Dean Cross began his career as a dancer. Though the works of Albert Namatjira filled the childhood home of this artist raised on Ngunnawal / Ngambri Country, of Worimi descent, his full awakening to other disciplines came much later. With a housemate who happened to bring home some cheap canvases arrived the epiphany there was nothing to stop him from painting. “Something happened internally,” he says. “And I actually never recovered.” Nowadays Cross would never commit himself to the constraints of just one medium.

With creative idols including Tracey Moffatt, Cornelia Parker and Rachel Whiteread, Cross is a keen archivist, concerned with the context of our post colonial epoch. He’s also a romantic: “Who doesn’t love an old photo and being lost in the narrative?” he says.

When we speak, he is navigating the practicalities of creation in our isolation and planning a project that will see him recreate, then destroy, (Captain) Cook’s Cottage.

As an integral voice in the next generation of Australian artists – with the next generation of Australians front of mind – Cross’s statements are intended as part of a dialogue.

“I think, the worst sort of art is that where you look at it, it tells you everything about it ... To me that’s boring, that’s dead art. I think art, it’s like people ... The best people reveal themselves over time. They’re complicated ... And I think artwork should be the same.”

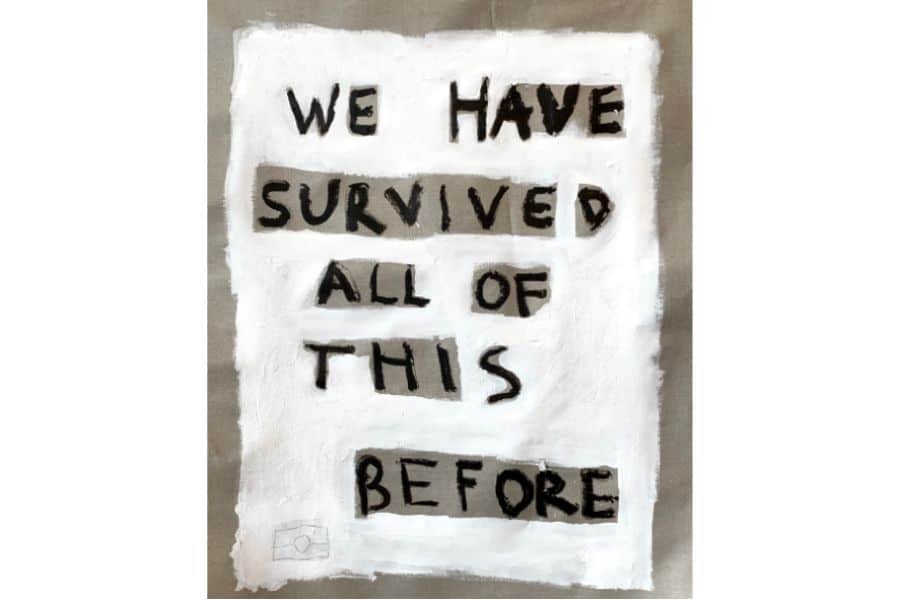

Dean Cross, 23rd March (1788-2020), oilstick and gesso on linen.

How have you found this time [of lockdown] in terms of inspiration? Is it flowing more or less?

It’s just different. I mean, I think it’s hard. I don’t want to fall into a trap of making boring art. I think we’ll see a lot of that in the next 18 months … There’s just going to be so much of it really, it’s going to be quite hilarious ... So I think it’s been a challenge just to temper that and still try and find some clarity in thinking and not to completely disengage with the things that I was interested in before all of this was happening. But, I mean, it comes and goes. [That’s] always the case though, coronavirus or not.

For the purpose of the interview, what are you interested in?

That’s a good question. I think broadly across my work, I try to keep it varied but I’m interested in power structures, I suppose, that are played out through narratives that we adhere to culturally and socially, and a questioning of their relevance. And whether or not those kind of power relationships are still serving their function, which usually they’re not.

With the kind of the postcolonial lens and all of us that share a post colonial structure that we live in, it’s an endless loop of, what would it be like if it was different?

But of course, it never can be different. I often will condense that down into dialogues, into landscape, into portraiture, into the way that those two things can collapse in Aboriginal culture. And the struggles, I think, between or in that.

In terms of your connection to your heritage, how has that been throughout your life?

Varied I guess. My grandfather, he was a violent man I guess you’d say, a product of the war. Well he was given to a white family when his mother died and that started this kind of journey and my old man really wanted nothing to do with him. You know, we never spoke about my grandfather. He died long before I was born but it was an absolute silence in our household. And then as my old man aged and softened so too did his feelings around his own family and with that came a kind of broadening, I guess, of familial engagement ... But I mean, we were always kind of engaged in community in Canberra.

