Solomon Kammer isn't here to paint flowers. If you want beautiful artworks to hang on your wall "you can paint them," they tell me. "I don't mind." No, until all people can live peacefully, art will continue to be a place of protest for Kammer.

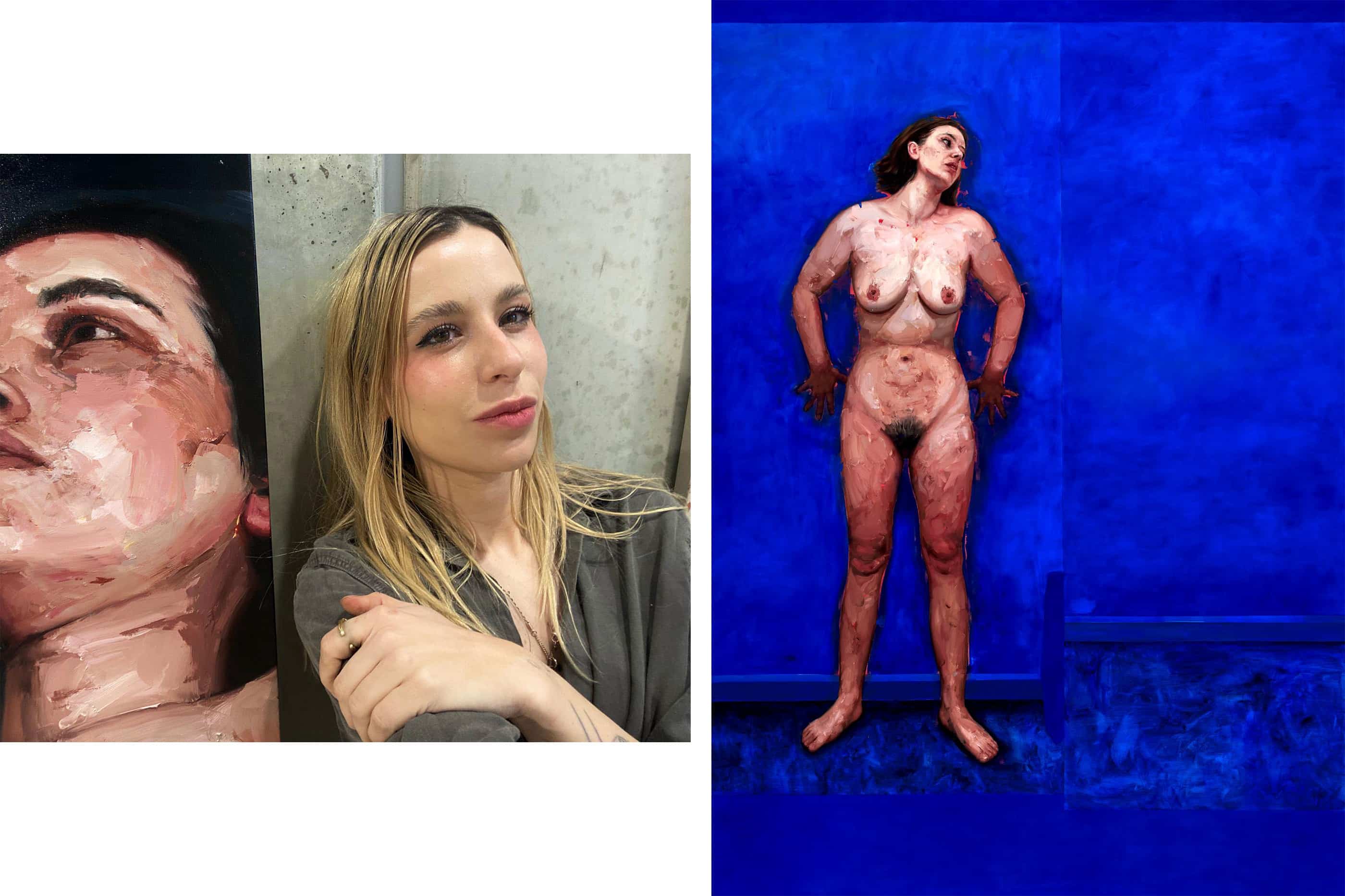

Some people will label Kammer's fleshy nudes as confronting, even verging into body horror territory. And sure, past figures in the Adelaide-based painter's works have had blood marbled across their torsos, or as is the case for their first international solo show Give It Up at Yavuz Singapore, fingers pressed forcefully into the subject's mouth. Figures lay scrutinised under prying eyes, their bodies exposed yet their eyes defiant. But as you'll soon learn, that is the point.

"Making art has always been a means of coping with my environment and experiences," Kammer says. Whether that's sharing their experience of being diagnosed with ADHD, relaying the ways in which the medical system has failed them or by bringing to light how both disabled and queer people must constantly fight for agency over their own bodies. What links each of Kammer's works is their desire to challenge society's view that certain bodies are "more sacred, valuable and worthy of protection than others".

With Give It Up currently showing at Yavuz Gallery, Singapore, RUSSH caught up with the 31-year-old artist who spoke about burn out, studio rituals, bodily autonomy, Kate Bush and why they'll always return to Pride and Prejudice. Find our conversation, below.

