There is an unmistakable bond between these two contemporary artists but Tony Albert sees Daniel Boyd as more than a heroic mentor. He’s his Yalandji Brother and a culture warrior; a part of an expanding field of artists who are working to create a more self-aware set of cultural relations. One that celebrates the nuance, potency and urgency of Indigenous practitioners and their histories.

The pair discuss Boyd’s current show at the Art Gallery of NSW, Treasure Island and how it holds a critical lens to colonial history, explores multiplicity within narratives, foregrounds Indigenous perspectives and interrogates blackness as a form of First Nations’ resistance. Along with something quite rare. His technique.

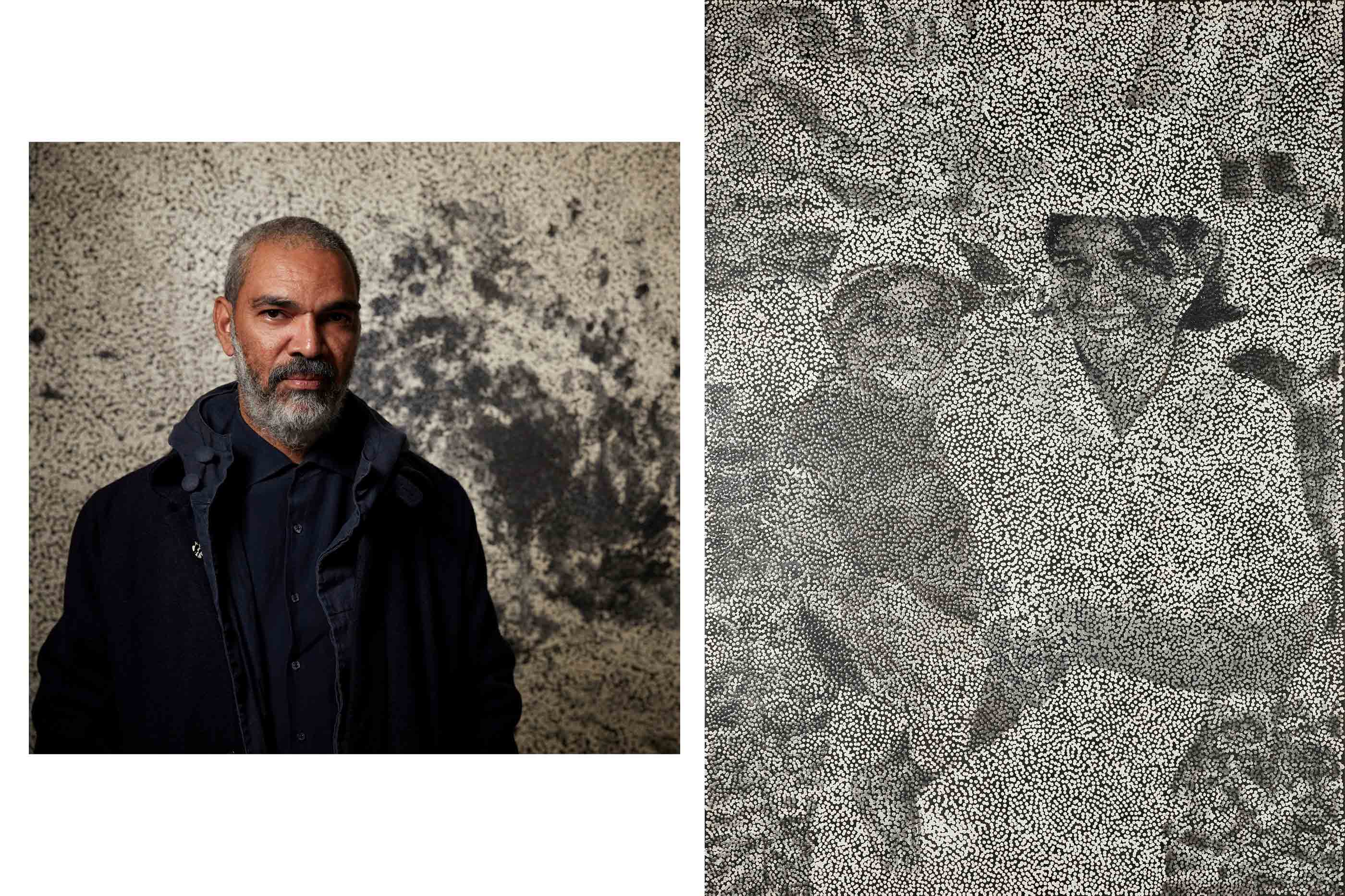

Daniel Boyd, 2022

Image: AGNSW, Jenni Carter

This is your first solo exhibition?

