Long before Peter Beard discovered his Africa in the summer of 1955, it was living inside him. With news today of the iconic photographer’s passing, we’re celebrating his enduring connection to the land, and his documentation of a wild world that only exists in memory.

The image-maker and adventurer who discovered Iman had a childhood that reads like an American classic, with Beard seizing adventure with a boyish exuberance that would not dissipate with youth but instead go on to facilitate his life’s works.

“Home” between the years of 1945 and 1952 was on the 9th floor 133 E. 80th Street, NYC. “Good for throwing wet bum wad hand grenades at passers-by, watching firetrucks siren by,” he told us in an interview in 2015, on the 50th anniversary of his wildlife photography epic, The End Of the Game.

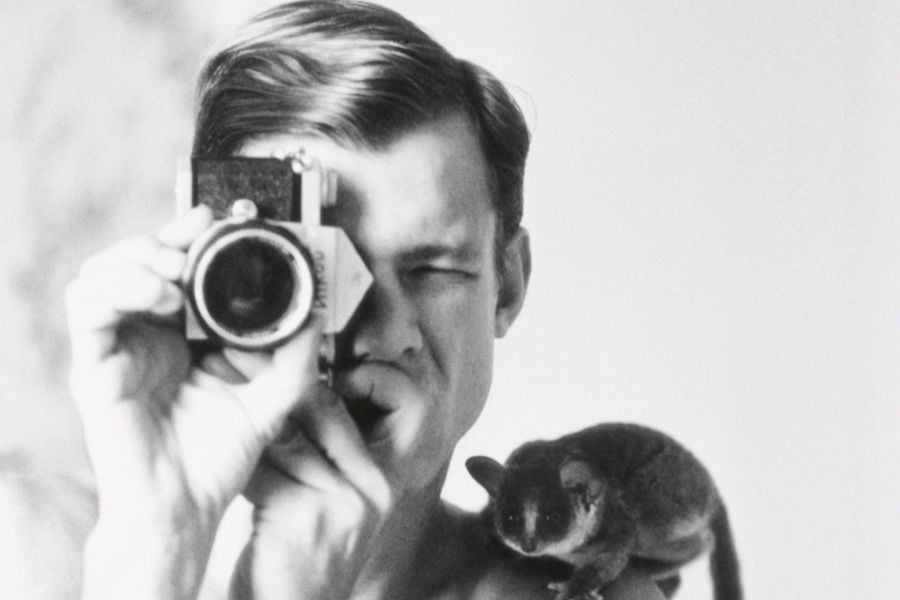

It was during those sunny, sepia-toned days of childhood that Beard unwittingly began building his legacy, recording his surroundings with the photographs – taken on a Voigtlander camera given to him by his grandmother - and the diaries, populated horse-hair clippings, animal skin, pebbles, bark, insects, bone, mud, and his most enduring medium, blood, not unlike those he collated later in life.

View this post on Instagram

But the year that set Beard’s life on course was his 17th - 1955. Of course,“1955 was Africa.”

“From Cape Town to Basutoland, Hluhluwe and iMfolozi, Bechuanaland, Mozambique, Gorongosa lions and elephants… then, for National Geographic magazine, more Madagascar, untouched forests and beaches, Aepyornis eggshells to dig up (extinct birds with eggs 16 times larger than ostrich eggs); then on the east coast the ‘retournement des morts’ (digging up their ancestor’s bones to re-shroud and re-bury them with honey and gifts). Huge cemeteries bearing wood-carved statues. Finding Langaha nasuta arboreal snakes; one snake was snuck back to the Bronx Zoo - the first one they had ever seen.”

By 2015, he said, with the melancholy that regularly punctuated his descriptions of natural beauty loved and lost, “those giant forests of Madagascar are eaten away and the only lemurs left are hunted for food.”

Inevitably, Beard returned to the USA where, following his graduation from Pomfret School in Connecticut, he enrolled at Yale as a pre-medical student, where a class in population dynamics sparked his interest in the exponential growth of the human population, before he switched to art history and began working as a photographer for Conde Naste. Soon, though, Africa would call him home.

View this post on Instagram

Beard found his soul connection in Kenya, in the lands of his friend Karen Blixen’s Out of Africa. Like Blixen, he’d “caught the rhythm of Africa”, and it was no coincidence that he would go on to acquire land adjoining that which once belonged to the author “at the foot of the Ngong Hills”, a property known as Hog Ranch.

Beard continued to commute between Kenya and the urban jungle of New York, and later Montauk, where he ran with the Studio 54 set - Mick and Bianca Jagger, Bacon, Dalí and Warhol himself - many of whom would be photographed, diarised, immortalised in his works.

View this post on Instagram

It was testament to Beard’s magnetism that many of his high-society friends, from the Kennedys to the Duponts, would follow him back to Hog Ranch, bringing his seemingly disparate worlds together at once. And then there were the muses - among them Lauren Hutton, Janice Dickinson, Verushka (whom Beard photographed with a roped rhino during a relocation programme) and Iman (who he famously discovered in Nairobi before helping to launch her modelling career in New York).

It was during Beard’s early days in Kenya, spent working in Tsavo East National Park, that he began compiling photo evidence of the environmental destruction creeping upon those idyllic surrounds, and, ultimately, the death of more than 35 000 elephants. These works would culminate in the first edition of The End of the Game: The Last Word from Paradise; not the last, but perhaps the most iconic and admired of Beard’s published works.

Beard approached the fate of planet earth with only slightly more softness than he, a self-described fatalist, regarded his own existence. “Rest assured it is the seemingly unstoppable human race racing into evermore war-ridden, ever more poisoned, poor old global spaceship earth, adjusting to centuries of misinterpretation and rude and ugly behaviour,” he told us. Yet, despite his scepticism, along with many threats over the years to leave Kenya behind, through multiple controversies, marriages, a near-fatal encounter with an elephant and all else that comes with a life lived to its limits, Africa remained a constant for much of Beard’s.

View this post on Instagram

Beard campaigned for the protection of the environment into his later years. And in capturing the last vestiges of his place of connection, Beard has in some way contributed to its preservation, though not in a traditional sense, and, one would assume, not in the way he wished. By default, too, as one of the last great photographers of another time - he contributed to our visual recall of those wild years of hedonism and innocence, of history's foremost personalities escaped to the wilderness.

If he is right about the world's fate, then the sweet, fertile depths of memory may be a small salvation: a not quite alternative to true preservation. If there ever was a reason for photography, then surely this is it.

“What is home to me?” - he answered the question, back then, with a rhetorical one. “Well, it’s on the run. Deep in the wastelands of Kenya’s Northern Frontier District and Tsavo – 8,300 square miles of dead elephants, far out camps, giant scorpions all over the place.

View this post on Instagram

“The outback – that’s what far-off Madagascar and then Lake Rudolph meant for me for six years – (110-120°F) sand, desert, huge lake, snakes, crocs; and the most authentic of all Kenya tribes, veritable shag-bags, scarifications on all sides, insane machine-gun sentences, ivory through the nose, everything. And everything else seems trivial.”

With a life lived in the public eye and on his terms, with no shortage of controversy, Beard was skeptical of the media. But in the case of our interview five years ago, he had just one condition - that he sign off with “beam me up, Scotty.”

With confirmation that the photographer has passed into the next dimension at age 82, we like to think of him in the Africa of his wildest dreams.

Excerpts taken from an interview with Peter Beard for RUSSH Issue 65. The re-edition of Peter Beard, by Peter and Nejma Beard, is coming soon to Taschen.