What’s something you wish more people knew about you?

I don’t think I feel like people need to know about me personally, to be honest. I suppose if there’s one thing I want to clarify when it comes to my work it’s that I don’t make it with the intention of making something beautiful to hang in a home or to hold up a kind of Mirror of Erised to its viewers. I find I’m often challenged, usually by people who benefit from the systems that cause the damage I discuss in my work, to make work that is more uplifting and optimistic. I will make work that is peaceful and banal when the world allows all people to live peacefully... until then, I’ll be protesting in my own sort of way. I’ll never understand people who request that I paint something else – if you want flowers on your wall, you can paint them. I don’t mind.

How did you come into painting?

Making art has always been a means of coping with my environment and experiences. For the longest time I had difficulty explaining why I feel that making art is more a necessity than a desire for me and it's only recently with a retrospective diagnosis of ADHD and suspected autism that I understand why creating has been as vital as breathing for me. I have always had great difficulty communicating in the typical ways, as well as an overwhelming and unrelenting sensitivity to injustices. Image making is my safe way of communicating with the world, processing internal conflicts and finding peace in my pain.

In 2013 I started using oil paint as a medium and it felt to me to be the most immediate and visceral way of expressing myself. It feels like a very natural extension for me. In 2015, I was confronted with my most difficult life hurdle yet when I was diagnosed with an incurable chronic pain disease. I processed it in the only way that I could, through making images, and I exhibited these works in my debut painting solo exhibition at Light Square Gallery in Adelaide in 2016. Presenting my life in this way was a profound experience and the public response was humbling and affirming.

Can you tell me a little about where you were at when you began working on this new series?

I had just come off the back of a significant year in my career. I’d been selected for the Ramsay Prize, obtained representation with a highly regarded gallery, presented my debut solo exhibition with the gallery and sold out, showed work in Art Basel Hong Kong and Asia Now Paris and I should have felt on top of the world, but like everyone else I felt exhausted, burnt out and the pressure to maintain my golden run was immense.

I took some much needed time away from the studio before beginning these works because I realised I was falling into the traps of trying to please the masses. The time away from the studio allowed me to reacquaint myself with my values and return to a place in myself where I could summon ideas more clearly and authentically.

What were you reading, watching and listening to while creating the works that would form Give It Up?

Reading: Pride and Prejudice. Over and over, forever. I can relate to wanting to do things on my own terms.

Watching: I have been on a murder mystery tangent for the better part of this year. I watch all the Netflix trends but my favourite thing to do is throw on a Bailey Sarian or Mr Ballen Youtube video. Short stories of intrigue are my go-to.

Listening to: For the record, I liked Kate Bush before TikTok! I can’t escape this trend though, I haven’t been mad about the resurgence of her work at all. Cloudbusting is on repeat at the moment.

Can you tell me about Give It Up in your own words?

I think what was perpetually feeding the creation of these works a phenomenon that was happening around me. All of my closest friends discovered their neurodiversity at the same time, as a consequence of me finally getting my own diagnosis and sharing my symptoms and experiences. Just like me, each of them went through stages that rather mirror the so-called ‘five stages of grief’ after the simultaneously validating and devastating realisation there had been a significant but undetected reason as to why they’d gone through life feeling like they were unwittingly sabotaging themselves over and over again.

What was especially painful to watch was how the system failed them exactly as it had failed me. They faced every barrier trying to access help. The year has been and gone and only one of them has been able to see the appropriate doctor and obtain a diagnosis and that is because she had access to my template as to how to circumvent all of the gaslighting, ignorance and stigma that consulting doctors would project onto patients seeking access to support for ADHD. The others are still months away from talking with someone who knows about the condition, and they’re saving up a small fortune to be able to do it.

I watched all of them squirm through the process – their mental health diving, their relationships with their bodies deteriorating, their confidence diminishing. I watched them believe they must be making it all up for attention after doctors mocked them for doing their own research on a condition, despite suffering the consequences of it never being detected by medical professionals. I saw them harden as they were forced to adopt the role of an advocate for their own wellbeing who won’t take no for an answer. I watched the system abandon them and leave them in perpetual despair. Even though I’d been through it all before, there was nothing I could do to practically help them and so I turned to painting to make sense of things as I always do. I had to shed light on what disabled people are subjected to and how they’re left behind in society.

Bodies are a constant theme in your work, speaking to coercion, agency and your personal experience of chronic illness and medical mistreatment. What is it about the body that you wanted to explore in Give It Up?

To put it as simply as I possibly can, I identify that society views some bodies as more sacred, valuable and worthy of protection than others. I take issue with this, of course.

In my own experience, I have had to give my body over several times; when I have been sexually assaulted, when I was medically assaulted, through invasive testing, through sexual coercion and grooming and through daily microaggressions levelled at women and gender minorities. In a medical context, when I first attempted to access care as a patient, I had some naive hope that this industry would somehow be immune to systemic misogyny and archaic gender biases. I thought that healthcare would prioritise patient well-being above all else – as it should.

