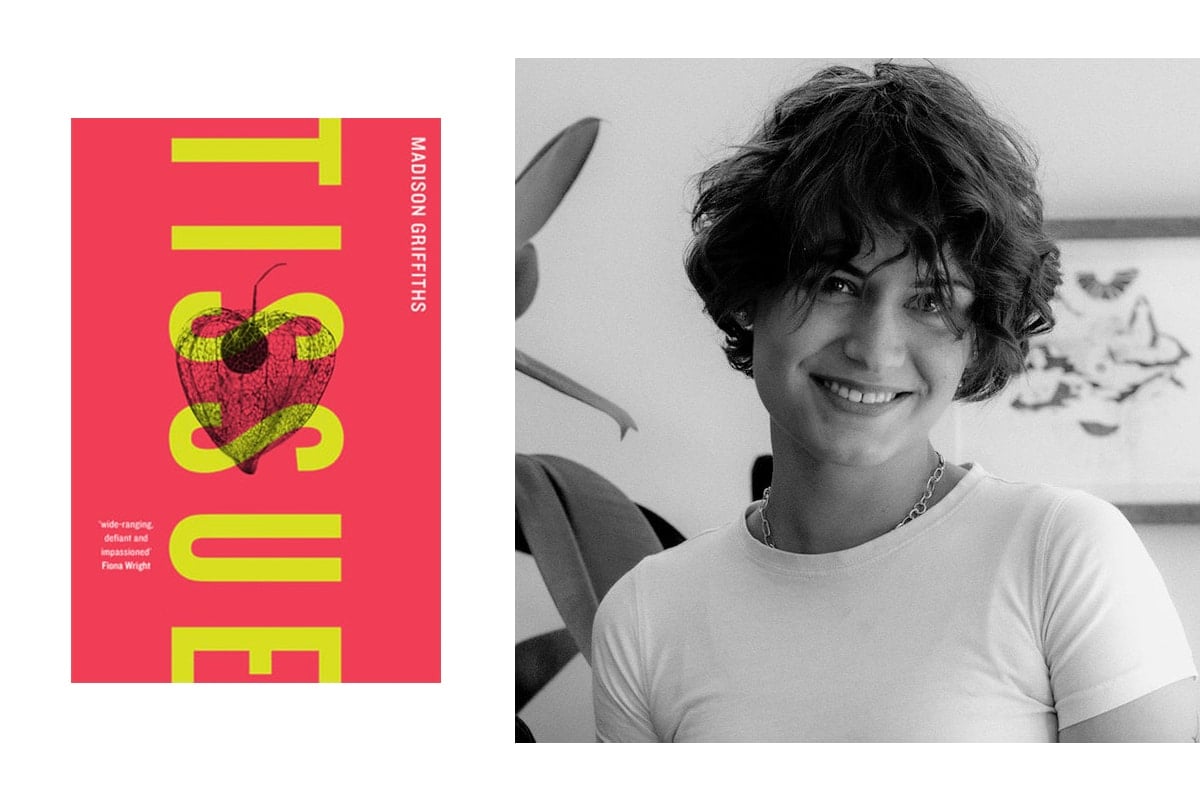

When Madison Griffiths was 21, she penned an essay titled An Open Letter to My Vagina. Safe to say, the tattoo artist and Tissue author is unflinching when it comes to matters of the body. Her debut book, which unravels our social and political relationship to abortion, exists as further proof. In fact, Griffiths tells RUSSH that when we remove the taboo, we'll find that "the body just wants to speak".

Ahead of her appearance at Sydney Opera House for All About Women, we caught up with Griffiths over Zoom where we bonding over criminally bad internet, the urge to cut our hair short, and how treacherous working from home can be (suddenly we're all deep cleaning the bathroom). We also got stuck into the subject at the heart of her panel: Our Bodies.

Below, Griffiths opens up about the most significant tattoo she's given and received, how her Scottish Deerhound reminds her of the body's rules, and the first time she was made to feel like her body wasn't her own. The author also shares two book recommendations, citing her love of writers whose work she can feel. Find our conversation, below.

The panel you're participating in is interested in the body and all the different ways it relates to each speaker’s area of expertise. But I was wondering with you, when was the first time you were made to feel like your body wasn’t your own?

That's a brilliant question. For me particularly – and I'd say this is shared by a lot of women – that entry into adolescence is when you're starting to notice gender as something tangible. I think there was a particular moment between year seven and year nine where sex and the body becomes messy and muddied. Your body's changing whether you want it to or not.