Yes, my first major solo show in an institution in Australia. It’s kind of nice to have this opportunity to be able to share so many works together as a group, because you never really get that opportunity to show this amount of works together. People have probably only seen maybe one or two of my works in institutions, but otherwise, there are my shows at commercial galleries or smaller institutions where they’ve been [in] groupings, where they kind of have a common thread or theme that ties them together. I’ve always known how the language operates as a whole. It’s just nice to share that with the public.

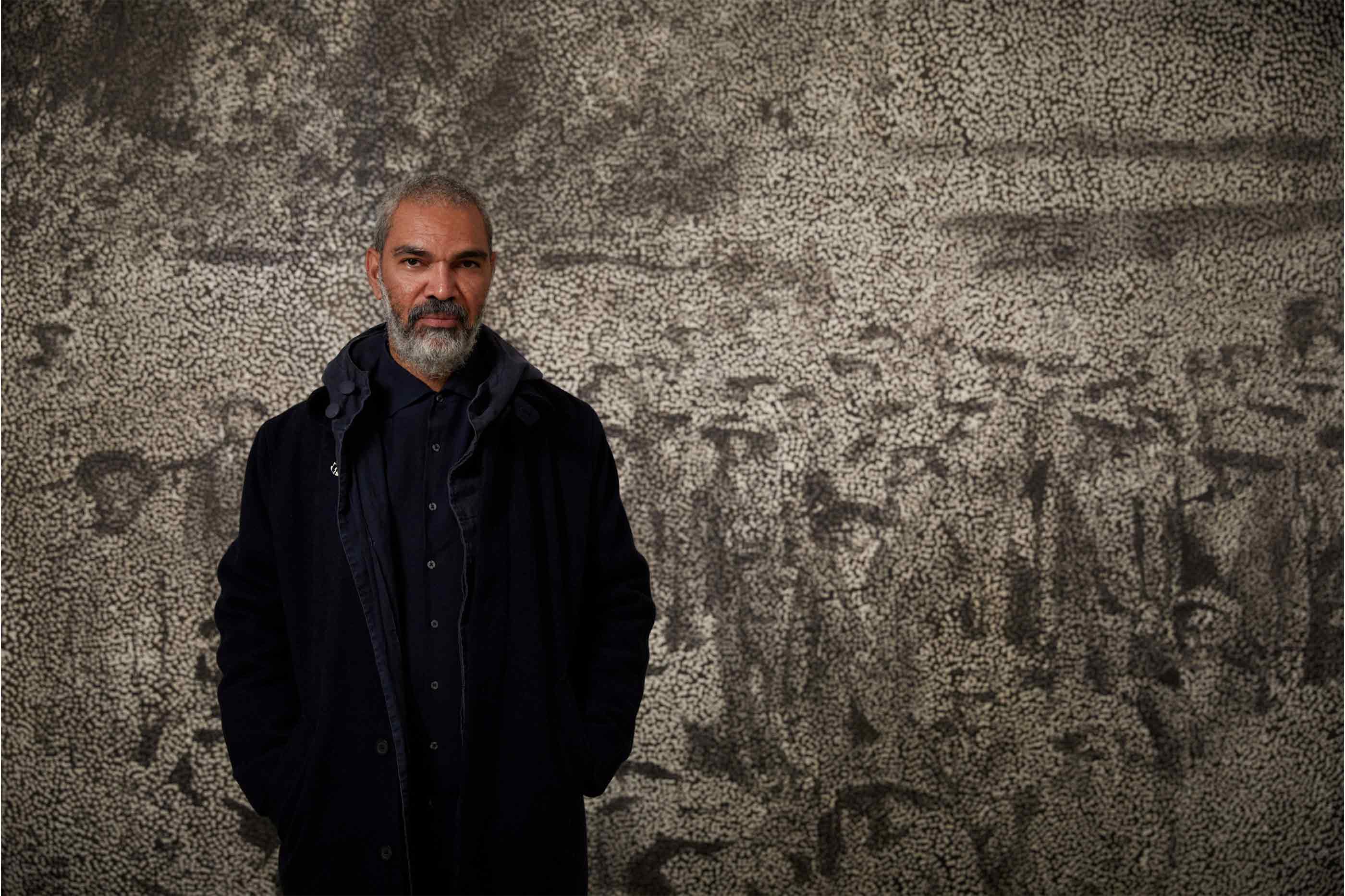

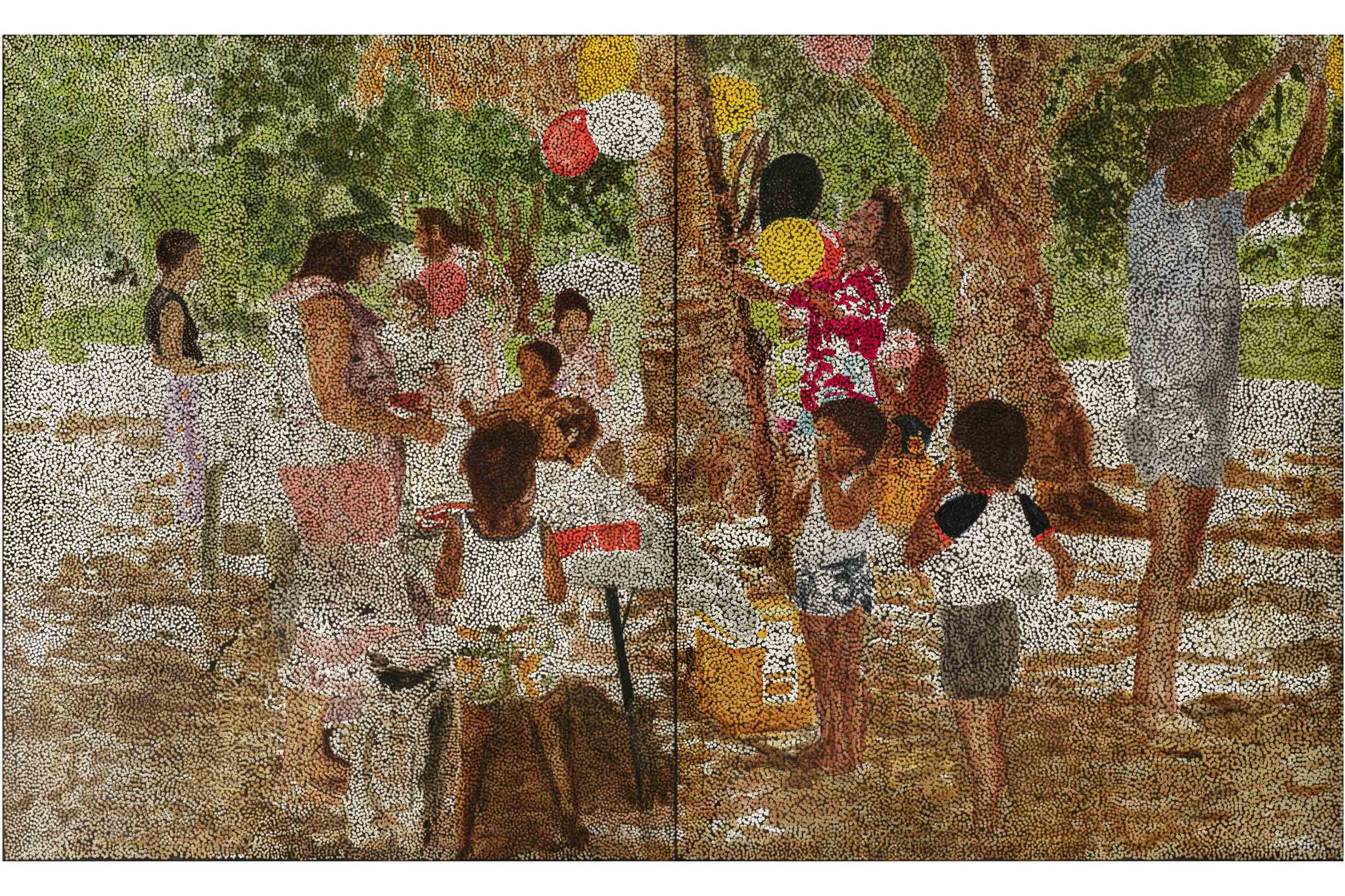

Daniel Boyd, Untitled (TBOMB), 2020

oil, synthetic polymer paint and archival glue on canvas, 245 x 396 cm; 2 panels (overall)