You know, it was one of those funny things where as a kid, you don’t think about it ... It wasn’t until I got into high school. I remember – I think year eight maybe – these two girls in the class ... I must have been trying to be charming. And they said, ‘Oh, what’s in you?’ And that was the first time anybody had ever said that to me. I went to this kind of boujee high school. And I thought, I don’t even really understand what that means. But that was first time where I started, for myself as an individual, to think about the bigger picture that I was involved in; the narrative of my life, and what that meant. But of course, I deal with it a lot in my work. You know, I think it’s an unfortunate side effect of the colonial project ... There can be a narrow expectation around what it means to be Aboriginal. And I think that it’s important for people whose story doesn’t necessarily follow the same narrative to articulate that. If you’re not from the mission for example, or you’re not related to someone famous or something, there can be shame around that ...

As the years go by the whole landscape is going to change for young Aboriginal people. And I think that it’s important that they’re taught to feel confident and secure in knowing who they are and where they’re from, regardless of the context to those stories.

How did that dialogue, and analysis of that narrative, find its way into your art?

So my very first exhibition was the Redlands [Konica Minolta] Art Prize at the National Art School; the timing was falling around Anzac Day ... And I guess I’d started to think about the strange kind of dichotomy of the human body, my body with these multiple genetic histories. You know, one pathway of my family, you’ve got my Aboriginal family who was here struggling. And then the other part of my family, there were people fighting at Gallipoli and my great great grandfather is still buried there ... before he was there, he fought in the Boer war, he was a proper red coat colonial murderer. There are so many conflicting stories or complicated narratives within any individual’s life. How do you separate them? I’m not sure if you can. So I think that’s sort of when I started to really directly work or think about it, or materialise it I guess. Up until that point, it’d been an internal thing that I didn’t share with anybody.

In terms of being on country as a method of communication, can you tell me about that, or how that is for you?

Oh there’s nothing better. I would give anything to be at home. I guess I should explain too that like a lot of people like me who who didn’t grow up on ancestral Country, [I’m] sort of torn between two places. One is, where you grew up, where you spent all your time, where you were born, which is Ngunnawal / Ngambri Country and I have a very strong connection there. Undoubtedly. But then also when I go up north, Worimi Country ... to go up there and to walk along beaches that I know my ancestors walked on; to sit and touch a tree that I know they would’ve sat under ... There’s this place that my partner and I go to, and every time we go something unusual happens. Last time we went, this old dingo, she came and sat down right next to me and fell asleep for about two hours. Just out of the bush. This is true ... she was dreaming, twitching around as dogs do and at one point she woke up and looked at me and smiled and went back to sleep.

It’s those moments when you understand that you’re communicating.

That was my great grandmother coming to say hello, to sort of just sit there and be with you. And of course, no words are necessary for that type of communication. But the feeling is profound. There were times when tears were streaming down my face because it was such a profound meeting of souls.

Wow, that gave me ... I have goosebumps ... On the subject of communication, what do you feel are the biggest barriers to that for you as an artist, and a human?

Well, I think ... Other people. People will always bring their baggage to everything. Don’t they? Myself included. And so I think you’re always up against that initially. And you’re relying on a willingness in your viewer to go where you want them to go emotionally, conceptually, whatever, to be willing to take that leap and let their own baggage down. I think as a dancer ... I used to get so frustrated at dance audiences. Because they would always say, ‘I don’t get it.’ I’d say, ‘It’s not so much about ‘getting’ anything but what did you think?’ But they were always so afraid.

People are so afraid to sound stupid. They’re so scared that they’ll say the wrong thing. So they usually say nothing.

The little art world echo chamber is not so bad. But you can always tell too, though, when people don’t like what you’ve done, they’ll just say, ‘Oh, well done, that was beautiful.’ ... You get that a lot.

You’ve spoken in interviews about shifting perspectives ...

I think about that a lot; it’s about starting small. To get to our house on the farm you’ve got to go down this bloody long dirt road, you pass this beautiful old yellow box Scar Tree. I think the real moment of clarity I had around that was [when] I was working on this post-[Sidney] Nolan Kelly mythology, thinking about ... the role of public memorialisation. Thinking about, where are the Aboriginal monuments? ... Why don’t they exist? But then suddenly this tree that I’d passed thousands of times, it revealed itself. Of course, there they are. Country is the monument. Our survival is the monument. I mean, it’s always the same, isn’t it? It starts with the young people. But when you can teach young people that those seemingly insignificant marks on a tree, to an understanding eye, are actually profoundly significant then I think that – well, in my Utopian vision – will permeate more broadly.

I think to non Aboriginal people, [Country] is a word that they understand, intellectually, how it’s used.