There was a real hierarchy and discourse even about little things like who got their period first and what that meant. I think those conversations were always deeply intriguing to me. Particularly because I did go through puberty quite young. By the time I was in year nine, I was 14 galavanting around with “a woman's body”. How that rubbed up against the world in terms of how I felt about my body in regards to sex and how it was being viewed really shifted at that point.

Is there an example that sticks out to you?

When I was 16 I cut my hair really short for the first time. That was a real moment for me because I didn't realise that women could have short hair until I saw a girl at my school, who's two years above me, walking around with a pixie cut. It absolutely stopped me in my tracks. So when I cut my hair for the first time at 16, it was this real play with the costume of gender and the costume of the body.

Sinead O’Connor, Emma Watson – there are these cultural moments of short hair reclamation. I think what's interesting about when a woman arrives at that moment – I mean this is very binary speaking – you sort of have to question why it feels so free to have shorter hair. There's something deeply symbolic in that, that I'm just curious about and always have been.

With your book Tissue you talk about your own experience of abortion. In some of your essays too you discuss tattoos and bodily autonomy from your own perspective. What’s behind the choice to frame these conversations around your own experiences? Do you find it difficult to be publicly vulnerable in this way?

It's a very deliberate thing that I do. I always wanted to create a character out of myself that accurately showed the way in which I rubbed up against the world. Not necessarily in its defence – I'm really careful not to defend my actions per se. I don't want to be dogmatic. I don't want to seem like an expert. I want to appear as someone who is not necessarily judgmental, but curious about how one's own body experiences the world at large.

I think a lot of truths can be found in the places where we’re told not to look. Particularly for women, we've long been politically ostracised to the home, to the domestic sphere. But what happens if I add a scholarly lens to the bedroom? What happens if I look at pillow talk in that particular way to give it a discursive edge? Because I think that there's a lot of truths in how we occupy our bodies that have long been taken for granted or not been seen as something worth looking at intimately and cheekily as well. I like taking the piss out of myself because it's easy to do. And I think that's when you can get to the heart of what you're trying to say.

Can you talk about the process of writing Tissue?

I wanted to write Tissue in a short time frame. I wanted to feel the urgency of what it would be like to write a book within the legal parameters of acquiring an abortion; to try and capture the entirety of that liminal experience within the allocated time frame that people are afforded. I wanted to feel that tension. So because of the urgent deadline, that meant I was writing in the evenings after work.

And when you're writing a book from the comfort of your bed at 2am, the character that you're speaking to is the woman that's awake in those hours. So the experiences that I translated into Tissue was a version of me that existed in this one space and I packed the more boring or more daytime elements of my personality aside, because it didn't feel like that was where the stigma lived.

It’s interesting, listening to your description reminds me of how actors have to psych themselves into the right frame of mind to perform a scene.

You can really get lost in it. As a creative nonfiction writer, I sometimes need people to pull me out of it.

But once you decide that the body isn’t taboo, once you decide that – and the first article I ever published at 21 was titled An Open Letter to My Vagina – then the world’s your oyster.

If the body’s off limits, then what happens when the body is on limits? The body just wants to speak.

I saw that you’re working on another project, can you talk about it yet?

It's abstract at the moment but I want to look at power imbalances in relationships, particularly how those evolve in pedagogical contexts. So how those evolve in university spaces; spaces that are rich with “agency”. You know, you're stepping into a space, you're 18 or 19 and you think you're pretty top shit. How do you go into that space and navigate the power imbalances when it comes to love and sex that famously happens a lot on campus. Look at Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir.

That’s going to be a lot more research-based in the sense that I’m interviewing a lot of different people. So it will be less rooted in my own experiences.

On the subject of your tattoo work, what’s the most significant tattoo you’ve given and received?

That’s a huge question. The most significant tattoo I’ve gotten is this tiny little Venus symbol. It’s very old-school feminist iconography. I was in Sweden, I would’ve just turned 21, and I was in a really shitty relationship at the time. The person I was with was in Europe, hence why I was there, and I had made friends with these two Swedes a couple of years prior – they were these hilarious, gorgeous girls that were on their gap year in Australia. So when I went to Sweden, I hit them up; I told them everything. You know, “I'm in a terrible relationship. I don't know what to do.”

I only had one tattoo at the time and so we went and got this Venus tattoo. There was something about having that wound and nursing it. When I went back to my abusive partner, I left within a 10-day to two-week period from getting that tattoo. And while that tattoo was being nursed, I was made aware of the other wounds that I was navigating. So it felt very, I don't want to say spiritual because that's not necessarily how it felt, but it felt serendipitous. It felt like I could see how the body ought to respond to a wound.

I think also when I tattooed myself for the first time, it was a nice moment because there's a metaphor in the fact that I went in way too deep. I didn't really understand that you don't need to stab yourself to leave a mark. And I had to learn how to be more gentle with myself in order to then be appropriately equipped to tattoo others.

