When I was pregnant with my son I found out he was breech at 34 weeks. The term ‘breech’ simply meaning a baby is set on landing in the world like an Olympic gymnast: head high, feet planted – perfect for a gymnast, not ideal for a baby attempting to make its way safely down a birth canal. In a modern hospital, delivering a breech baby naturally is seen as a near impossibility, an obstetrician’s answer to the problem being a planned C-section. As a first (and possibly last) time mum, I was determined to have my shot at birthing naturally so I promptly began researching every tried and tested way to turn a baby in utero, ranging from the scientifically proven to the slightly more experimental.

In my investigation I came across an Australian documentary called The Face of Birth, which delved into approaches to pregnancy and birth among Australia's First Nations peoples and included the unique perspectives of two exceptionally experienced Aboriginal midwives.

Sisters Lena and Rosie Pula from the Arlparra Urapuntja community in Central Australia stood out to me for one specific reason: in 50 years of practice they had never had to deliver a breech baby. Not because they hadn’t encountered the situation (about 5 per cent of babies are breech at full term, so it’s not entirely uncommon), but because they knew exactly what to do to guide babies in all sorts of problematic positions along the smoothest, safest and quickest possible route earthward. “Head down, make baby straight. They can come out quick,” says Lena matter of factly, as if it were the easiest thing in the world.

First off, a little confronting for me was that for all of my exploration of alternative medicine over the years I knew very little of the ancient traditions founded and practised in my own place of birth by the oldest living cultural group in the world. I can claim to have some degree of knowledge on everything from Ayurveda to Chinese medicine, Native American shamanic healing and Western herbal medicine, but of the ‘bush medicine’ described by Lena in the film I was woefully ignorant. But what struck me most about it was that for a problem Western medicine couldn’t seem to solve without surgery, these Indigenous midwives had a simple, non-invasive solution that apparently boasted a 100 per cent success rate. I realised that I had a lot to catch up on, and potentially a lot to gain from learning the ways of some of the most resilient people on earth.

Prior to European settlement and the introduction of hospitals, surgical procedures and drugs, traditional Aboriginal healers had been responsible for the healthcare of communities for thousands of years. Before the arrival of deadly foreign diseases like smallpox, typhoid and influenza, their system of medicine ensured the survival and prosperity of the Aboriginal people longer than any other in the history of mankind.

Within this system, disease prevention was key, something a properly prepared, naturally organic, seasonal diet and active lifestyle largely took care of. But, like all fallible humans, there were times of both mental and physical crisis, and for these Indigenous Australians turned to community healers who used a range of treatments, including sacred rituals and plant medicines, to cure a host of ills.

Like many of the Eastern philosophies that have made their way into the Western wellness vernacular, Indigenous Australian healing techniques take a far more holistic approach to the treatment of illness and disease than allopathic medicine as we know it.

Mind, body and spirit are seen as interconnected, and equally significant, aspects of an indivisible whole, with the greatest influence being that of ‘spirit’. While it’s important not to paint all Aboriginal culture with one broad stroke – there are hundreds of different clans and nations, each with their unique customs, traditions and world view – the spiritual dimension to physical illness is a common fundamental belief. Whether it be an intangible malaise originating from within the individual or a malevolent outside force, the spiritual aspect of illness must be addressed before healing can occur.

In a rare book on the subject, published by the Ngaanyatjarra Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Women’s Council Aboriginal Corporation and titled Traditional Healers of Central Australia: Ngangkari, many of these ancient practices are detailed by the Ngangkari practitioners themselves, who are working hard to keep the art and science of traditional healing alive. One of these respected healers, the late Andy Tjilari, is quoted in its pages, describing how the healing spirit, or ‘mapanpa’, is a crucial tool for the healer. “Ngangkari use their own mapanpa to do their healing treatments … the mapanpa live inside parts of the Ngangkari’s bodies, such as the palm of the hand. Sometimes the hands feel as if they had been speared by the power of the mapanpa.”

Similarly, a group of women healers belonging to the Yolngu people of northeast Arnhem Land work with the power of spirit to practise and preserve their ancient healing traditions for the benefit of future generations. Ali Azzopardi was embraced into the kinship of the Yolngu people seven years ago and now works as coordinator and project manager for the healers. “The healing women of northeast Arnhem Land that I work with very closely are ‘the Seven Sisters’, known in their spiritually significant culture as Djulpan,” she tells me. “They have the hidden knowledge for healing and for the Manikay or crying ceremony, ‘the Crying’ – a very powerful healing cry only the significant elders and knowledge keepers can sing.

“In this cry, we cry for the Land and in this cry we bring healing for the Land which in turn brings healing to us and our people.”

Connection to the land and the natural world is of deep significance to the healers and many of their rituals and treatments involve working closely with nature to achieve a state of wellbeing and repair. One of the senior healers with whom Azzopardi works closely is a woman by the name of Djerrknu (Eunice) Marika, who describes for me some of the ways in which a Yolngu healer might use natural elements to treat a variety of afflictions. “Our medicines all come from the bush that surrounds us,” she says. “We use the gunga [pandanus], healing through weaving. Laluk and rakay [pandanus nut and reeds], bucharinganing [a healing leaf that when boiled releases a therapeutic oil], hot healing rocks, gurtha [fire] … All the medicine we need comes from our Land. We have medicine for eyes, boils, backache, toothache – special leaves for smoking ceremony to heal grief and bring clearing and clarity, cleansing and healing mind, body and spirit.

