Luke Mayes is modest about his South Pigalle apartment in Paris’s 9th arrondissement. “It’s essentially a rather beautiful dive,” describes the in-house photographer for designer Rick Owens jokingly. The space, which he shares with his partner Jeanne and their three-year-old son Ryder, has been home to the trio since 2016; they moved in shortly after Ryder was born. “The market in Paris is notoriously difficult, but I think this place was hard for them to find tenants for, for the exact reasons we liked it,” he says. “It was kind of falling apart. Everything was untouched, they’d left all the original floorboards and tiles, despite many of them being broken. The kitchen had nothing but a sink. It was basically there for us to do whatever we wanted with it.”

Born and raised in Adelaide, Mayes relocated to Paris in 2010, where an interest in photography and fashion eventually lead to the position working alongside Owens (he currently also oversees graphics, social media, and any image-based content the brand produces, such as books and films). “I’ve always loved the work photographers like Marina Faust and Ronald Stoops did with Margiela, or Max Vadukul with Yohji [Yamomato], the in-house documentation for those brands (among others) was beautiful. I wouldn’t compare myself to them, but having the chance to work with Rick and document something that has historical and cultural significance is incredibly rewarding,” he explains. “There’s only a handful of us working directly with Rick [Jeanne included], so to collaborate so closely with someone who’s had such a huge impact on the industry, and design in general, has been an immense privilege.”

“The area has grown on us and is close to everything. Although, it’s disconcerting looking around at the young hipster professionals with strollers on the weekend and the realisation sets in that you’ve become one of them.”