In terms of the most significant tattoo I've given, last week I tattooed the word “tissue” onto someone which was wild. That felt incredibly special and this person was so generous with their body, it was their first tattoo.

But I think zooming out, in terms of a genre of tattoos that I find particularly empowering, I have a huge queer clientele and there are a lot of slurs that have been reclaimed in the queer community over the last however many years. There's something incredibly exciting about tattooing a “slur” onto somebody who in the gesture to wound themselves with something that has been historically used against them as a weapon, it’s so transgressive. I think it's so inherently queer. It's reclamatory in its essence, it says “this is the wound that exists and it's mine now, and it's going to move and grow with me”. Wiping the excess blood away from that wound and leaving it polished is such a privilege to be able to do.

Can you recommend a book that’s informed how you see the world?

Maggie Nelson’s book The Argonauts is sensational, especially the way Nelson looks to the body and isn’t afraid to dismantle the hierarchies we have about what experiences matter.

Deborah Levy’s Hot Milk too. There’s something so sexy about that text which I love. I think she plays with queerness and displacement beautifully. I love writers whose work I can feel.

Is there something you do everyday that helps you connect with your body?

There’s something about my daily walks with my dog, a Scottish Deerhound named Phil, that are very meditative. I have a very embarrassing demeanour with my dog; I'm loud and expressive and if he's digging a hole in the sand, I'm there digging a hole in the sand with him.

He really grounds me, particularly because there’s a deep irony in the fact that when I'm writing about the body, I can often forget about my own bodily needs. I can forget to eat or when to go to sleep or when to snap out of it. Whereas an animal is honest, and he knows when it's time to go for a walk and he has his timeline. So being able to honour that is being able to just honour the rules of the body that we should listen to.

This is a broad one. But is there something you think people still get wrong about the body?

The political discussions about who is a woman and therefore what makes a woman’s body are a deliberate transphobic distraction from the truths of the unique experiences of the body. When I started writing about my body, it wasn’t to tell the truth of all women’s bodies or to decide that all women must have some lived experience shared with me. It was so that all women are forced in their own ways to grapple with their body, regardless of whether it looks or functions in the same way as someone else’s.

I think that hurdle to overcome politically is stopping incredibly rich conversations from being had across the gender spectrum about the body itself and the truths it can tell when it’s not put under a microscope.

So if we're more politically primed to allow people of all genders to engage with body politics, the literacy of the body will really go somewhere because in that lives curiosity and empathy. I'm excited for those kinds of conversations to hopefully begin dwindling away so we can make more space for the truth of the body across the board.

It was something that I was really careful of when I decided to write a book on abortion. I was cognizant of it because these debates do live in the reproductive access space and it was deeply necessary for me to invite trans people into that conversation. Because many trans people experience abortion.

You've said in the past that you're drawn to the “big wound of misogyny”. What's occupying your thoughts recently?

You've asked me this at a wonderful time. In the last three months, I've become incredibly jaded. You can see I've dyed my hair red; I’m in my villainous era. But one thing I've discovered about misogyny that I find quite intriguing is that men are so willing and able to offer themselves the full scope of humanness. Particularly in the research that I've been doing regarding pedagogical relationships.

It is very easy for a man, particularly a man of power, to assume that the truths of his, say, sexual attraction or the truths of his interest in women are sacred to him. It's just part of what makes him a human. And when you zoom out, and you look at the way women aren't afforded the ability to be forgiven so much in their sexual proclivities or even in their relationship to their own sexuality, I do find that entitlement to desire interesting. So entitlement to desire is the new frontier I'm wanting to interrogate when it comes to misogyny, for sure.

You said you go through these periods of being jaded. Does this inhibit your work or do you just accept it and roll with it?

I accept it and roll with it. But I have to hold myself accountable to it in the work. So one thing I try to do is when I feel that coming on, I poke fun at it in the writing style. I will try to allude to the fact that I might be a little judgmental right now. That isn't particularly good for the project. But what is good for the project is the reader's access into me grappling with that judgement. It's being honest and documenting that is important to me. If I tried to make it unbiased, I would be lying to myself as well. I think there is great value in the ability to view this as a woman too. I think it's a more generous way to write, because for me, I'm wanting to open the door. I offer my experiences up as anecdotes for people to think about the things they may have forgotten about themselves.

You can listen to Madison Griffiths in conversation with Tanya Hosch, Grace Tame, and Tara Rae Moss in the 'Our Bodies' panel moderated by Jamila Rizvi on Sunday, March 10. 'Our Bodies' will take place at Sydney Opera House as part of All About Women.