“As one we move and work together, us women of Arnhem Land, together to heal the people, black or white.”

According to Marika the bush medicines are highly effective in treating both mental and physical illness, from depression to broken bones. “We can heal everything,” she says. “We have a lore as healing women to stop the period pain using giri giri [gadayka bark – stringy bark]. We get the bark off the tree, then pound and crush it, put in water and boil it in the fire. After boiling it becomes red and we cool it, and then when it feels cool we put it in a cup and drink it like a cup of tea,” she explains. “We use leaves from the bush called bucharinganing to heal all aches and pains in the body and awaken the spirit. We have traditional bush saunas; using rakay [water reeds], rangan [paperbark sheaths], laluk [pandanus nuts] and bucharinganing we create a bush sauna that can heal terminal illnesses, especially bringing healing, very special healing, to the sick person’s spirit and physical pain.

“This healing comes from a woman’s heart. The joy and happiness and healing comes out of their heart.”

Marika also emphasises the importance of sacred bush foods in the prevention and treatment of illness, like rakay [the water chestnut], and yukuwa [yams], which are considered an ancient superfood for energy and vitality, and mineral-rich seafood such as oysters, mussels and mud crabs.

Permeating all this knowledge is a sense of ‘oneness’, of being inextricably connected, to the land, to spirit and to community. In the absence of that connection, of working together for a common good, the individual suffers. What impacts one, impacts all. “In all Indigenous cultures and traditions in Australia we work together as a family,” says Marika. “Sisters all working together with our granddaughters, who are learning from the old people, the knowledge keepers. We heal together. Our heads and our minds and our hands work together. This is the Yolngu way.”

By drawing on the power of nature and collective intention, healers like the Djulpan women of Arnhem Land and the Ngangkari of Central Australia have been known to achieve results that leave Western medicine at a loss for explanation. Results that we, with our limited frame of reference, might call miracles. Azzopardi describes watching as the Yolngu healers placed a patient with cancer in a traditional bush sauna, wrapped completely in paperbark, in a bed of steaming plants for two hours. “I watched this lady get covered in wet reeds, paperbark, bucharinganing, pandanus nut, fire, warmth and steam rising to cradle her and heal her for hours, with beautiful Yolngu women healers pressing their hands and leaves into her, to bring great healing to her physical pain and broken spirit. The transformation was phenomenal, as this lady rose from the bush sauna, healed.

“The Yolngu have a depth of knowledge and remarkable traditional healing practices, working so beautifully together, as one.”

To be clear, no one is suggesting that someone with an illness as serious as cancer should forgo conventional medical advice, but surely there is something to be gained by investigating these ancient practices and philosophies and potentially integrating them with modern medicine for the mutual benefit of both. This is something the women healers of the Yolngu are passionate advocates for and would like to see happen in our lifetime. “I think it’s very important to incorporate the two worlds together and have Yolngu and balanda (black people and white people) working very closely together. Both are important healers in this day and age. The ancient traditional Yolngu healing practice must not be lost, as it is so powerful and sacred, but it also now must work alongside Western medicine, as both have so much to offer,” says Azzopardi. “Yolngu have a healing practice and bush medicine for everything and wish to work closely alongside balanda. Not only does this empower Yolngu people, and keep the sacred knowledge of healing passed from one generation to another, but it also brings healing to a nation as a whole. It keeps Yolngu strong in their culture, keeping culture alive.”

The continuation of the healing lineage and the transference of knowledge is paramount to these Indigenous practitioners to ensure the ongoing health not only of their communities, but of all people and the land that supports all life.

Which is a huge reason why the healers believe that assisting and supporting new mothers and infants entering the world is essential – it’s where it all begins. “Yolngu people and healers wish to work alongside midwives,” says Marika. “Bringing important healing ceremonies to our newborn babies, to ensure that child walks the Land in a healthy way, connected to his kinship system. Yolngu also want to bring healing to the mother.”

In The Face of Birth, another respected elder, Kathy Mills, describes in further detail the special way in which the Aboriginal midwives guide a baby down the birth canal for the smoothest possible journey. “They sing the baby out,” she says. “They sing [to] the baby, which way to go. They feel and they guide that baby, because they know. They’ve been through that channel, they know every little turn and twist. So they tell that baby, it’s safe to come.” In a final attempt to budge my stubborn breech baby ahead of his impending due date, and in the absence of access to one of these magical midwives, I resorted to modern medicine’s decidedly more clinical means of coaxing a baby into the correct position for birth, unromantically called ‘external cephalic version’ (ECV). Lying on a hospital bed beneath fluorescent lighting, hooked up to heart monitors, injected with a drug that would supposedly make the whole thing easier, I felt nothing of the emotional or spiritual connection to the life inside me that these women had described. Instead I felt uncomfortable, agitated and racked with anxiety. After three unsuccessful attempts at encouraging my baby to perform a swan dive, my well-meaning doctor told it to me straight: “I’m sorry, he’s not going to turn. I won’t force it, it’s too risky.” My face must have worn my devastation like an approaching storm because when I pleaded for him to try again –“just one more time, you won’t need to force it”– he finally, reluctantly, agreed. This time I closed my eyes and thought of Lena and Rosie. I thought of the profound connection they shared with the natural world, with each other, and with the divine spirit they believe animates all life on earth, including that which has not yet been born into physical form. And so I began to sing, a gentle mantra of encouragement in my mind, to my unborn child. “Baby, I’ve been down this path. I know this road. It’s safe to come.” And on that final attempt, without any force, he turned and settled into a prime position for a grand entrance into the world.

