Artist Julian Meagher is a romantic. It's evident through his turn of phrase, through the muted palette that shapes his canvas paintings, through his practice as a creator of beautiful, evocative large-scale works. "I think most artists I know apply their pursuit of beauty and truth to most aspects of their life," he tells me in the lead up to his new solo exhibition, The Space Into Bicheno, opening September 18 at Sydney's Olsen Gallery. "I think it’s harder to compartmentalise that, it’s such a formative part of your personality; whether you’re cooking, or whether it applies to love or relationships, or friendships ... you’re searching for truth a lot of the time. And you don’t have a boss, you don’t have anyone telling you what to do. And so there is a freedom, that’s one of the nice things about what we do, is that freedom to pursue truth. I think that most of the time it's quite romantic in a way."

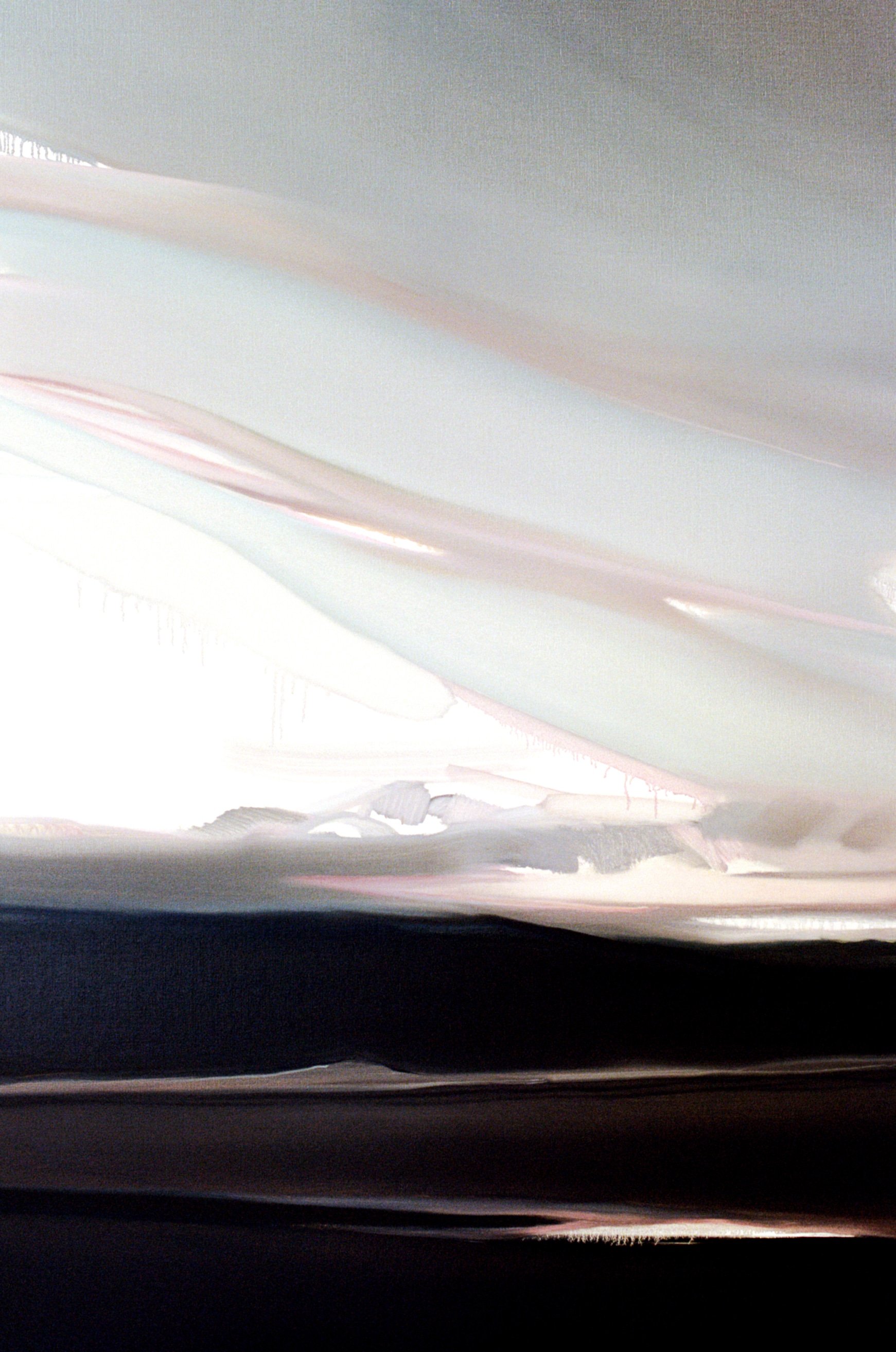

Painted from the east coast of Tasmania, The Space Into Bicheno is a product of Meagher's exploration into his relationship to country, as much a series of self-portraits as they are portrayals of tender, haunting vistas. "[I] always shied away from painting the Australian landscape, struggled with my place in its tradition as a white painter. A friend once said that beauty is the sharpest tool in the box, I guess this has guided me at times on this series."

To celebrate the launch of his new exhibition, we talk to Meagher about fatherhood, the moon and why it's just as important to celebrate life's losses.

"I wanted the work to talk to everything, big things at least, and nod to the huge transition becoming a father has had on my view on things. Especially me."

On his upbringing ...

I was born in Sydney, and I’m one of six children, from a big tribe. So the house was always very busy, and I think a large part of me is still chasing moments of calmness. My mum was a very good artist, so I grew up always being surrounded by a studio, stuff like that - there was a studio for her and a studio for the kids. So art’s always been in our family, it’s been a language we’ve all spoken since I was a kid pretty much ...

On his creative education ...

I’m probably the only [sibling] that’s stupid enough to try and make a living out of it ... I studied for a bit over in Florence in my early 20s. I went to an art school there and learnt the very traditional techniques, which ... even though I’m painting very differently now, it’s still the basis of a lot of where my practice has originated from. And over the years I have developed my own technique. I think that time was really critical for me to sort of learn a lot about transparent paint, and how to manoeuvre oil paint around it. I think that study was a really important time for me.