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, James and Diana Ramsay Fund 2020, 2020P3(a&b)

© Daniel Boyd

What strikes me is that I would consider you quite a young contemporary artist with great success, both nationally and internationally. There’s a real scope, as you’re saying, of work within the show, which covers the vastness of your kind of visual vocabulary. Would you look at this as something that is retrospective or a monograph? How do you view the show?

I kind of see it as up to this date. It is a kind of monograph because of the amount of works, but I don’t want to say retrospective, because I see it as a continuum, like, the way that the language allows itself to evolve and change with context of the works or the situation where the work’s presented. [I] just see it as a part of a whole. I don’t like the idea of putting parameters around things, or compartmentalising things – I’m more interested in the porous nature of boundaries or these parameters. So, with the work, I’m more interested in the poetic way that the work goes out into the world. Kind of like in Treasure Island, they can continue to be situated in different circumstances, have conversations with other works and be able to share that framework or that language that they create for the complexity of all these things that move out into the world.

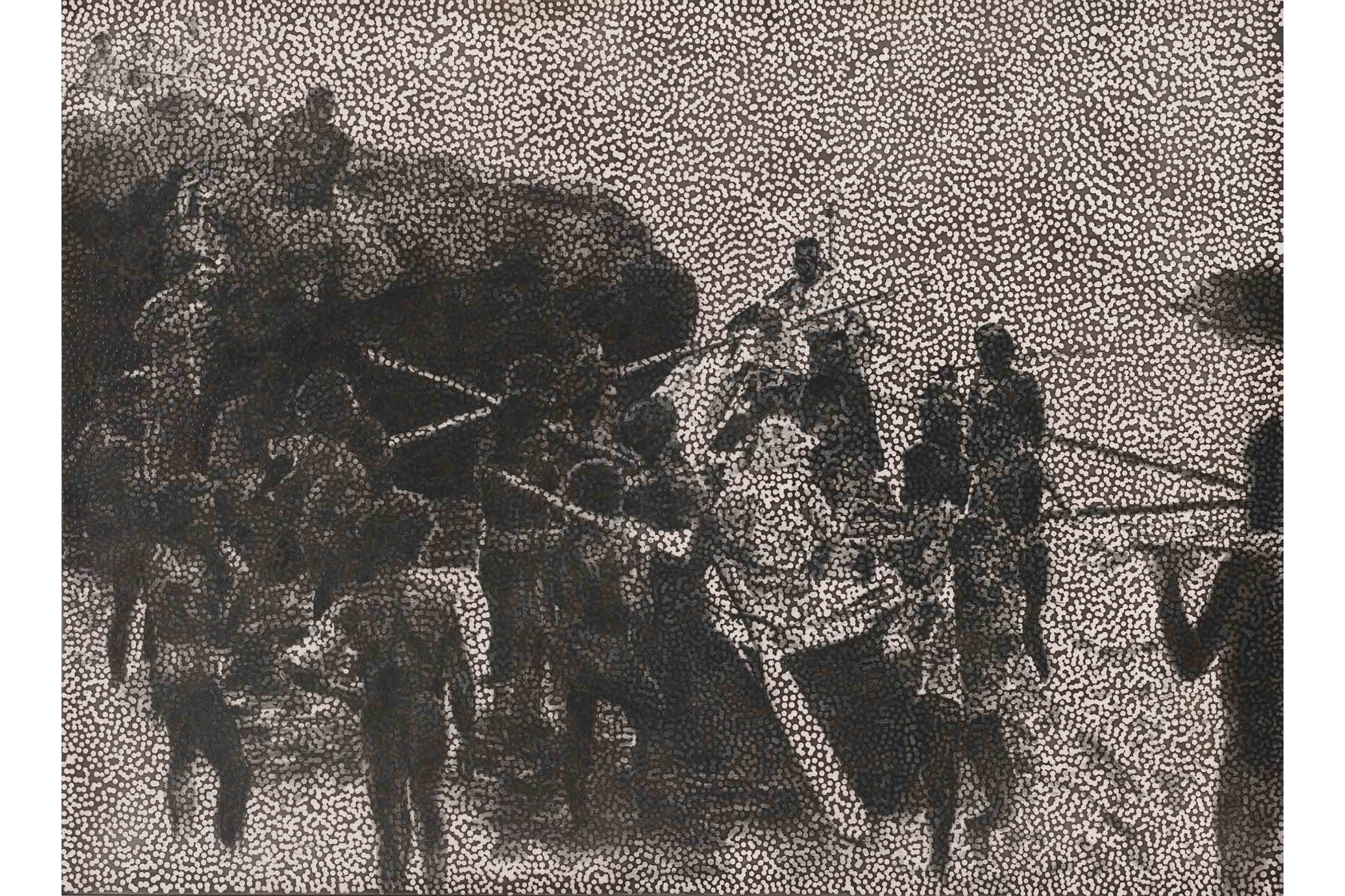

Daniel Boyd, Untitled (BNH), 2013

oil and archival glue on canvas, 122 x 168 cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, purchased 2013, NGA 2013.3985

© Daniel Boyd

The technique that you’re well known for – where the painting is partially obscured in a way it becomes about not just what is seen, but also makes reference to what is unseen – has become such a signature, I guess I could say, in your work. Tell me more about the process of that technique or why it becomes important in your works?

Initially it came from trying to understand the idea of history and representation of history – it’s kind of like a fraud thing trying to create or present something in a way that doesn’t negate other experiences. It was just about trying to create a language that made those things that weren’t present to become present in a way, acknowledging all of those things that are lost through representation [and] through a dominant lens. It was about trying to create different ways of seeing, or equitable ways of seeing. I guess, if you understand the paintings as a series of lenses, it’s like how the audience activate the work. It started with light, and the way light activated the surface of the works, but also the audience was always paramount in the way the art is situated, or activated. It’s always giving the audience a feeling of connection to another human’s experience, [and] that’s what it was about – sharing my experience, but also having the viewer or the audience activate that work.