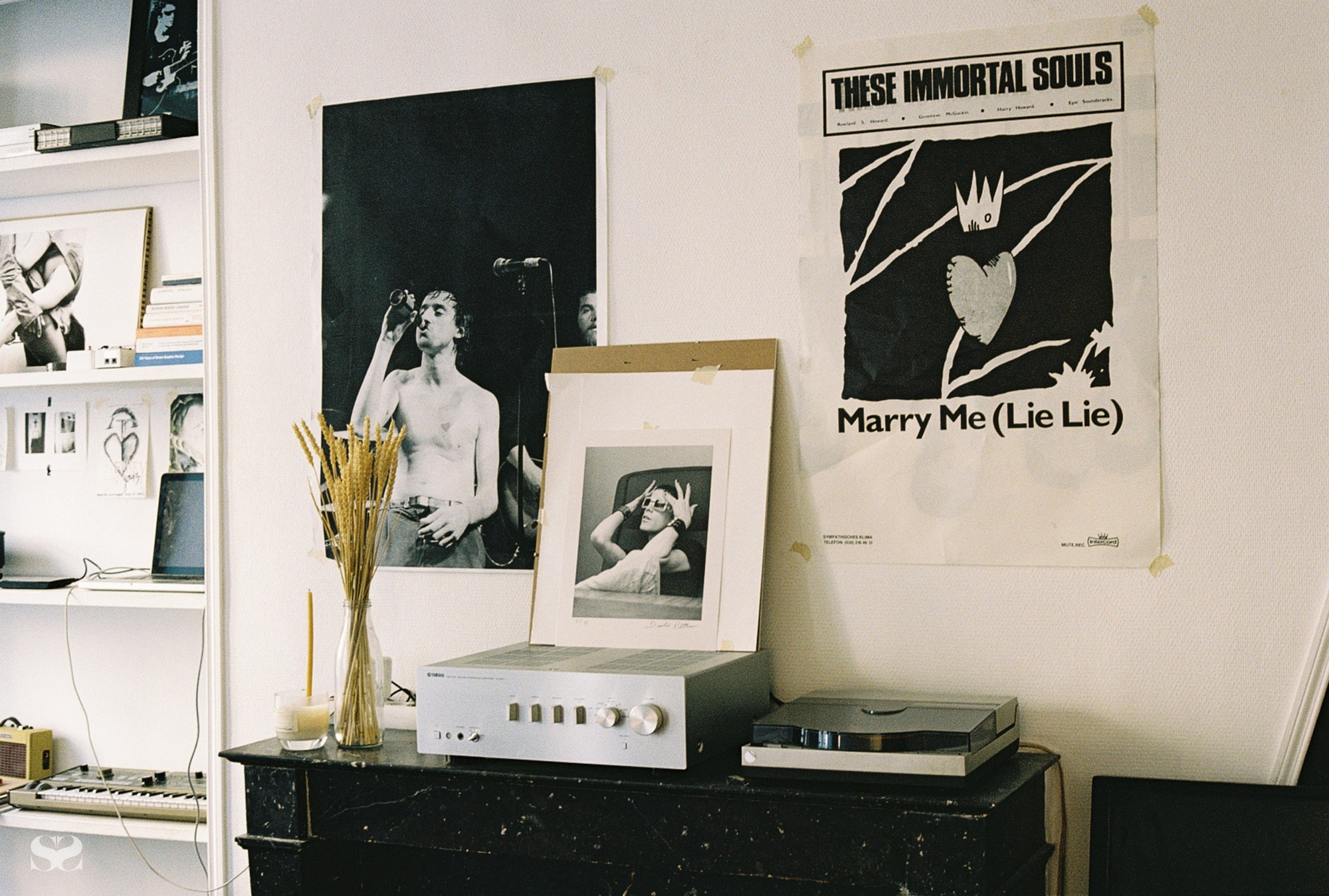

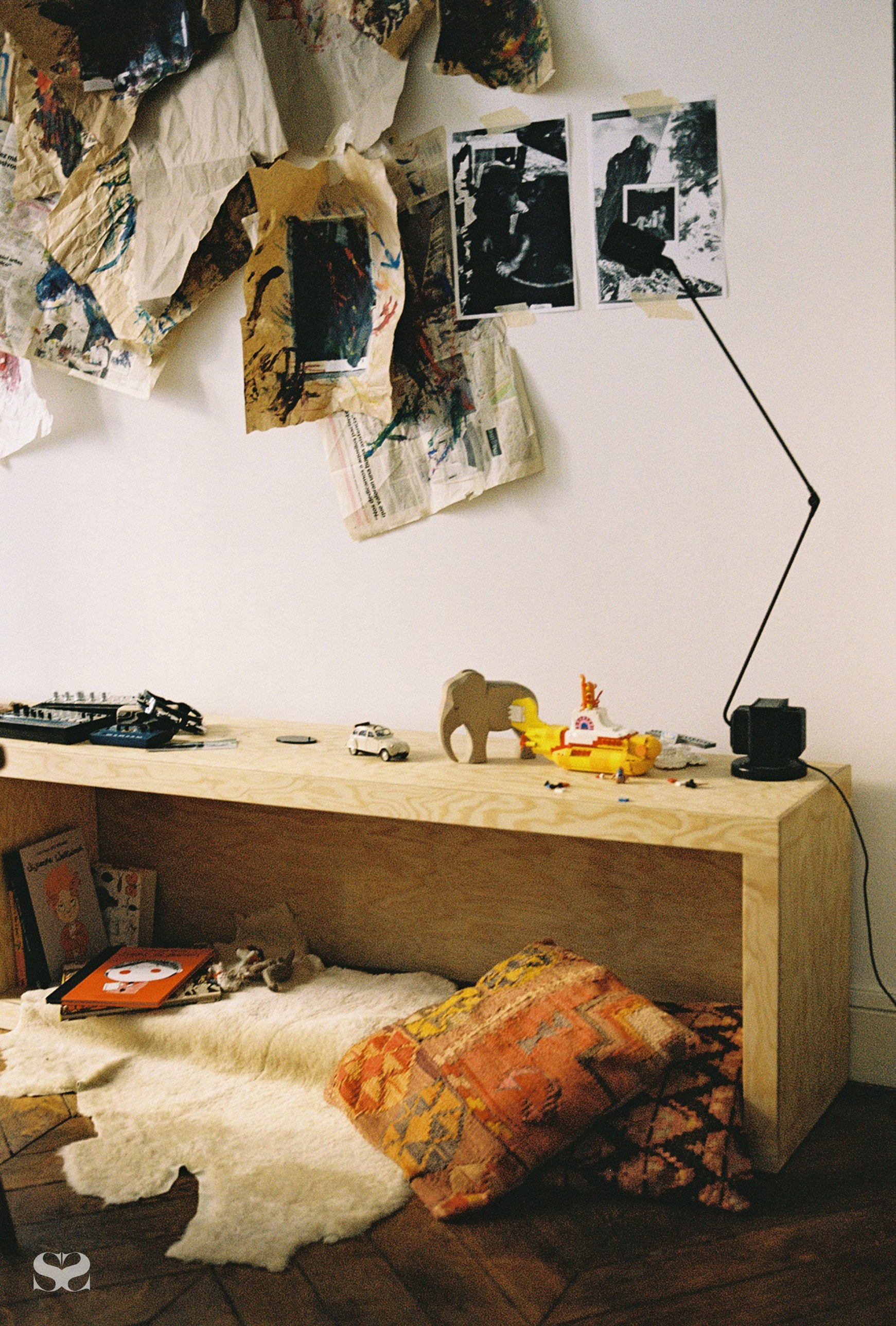

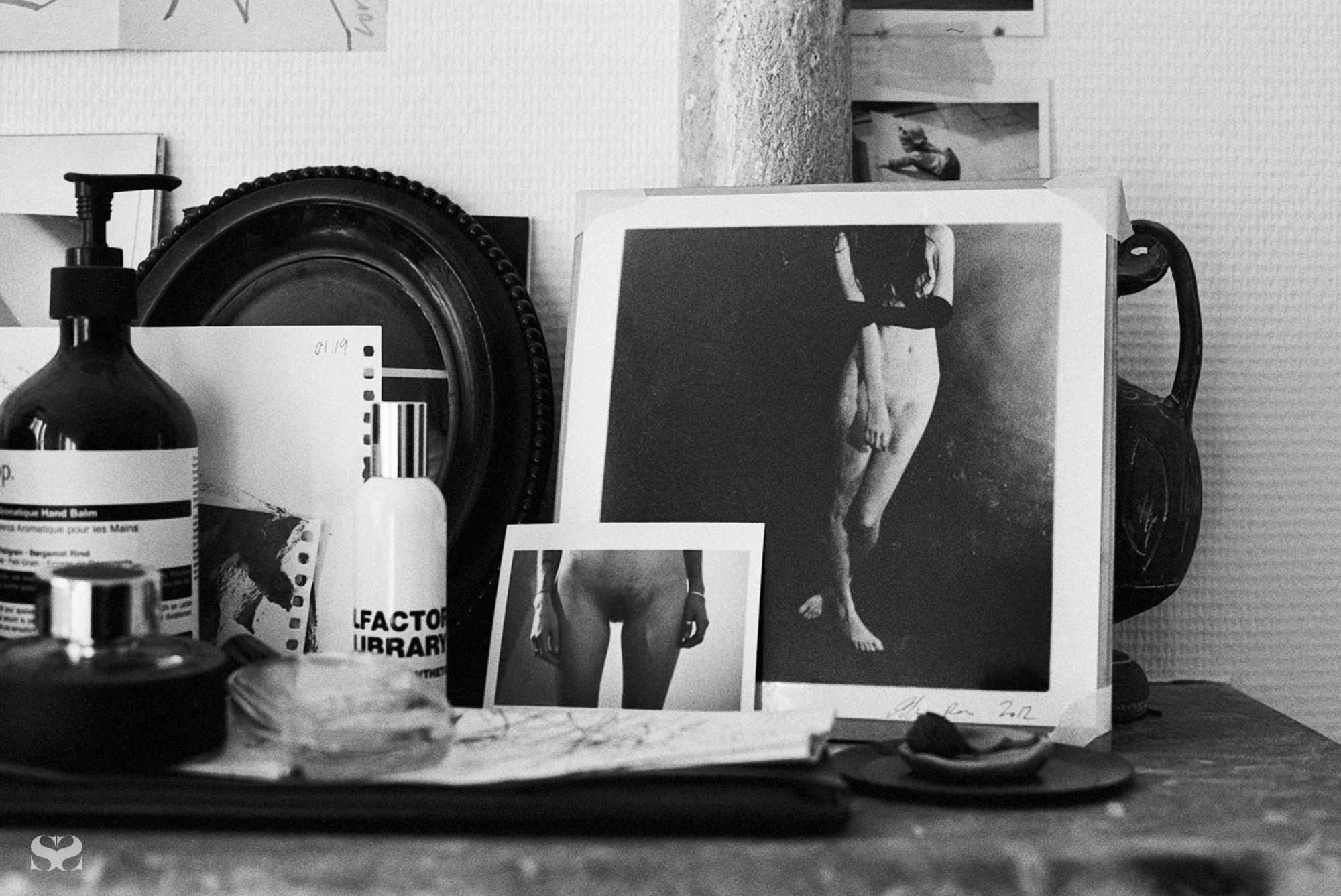

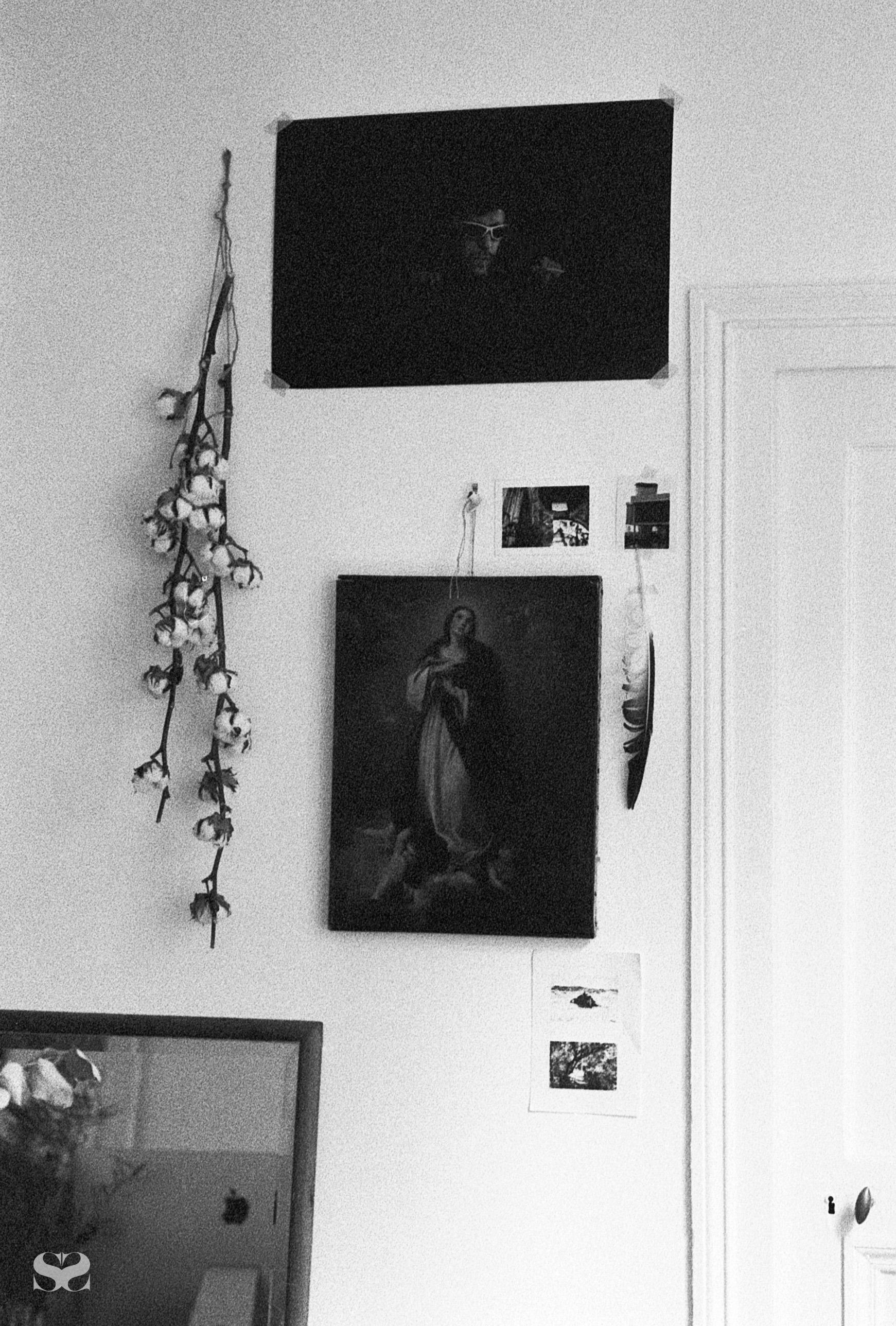

As with most creative professionals, work has a habit of following Mayes home – on any given day you might find his captures printed and stuck on the walls of the apartment (“when I’m trying to work out if it’s any good or not”), beside an original 1970s poster for a Cy Twombly exhibition at Yvon Lambert, and stills by director and photographer Larry Clark. There are many other vignettes throughout the house, artworks painted by Ryder are patched together instinctually with Jeanne’s drawings and sketches, and watercolours from her mother. “[It] isn’t overly thought out,” Mayes explains of the various shrines. “They’re all just taped up as we go, often over the top of each other.”