But to really be able to articulate what Country is, what it feels like, is difficult. I mean, on some days, I think, actually, that’s all my work is about, is trying to articulate that.

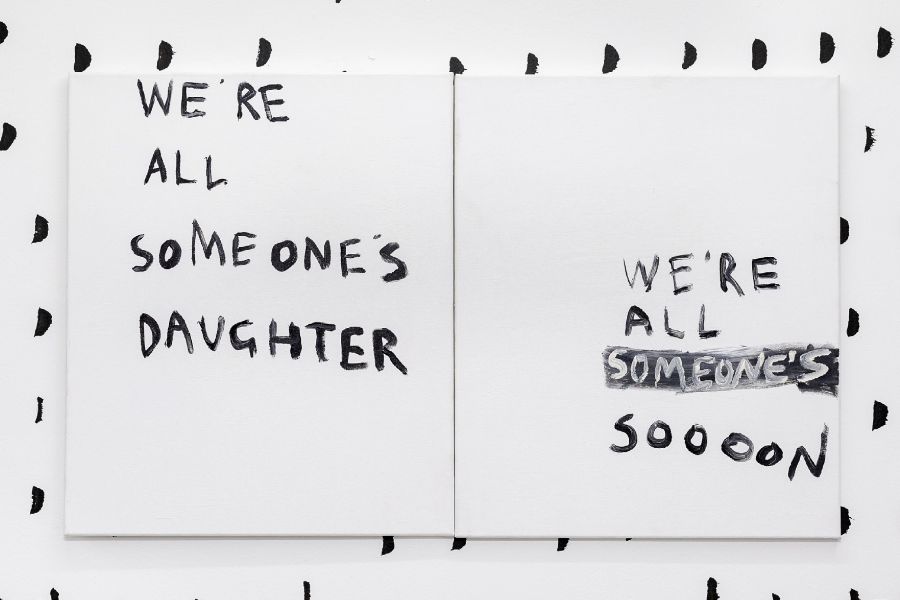

Dean Cross, Anthem, acrylic on canvas, 2018.

How would you describe it in words now?

Well, I don’t think it can be. That’s the thing. Country is the word. It’s like Dreaming, right? It’s a placeholder, but it almost feels impolite to try to reduce something as profound and beautiful as Country, as Dreaming, to English language. But I mean, maybe it’s like that feeling on a bright day when the sun feels good. Or like that rainy day when it feels good. I don’t know. I’m already trying to and I’m regretting it. But what I do know is that it’s palpable and it’s tactile ... There’s a point when I cross the river when I go up north that, from one side of the river’s not Country to the other side is. The same going home; there’s a slight dip in the Hume Highway, where there’s no discernible feature but the road just dips slightly across this small creek. And I know then that I’m home, that I’m on Country.

Read the complete interview with Dean Cross in our Connection issue, out now.

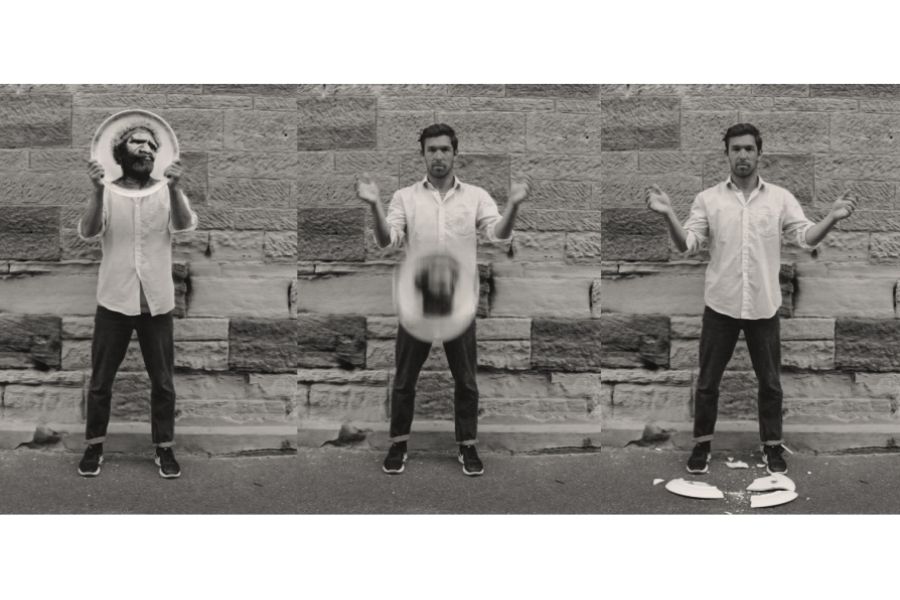

Feature image: Dean Cross, Dropping the Bullshit (we look like this too), 2016, pure pigment on BFK Rives.