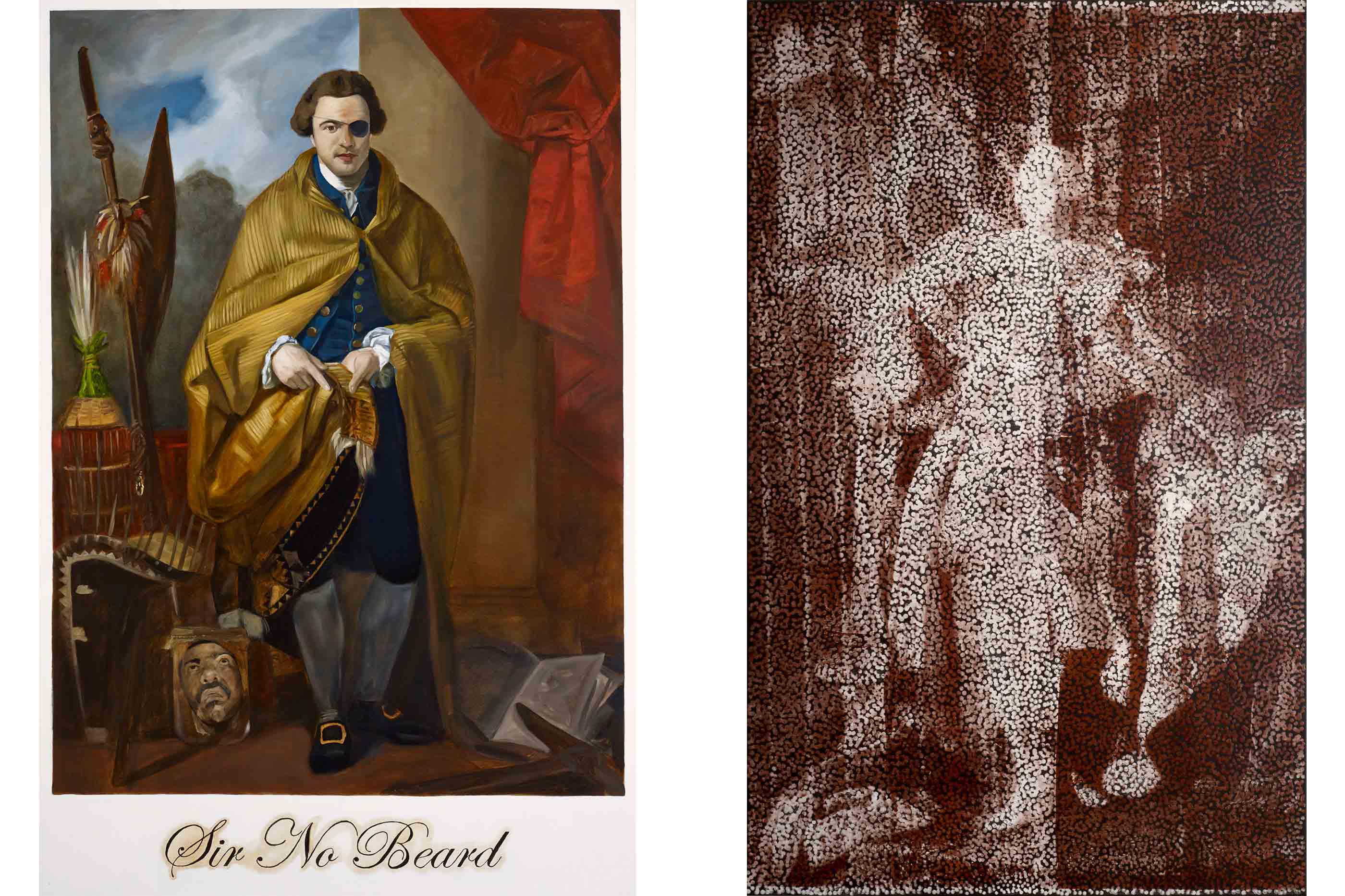

LEFT IMAGE:

Daniel Boyd, Sir No Beard, 2007

oil on canvas, 183.5 x 121.5 cm

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, gift of Clinton Ng 2012, donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program, 378.2012

Image: AGNSW, Felicity Jenkins

© Daniel Boyd

RIGHT IMAGE:

Daniel Boyd, Untitled (KGAR), 2017

oil and archival glue on linen, 244.5 x 153 cm

Collection of Brooke Horne, Sydney

Image: Jessica Maurer, courtesy the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

© Daniel Boyd

One thing that really struck me was looking at Western art theory and how so many artists over generations have been influenced by Indigenous art, and you mentioned that they are referenced but not interrogated or questioned within the idea of appropriation and that probably they should be, which is what your work does?

With modernism, it was like this singular mode. It was from a very Western vernacular [and] it was doing things without understanding the repercussions of this authorship or owning these particular ideas, or it was a subjugation of culture. I always wanted to make people aware of that appropriation of cultural material, so that they understand colonisation and imperialism through modernism. If you’re a contemporary artist, you have a connection to Western art history – there’s no way around it – and I think what is really important about art that’s being made at the moment is it’s becoming more present. So the peripheries, decentralising, these modes of thinking, it’s really important to kind of reassess those things and ask questions about how important these works were or these objects were in the way that they were subjugated to dismantle previous lineages within the Western canon. I think it’s just about acknowledging those influences and so people can understand how the cannon is being expanded.

Daniel Boyd, Untitled (BFS), 2017

oil and archival glue on polycotton, 170.5 x 216.5 cm

Artbank Collection, Melbourne, 14807

© Daniel Boyd

In keeping with those conceptual themes, another subsection, a very important one of the show is going back to much earlier in your career, the, what I call “explorer paintings,” or images of historical figures of navigation, which are very loaded in their own right, but also I feel have quite an element of humour attached to them. Would that be correct in your analysis?

