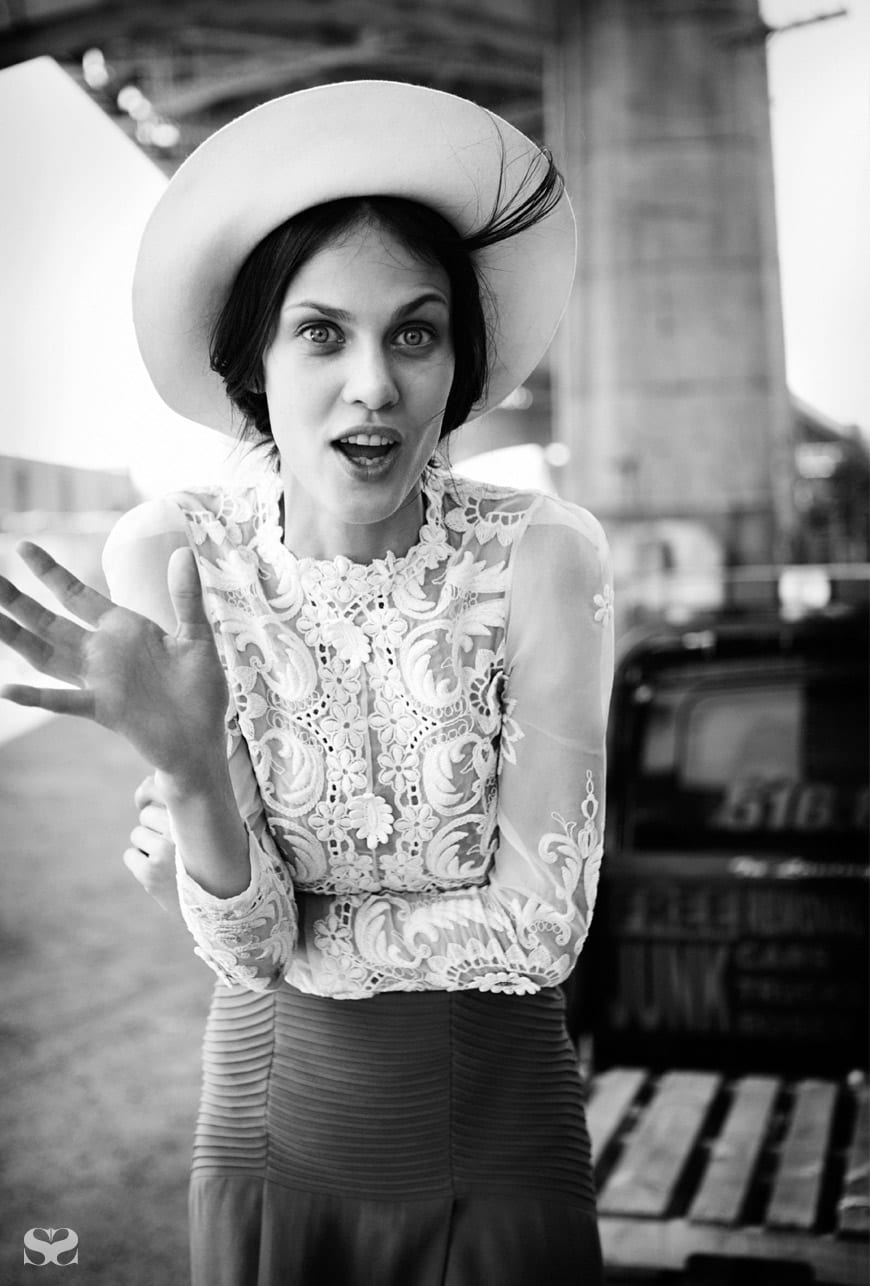

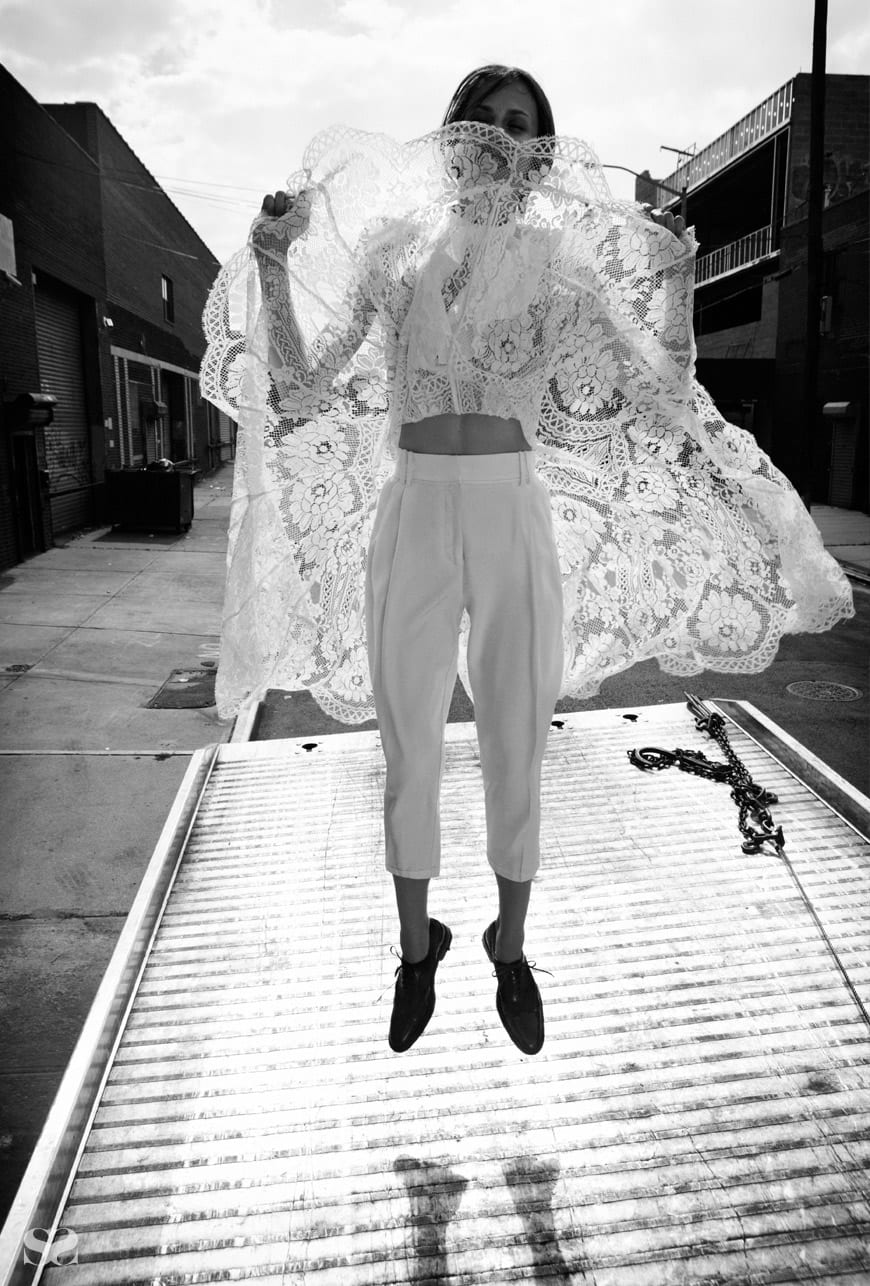

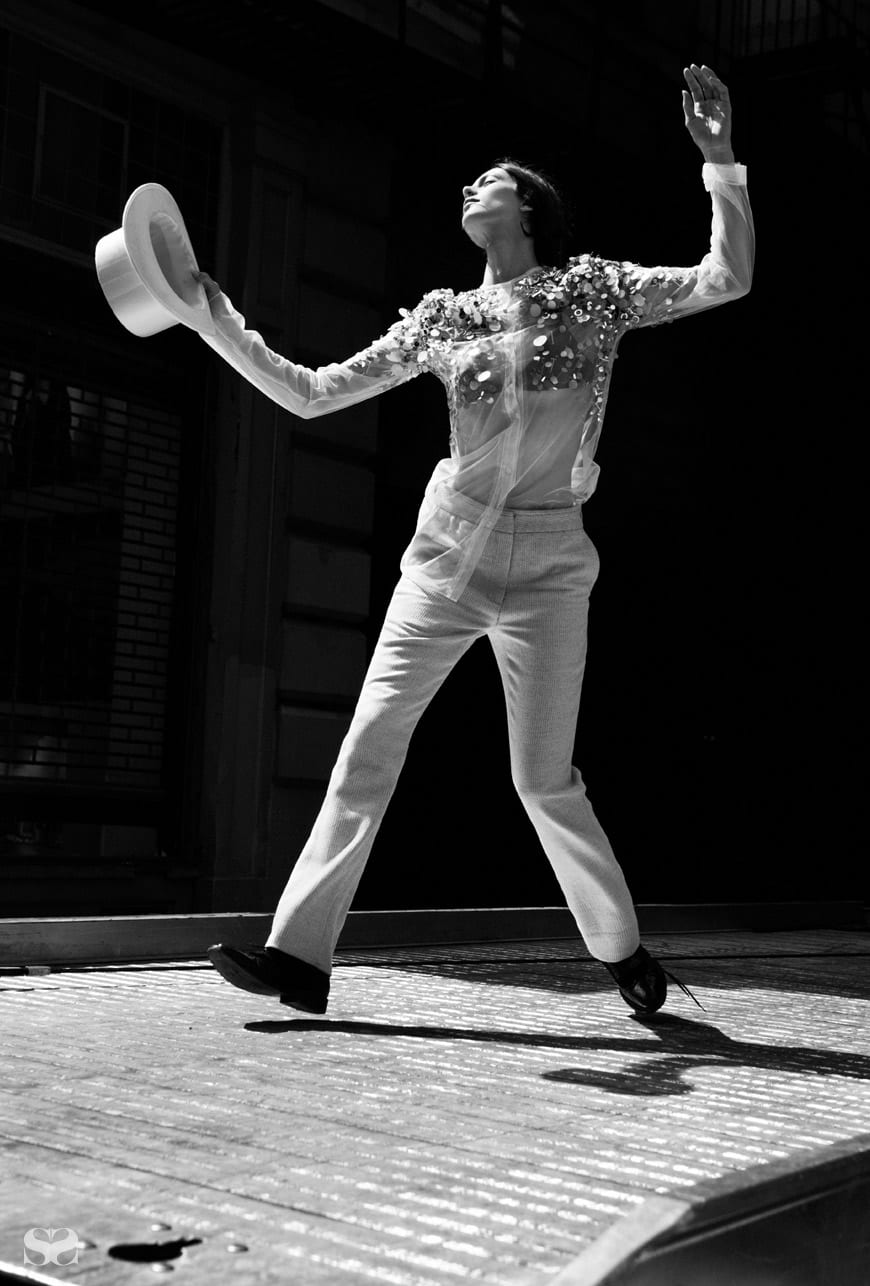