My hopes for a fair and equal experience were dashed when I requested my gynaecologist discuss the steps I would need to take to evict my uterus (at age 27) as eviction is the only way to cure a medical condition (adenomyosis) I have that was causing me chronic pain, obliterating quality of life and hospitalising me regularly. This doctor refused to have the discussion with me entirely due to her belief that I wouldn’t know myself well enough to determine whether I wanted kids until I’m 30 years old. She told me to come back in three years. The doctor was more comfortable sending me home untreated to live in agony, be admitted to hospital frequently for unmanageable pain and internal bleeding, allowing my mental health to deteriorate and losing the ability to participate in my own life, than letting me take an action that would cure my disease because it would forfeit an organ that happens to be capable of doing something I’ve never desired it to do.

In Give It Up, I explore the abuses, negligence and scrutiny women and AFAB people face as they attempt to exert autonomy and access healthcare – two things that should be able to coexist.

You’ve painted close friends, Jamila Main, Caitlin Stasey, and many others in your works. What do you look for in a subject?

I look for subjects who have experience and can relate to the story I’m telling. I have no requirements when it comes to aesthetics, it's more about finding people who will be able to take direction and feel safe and comfortable shooting under the specific conditions needed to achieve the image I envision. Typically, this means they need to be comfortable with nudity, posing in various positions and at peace with me choosing to work with an image that might not be their particular favourite and trusting the vision. I have naturally gravitated towards working with actors because they come to the shoot with a professional attitude; they understand that time costs money, they’re practiced at performance and working with a camera and can draw on the emotions needed to convey a story.

What’s it like having your work exhibited in a solo show overseas in Singapore?

It’s very exhilarating and it comes with the added perk of travelling! I think, as it’s my first international solo, one of the most exciting aspects of it is that you get to experience a sort of anonymity. They haven’t bore witness to your entire evolution as an artist. You get to just drop in like a rockstar with a strong body of work all the years it has taken to get to that place of making confident work are cancelled from this audience and so opinions will be formed based on this body of work alone. It’s a wonderful opportunity to significantly broaden my audience.

Conversely, that lack of context can make the experience feel quite nerve wracking. After dedicating years to building an established style and message that has become known in Australia, showing internationally has the effect of making you feel like a beginner again and the insecurities do creep in. I’m extremely grateful to have my work platformed and supported in this way and so grateful to have been able to meet local Singaporean artists with whom I’ve only been able to connect with online until now.

What does your day-to-day look like? Do you have any studio rituals?

I like to take things slow if I possibly can. I drive to a cafe near my studio every morning, sip on a coffee or two and knock out my admin work. I try to avoid having menial tasks hanging over my head when I’m painting because I find that inhibits my creativity.

When I get to the studio, I like to make myself a tea, clean up and organise things a little bit, burn some incense and then put on a tv show or documentary that I can dip in and out of whilst I paint. I tend to turn my phone on silent and intentionally lose it somewhere in the studio so I don’t get caught up in doom scrolling.

Privacy is precious to me and I don't allow any visitors to my studio unless there is a professional appointment/meeting. I have worked almost every single day in my career years leading up to now, but I’m hoping this year will see some more balance.

Who is an artist you admire and why?

Oh, it’s so hard to choose just one! Sarah Sitkin’s 2018 series of bodysuits is something that did come to my mind as I was contemplating how humans relate to their bodies. In general, I’m typically drawn to works that are tactile, political, sculptural. I am drawn to the work of those who explore similar themes to me but who interpret their findings in other mediums. It fascinates me to discover differences in thinking and processing.

You exist at many different intersections, how do these perspectives shape your work, or influence the way you paint and create?

My ideas are typically born out of processing a personal lived experience and then I widen the lens to investigate the greater community’s shared experiences in an attempt to ascertain the scale and broader impact of the issue at hand. All of my work has been focused on disability and by extension, bodies and policy. I’m yet to put gender identity under a microscope in my work and I’m not sure if I will. I think there is a huge representation of gender diverse people within the disability community because those who face disability are forced to look at their relationship with their bodies and really dive into an investigation as to what their body represents to them and how they connect with it. So, I think the two subjects are linked and the discussion comes into my works implicitly.

How do you know when a painting is finished?

I feel that an artwork communicates what it needs to me in a way. For the entire process, the work demands some action from me. I deem a painting complete when I can’t feel it talking to me anymore and I suppose this usually happens when there’s a pleasing balance and harmony. It’s very instinctive – I have no set formula.

What’s next for you in 2023?

Off the back of two enormous years of intense deadlines and production, in 2023 I look forward to a short period of recollection and reflection. I am focussing some time on exploring new media and diversifying my practice a little bit, though painting is my first love and will remain predominant. I am looking to establish practices that will afford me some flexibility in future projects. I will be entering a few prizes this year – I have an incredible sitter lined up for the Archibald. I’m not ruling out exhibiting in the upcoming year in some capacity, but I firmly believe that time dedicated to development, experimentation and immersing oneself in life experiences is essential for artistic growth.

Give It Up is currently open at Yavuz Gallery, Singapore until October 20, 2022.