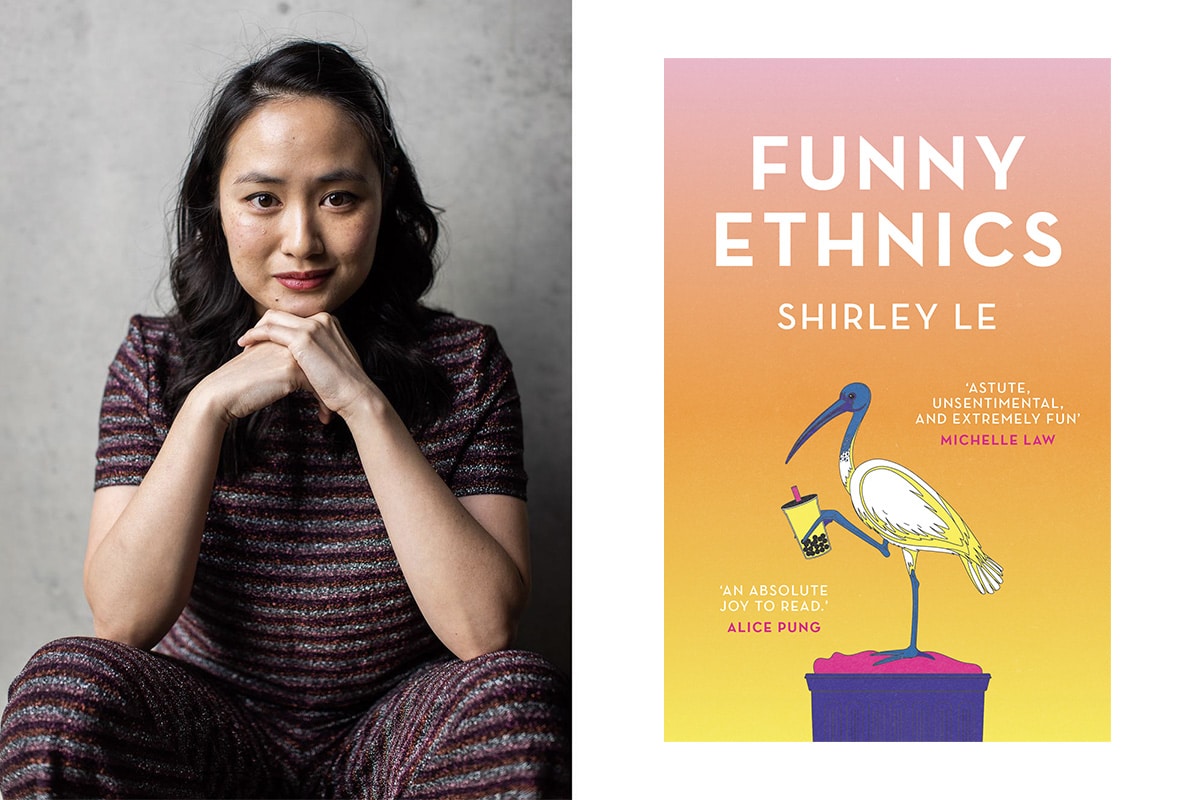

To complete her debut novel, Shirley Le found herself rewatching old episodes of The Simple Life and Laguna Beach. As such, discerning readers will find nuggets of dialogue from the defining noughties TV shows throughout Funny Ethnics.

For Le, tuning into both series was crucial in building the precise tone that existed in Western Sydney during the early 2000s. For context, her protagonist Sylvia Nguyen is a Vietnamese-Australian teenager coming of age in the decade after Pauline Hanson's ascent into politics. The media views her as one of many "automaton Asians"; Bà and Mẹ are withholding judgement until their daughter passes the selective school placement test. As far as Sylvia's concerned, she imagines herself as "a nit on a blonde scalp" – just one of countless sharp and droll observations that make the book worthwhile.

Funny Ethnics is the result of "a decade's worth of thinking", Le tells RUSSH. A mentorship Le received back in 2018 between Sweatshop Literacy Movement and Affirm Press helped accelerate the process.

Sylvia doesn't defy the odds not does she fail spectacularly. Her character is teeth-grindingly passive, stuck in a tug of war between what she wants and the desires ascribed to her by others. Given this, and the suffocating expectations of her parents and society at large, can you really blame her? Le has created a character not totally unwilling, but unable to meet the prerequisites of the model minority, by doing so exposing the inconsistencies and absurdity of them to begin with.

Below, Shirley Le speaks to RUSSH about finally facing herself on the page, writing as an act of community and what her dad had to say about Funny Ethnics.

Can you tell me about how Funny Ethnics came about? I read that you've been working on it for almost a decade.

A decade's worth of thinking time has gone into the book. But the process of piecing together chapters, the final sprint of that journey happened last year. Last year I got my shit together.

The thing about writing a coming of age book is you have to come of age first. I need the emotional distance to process certain things and then turn it into literature. That's how I work as a writer. Without that kind of distance, it's not going to be literature for me, it will just be a journal entry. I think for part of those 10 years I wasn't ready to face myself on the page either. So last year I got my act together, created a routine for myself and practiced the kind of self-discipline needed to take on such a huge project.

What did that routine look like for you?

Honestly, it's the simple things; taking care of yourself. If I'm going to write the next day, I need to be sleeping enough the night before. A big challenge I found while writing the book was self-doubt. I continually had to ask myself if this was a story worth telling. It was a huge mental obstacle. I also had to cut out the limiting self-talk.