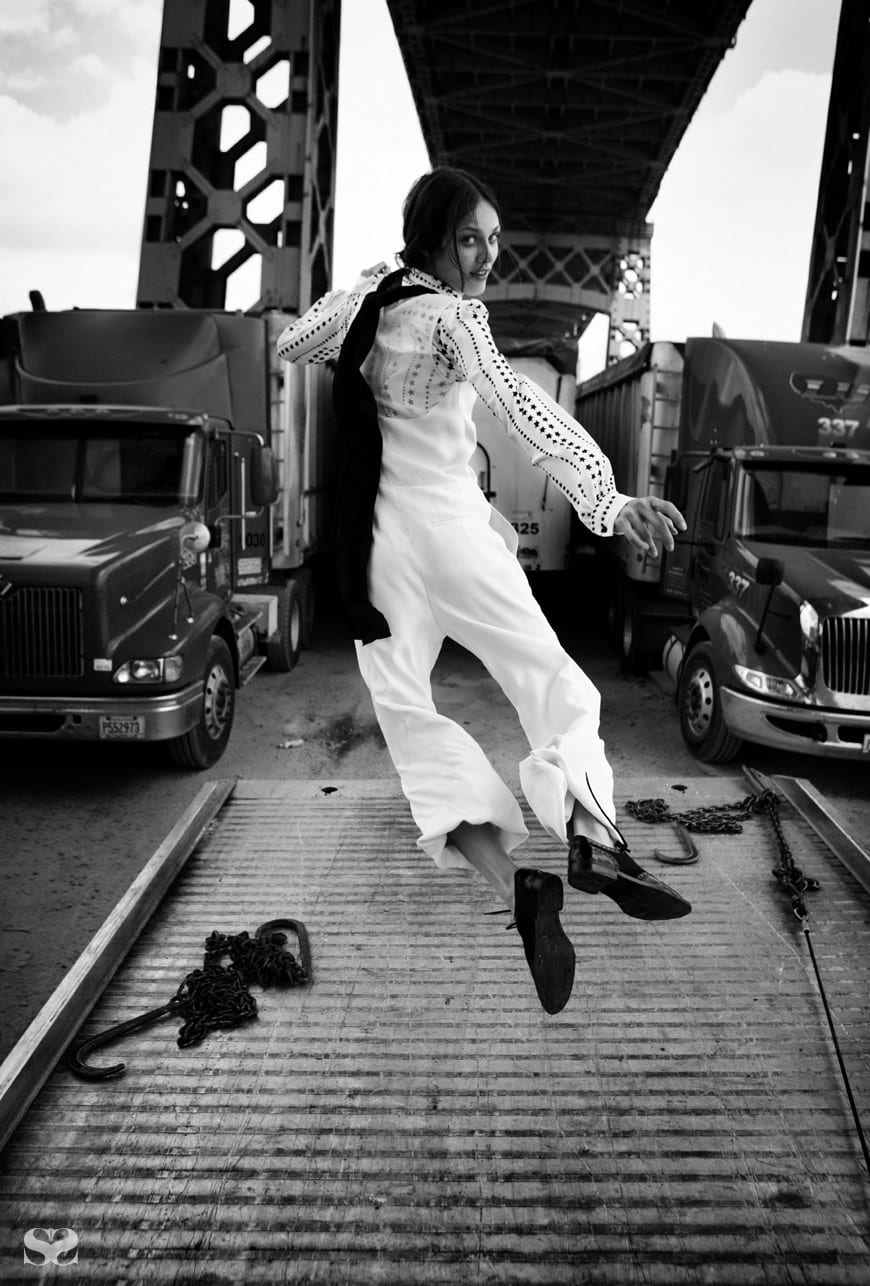

PHOTOGRAPHY Will Davidson @ MAP

CREATIVE DIRECTION Stevie Dance

MAKEUP Chiho Omae @ Frank Reps

PHOTOGRAPHER’S ASSISTANTS Benedict Brink, Andrew Peters and Nyra Lang

STYLIST’S ASSISTANT Sasha Kelly