"It’s funny how something you can do so many years ago still informs your practice now."

On the moon ...

This moon has crept into this series. My son’s middle name, Darsh, means ‘first sign of the moon’ in Sanskrit. His first word was moon, and he would often point it out to me even when he was 10-months-old and couldn’t speak. I found myself looking at the moon and thinking about it even when he wasn’t around, seeing things differently. Thinking about the way the moon influences everything but so so quietly; water, tides, plants, reproduction of most species, and things that we will ever know ... The word for moon in my wife’s language Gujarati is ‘Chandra Mama’. It is used as a symbolic representation of reverence and respect for nature.

On opening The Space Into Bicheno ...

I think I’m much better off just focusing on trying to make good paintings. And then after that I have to just try and step back from it all. But I’m getting better at enjoying the other side of things; showing the work, and beginning to feel a little bit happier with it ... There’s moments in every artist’s day when you think you’re a genius, or you think you’re just kidding yourself. I kind of oscillate between the two extremes and it can do your head in. So I kind of, I’m sitting pretty well with this one ... I’m so much better at making paintings than standing in front of it, let’s put it that way.

On self-criticism ...

The eternal pursuit of the perfect painting ... you’re never going to get it, that’s why you start another one. I’ve just got a lot better accepting it. That comes with the territory of making stuff. Get used to it - that’s the journey and don’t complain about it, because there’s beautiful moments in it as well. And you have your wins, and you have your losses … and that’s the game. And there’s nothing wrong with losing. I think so much of our life is always about the wins, and the beautiful moments in time, but it’s the bad moments and the bad paintings that make everything good as well. I’ve got so much better at accepting the fact that some days things ain’t gonna go well. I think having a baby was really good for that for me, to remind me that I’m not really in control of anything, and I’ve let go a lot, and that’s actually helped me make better paintings, by sort of you know, letting go of the control of the outcome of them.

"They’re a nice entry point into thinking about Australia and our landscape and identity and time, and where we’re going and where we’ve been, and our place in that whole journey really."