What is it about Sylvia's world and her story that's missing from Australian literature?

As a second generation Vietnamese-Australian, I thought my place in Australian literature centred around a limited perspective of the Vietnamese experience: the war, the boat and the trauma. Because the stories about being Vietnamese were always about that, I was so focused on what I wasn't that I couldn't really see who I was as a person existing between the hyphen of Vietnamese and Australian.

When you don't see those experiences articulated, you start to doubt whether there's even a place for them.

Writing is painted as a solitary act, but for me writing is an act of engaging with your community. When I engaged with fellow second generation Vietnamese-Australians, I found that there was a yearning for our perspective to be included in the diaspora's growing body of literature.

Sure, there's mention of Sylvia's curiosity about the journey and experiences of her parents, but there's an opacity there. She'll never fully understand the first generation experience. I think that's part of the emotional truth of what being a second generation person is. You don't fully grasp what your elders went through, but whatever you do grasp you bring forward into your own life.

I enjoyed the snippets of Vietnamese throughout Funny Ethnics and how you didn't include translations or explanations. What was the thought process behind that?

Literature is a play on language and I really wanted to play with both languages.

Even though the bits of Vietnamese in Funny Ethnics aren't translated, I still like to believe that non-Vietnamese readers can infer what they mean from the rest of the sentence or paragraph. I think there is a playfulness as well. I'm having a private dialogue with readers who understand Vietnamese, but also for non-Vietnamese readers whatever meaning they infer from those Vietnamese bits will form their understanding of the story.

Food has a big role in Funny Ethnics and it's a source of shame for myriad reasons, not just its relationship to culture. Can you speak on that a little bit for me?

Sylvia's tumultuous relationship with food mirrors her tumultuous relationship with herself. She carries a shame of not feeling empowered enough to pursue what she really wants in life, and so food becomes either a reward or a punishment.

Being a person of colour, sometimes we feel like food is one of the few currencies that we have to be accepted. You eat my food, you consume my culture, right? Well in Funny Ethnics, food is something that connects Sylvia to her family at the dinner table, but it is actually something that can divide her and isolate her from her community too in terms of her disordered eating. I wanted to challenge the notions of food as a connecting force, food as an exotic currency to be offered up to a white gaze.

It also plays into the very specific issues that Southeast Asian women can experience when it comes to accepting our bodies as they are, because representations of Asian female beauty has centred on Kpop-influenced images. Asian women on the global stage as extremely thin, slender, and very pale skinned.

It also meshes well with the early noughties period Funny Ethnics is set in...

I really believe the early noughties was a misogynistic time. It was not a great time to be a woman. As a Vietnamese-Australian woman, I felt excluded from both worlds of popular culture. Not only the popular culture in Southeast Asia but the western world too.

I love how you've captured the unique voice of Western Sydney as well.

From a literary point of view, I've always been drawn to strong voices so this was intentional. In Western Sydney, having a smart mouth is one of the best weapons. I also think the area has so many great creative people, we shouldn't have to adopt other voices to be seen as intelligent, insightful, and observant. By reclaiming that voice that has been traditionally seen as trashy and unintelligent by wider Australia, I wanted to show how we can say really profound things but in simple ways that cut to the bone.

Funny Ethnics picks apart the model minority and rallies against that expectation. Was this heavy in your mind when you were writing the book?

The model minority is a concept that's been at the forefront of my mind for that last 10 years. In the 90s, I saw a completely different representation of Vietnamese-Australians and Asian Australians. It went from Vietnamese people being painted as drug-dealing criminals from Cabramatta to Pauline Hanson's line about us swamping the nation and being a threat. Then the early 2000s arrived and in white Australian media the focus shifted onto how Asian Australians were performing academically. Asian Australian children were viewed as compliant, silent overachievers but ultimately soulless.

I remember reading news articles about selective school results written in a racialized way and thinking that there was a human experience to this story that was missing. There was never room for nuance and complexity. Seeing that narrative shift made me realise that it doesn't matter whether the stereotype is negative or positive, it's still dehumanising.

Also, this stereotype that Asian Australians belong to this acceptable minority within Australian society is actually very toxic. It is used as a wedge to divide marginalised communities. So I wanted to shatter that in a book like Funny Ethnics, and I wanted to show that actually, there is solidarity between marginalised communities.

What has the response been like. Have people reached out to let you know they saw themselves in Funny Ethnics?

I've received quite a few messages on social media from fellow second generation Vietnamese-Australians, especially young women. It's blown my mind hearing from these people who could relate to Sylvia. There are also people from the community who have reached out and said they didn't go through those experiences, but were interested to hear about them.

I think representation, for me, is not about one voice or a few voices speaking for an entire community. It's about speaking from this community, not for this community. My role is to create a dialogue so that people within my community can talk more openly about certain issues.

I like the way you've put that.

If we want to talk about the elder generation's response, my parents have read Funny Ethnics. It was a whole experience. I would visit them every week and see my book move across different parts of the house. So it'd be near my father's computer. The next week it would be in the kitchen. It was absolute torture. Until the day came when my dad was like "oh, I've finished your book – by the way, that fragile table you speak of is actually 40 million years old, because that's how long it would take for fossils to form. So that's geologically a little bit inaccurate." So that's the only comment he had for me. It's hilarious.

See Shirley Le speak at Sydney Writers Festival for Coming of Age, a panel with fellow authors Kate Scott, Diana Reid, and journalist Melanie Kembrey.

Image: @annakucera.au