Music is another formative influence for Mayes, and when he’s not producing for Owens he spends his time documenting for South London band Fat White Family. “We’ve been following them for years and I try shoot them as much as I can. Anyone yet to hear them should drop whatever they’re doing and buy their records.” Mayes himself played in various bands when he was still living in Australia, “I played guitar but since Ryder was born I’ve started keeping more instruments around, especially synthesisers and drum machines, anything easier or more engaging for children,” he explains. “It’s motivated me to start playing more.”

Mayes and Jeanne’s vast collection of fashion and photography books can also be found throughout the space, many stacked upon the bookshelf made for them by Owens. It’s one of the various pieces in the house crafted by the designer, with other treasured items including the plywood half box chair in the apartment’s entrance, and a bronze alchemy chair, vases, bowls and ashtrays.

Another favourite is a recently procured 1960s Georg Thams leather sofa. “Thams is not as collectable as some of the other mid-century Danish designers, but there’s something about this sofa I love. The arm rests resemble a sports car of that period, like a Lamborghini Miura or something.”

Mayes is a fan of mid-century influence, citing French designers Jean Prouvé, Charlotte Perriand, Pierre Jeanneret and Le Corbusier as favourites. “There’s a gallery in L.A. – Galerie Half – which I quite like. They mix [those] designers with mid-century Danish, old farmhouse furniture, and various European antiques – it’s got a lot more warmth,” he describes. “I like the idea of seeing this stuff in some old decaying palazzo, everything patched up with scotch tape. That’s closer to what I’m aiming for.” Beyond the couples’ eye for art and design, it’s this feeling of being lived-in that gives Mayes’s home its character – an energy that permeates throughout, suggesting that many have lived and loved within this space. “I’m attracted to things that show traces of use over time, and furniture, industrial design, and interiors seem to be one of the most appealing and idealistic examples of that,” he says. “It’s still quite some way off getting to where we want it, we have pieces and improvements in mind that we’re working towards, but it’s coming along slowly.”

“I have a huge list of pieces I’d like, but how it all comes together is not really planned. In general, you can always find a way to make good design, good pieces, go together.”

One gets the feeling that Mayes’s home will never be completely ‘finished’ – there will always be fresh sketches to be taped on walls, new work to contemplate, music to listen to and books to display. Which is perhaps the beauty of it all; it is a home that lives as ardently as its occupants.

See more inside the 'Place To Be' issue of RUSSH Magazine.