Well, you know, it was always about representation, and the power of representation. When I was at art school, I began to question what these icons meant to the idea of nationhood in this country, but not only this country, but the idea of Western expansion – imperialism. Reassessing these iconographies was an important tool for me to question the imbalance in that representation. I never saw myself associated with that historical representation, or that narrative. I think if you fall into a trap, if you continue to perpetuate these imbalances that create, [then] these mythologies are created around these icons. If you disassociate them from all other human experiences that have happened on this land, then you create a situation where you start to believe the things that aren’t true, or things get skewed. And so, these paintings in the beginning were about shifting that representation so that there were more equitable ways of seeing my understanding.

Daniel Boyd, Untitled (TOTSOTO), 2021

oil, acrylic and archival glue on canvas, 143 x 215 cm

Collection of Kalli & Brian Rolfe, Melbourne

Image: Courtesy the artist and Station Gallery, Melbourne

© Daniel Boyd

When I look at the culmination of the work, there’s a room that finishes the show, which has still anthropological reference images, but then images of family and it’s interesting knowing and understanding the link between those is much closer than what people would ever think or understand, or how intrinsically placed the past is within our present as Indigenous people. I was wondering if you could talk about the relationship between those images, your family, and maybe your way of finishing the exhibition on something that I would consider deeply personal?

It also goes back to representation. If you create a false idea of representation, or if you look at it through a lens that is skewed, then the way you understand a person or its people, the people within those images, then I think that’s where things like racism propagate – they exist in this place of misunderstanding through misrepresentation. And you have the lens of science, anthropology and so a couple of the paintings in the final room are about thinking about authorship and also shifting what they mean is as images or [as a] representation of people – it’s like a photograph that relates to this lineage of misrepresentation through science. But then, it’s also me shifting that to something that’s more personal, what it means to view or understand that it’s presenting multiple entry points. It’s trying to add a softness or a beauty, like it’s sharing a lived experience, so it negates this way of looking at these humans through the lens of science, [and] it makes it more human by your ancestral links to people that are in these images. It’s my great grandmother, who was photographed by Norman Tyndale, and my great grandfather, but it’s negated by the fact that I’m a descendant of these people. I give it a different kind of authorship and a different way of seeing it – it’s more personal. It’s a way for the audience to be able to connect with it in a different way that’s not skewed by misrepresentation.

Daniel Boyd, Treasure Island, 2005

oil on canvas, 175 x 200 cm

Collection of James Makin, Melbourne

Image: courtesy James Makin Gallery

© Daniel Boyd

In a way, you give it the voice that it was denied. It’s as it was being taken.

Yeah. There’s a painting of my mother and I in the final room and it’s a way for me to kind of underline the presentation works on Treasure Island by sharing that lived experience. It’s an image of my mother and I, but it’s very complex and our relationship was deep and it speaks to all of those different things. It’s not just a photograph of a particular moment in time and space, it triggers different kinds of ideas, memories, and experiences that are about us creating artworks that continue this poetic continuum of culture. I think what I was saying before about the parameters, it’s not this empirical way of understanding things. I’m not interested in the boundaries that exist, or that are placed around things to simplify them. I’m more interested in the intuition and the culture that moves out into space in a more poetic way. We have the oldest continuous culture on earth.

LEFT IMAGE:

Daniel Boyd, Untitled (BAT), 2020

oil, acrylic, charcoal and archival glue on canvas, 213 x 198 cm

Johnson Collection, Sydney/London

Image: Courtesy the artist and Station Gallery, Melbourne

© Daniel Boyd

RIGHT IMAGE:

Daniel Boyd, Untitled (ILYM), 2021

oil, charcoal and archival glue on canvas, 183 x 132 cm

Collection of the artist

Image: AGNSW, Jenni Carter

© Daniel Boyd

To experience RUSSH Home in its entirety, issue one will be available on newsstands from October 20 and through our shop. Find a stockist near you.

COVER IMAGE:

LEFT IMAGE:

Daniel Boyd, 2022

Image: AGNSW, Jenni Carter

RIGHT IMAGE:

Daniel Boyd, Untitled (ILYM), 2021

oil, charcoal and archival glue on canvas, 183 x 132 cm

Collection of the artist

Image: AGNSW, Jenni Carter

© Daniel Boyd