Whatever term you choose – ‘spirit’, ‘higher mind’ or ‘subconscious’ – that abstract, intangible element invisible to most human eyes has been shown time and time again to significantly influence the healing process of the individual.

You need only research ‘the placebo effect’ to find hundreds of examples of this mysterious mind-body connection at play. What science is only beginning to understand on an intellectual level, Indigenous healers have known intuitively since time immemorial. “We know without white people what we’ve always known,” says Marika.

“Our grandmothers passed this on to us, and we too wish and need to pass our sacred knowledge and medicine onto them, our own granddaughters, our future generations.

“To keep our people and Yolngu culture strong. To heal the land, and all people.”

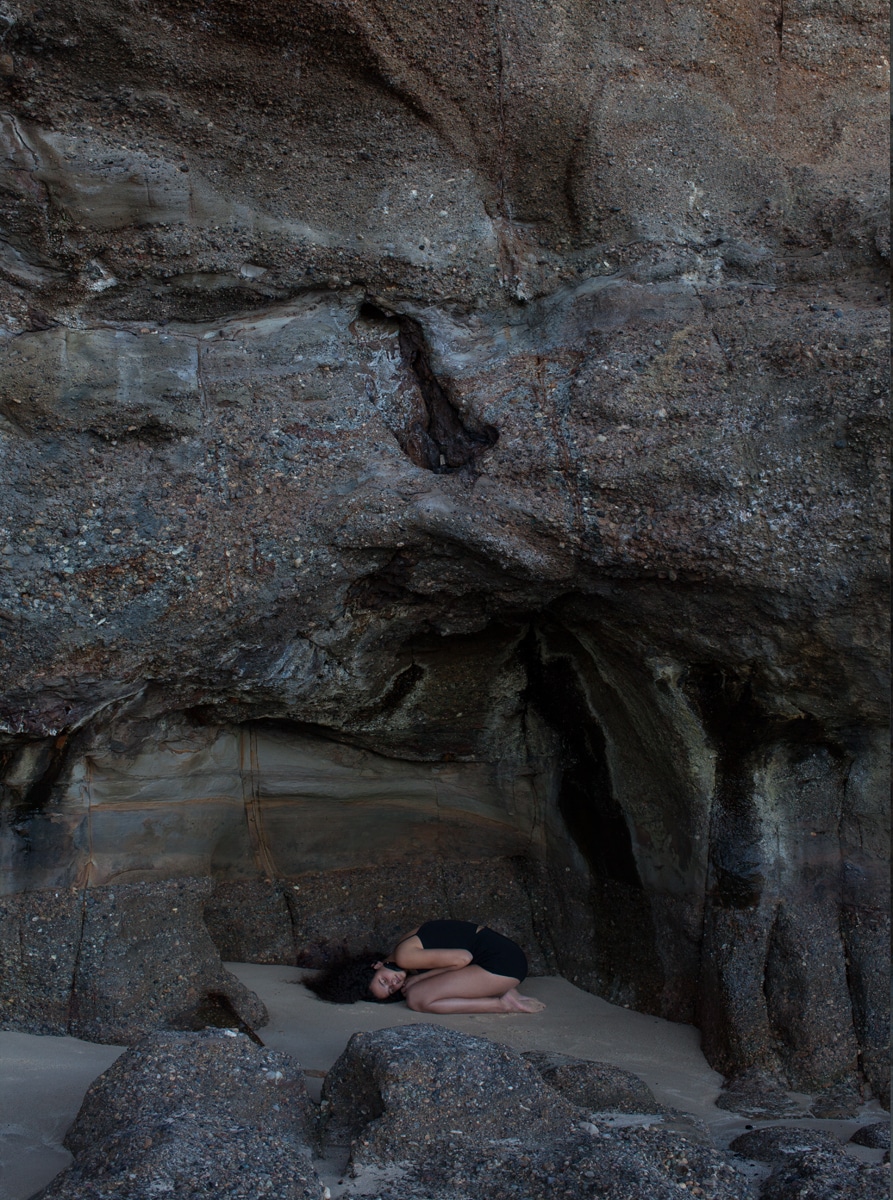

PHOTOGRAPHY Caroline Presbury

FASHION & BEAUTY Ellen Presbury

MODEL Sanne Jackson @ Kult Australia

HAIR Taylor James Redman using Hair Rituel by Sisley Paris