If patience is a virtue, then Melbourne-based beading artist Camille Laddawan must be a saint. Where one might enlist machines to reduce the boredom of repetition, Laddawan surrenders to the intention and discipline involved in threading together tens of thousands of beads by hand. Piece by tiny piece, Laddawan sits vigil at her loom, gently thumbing beads along a thread, an artform that painstakingly offers her little emendation.

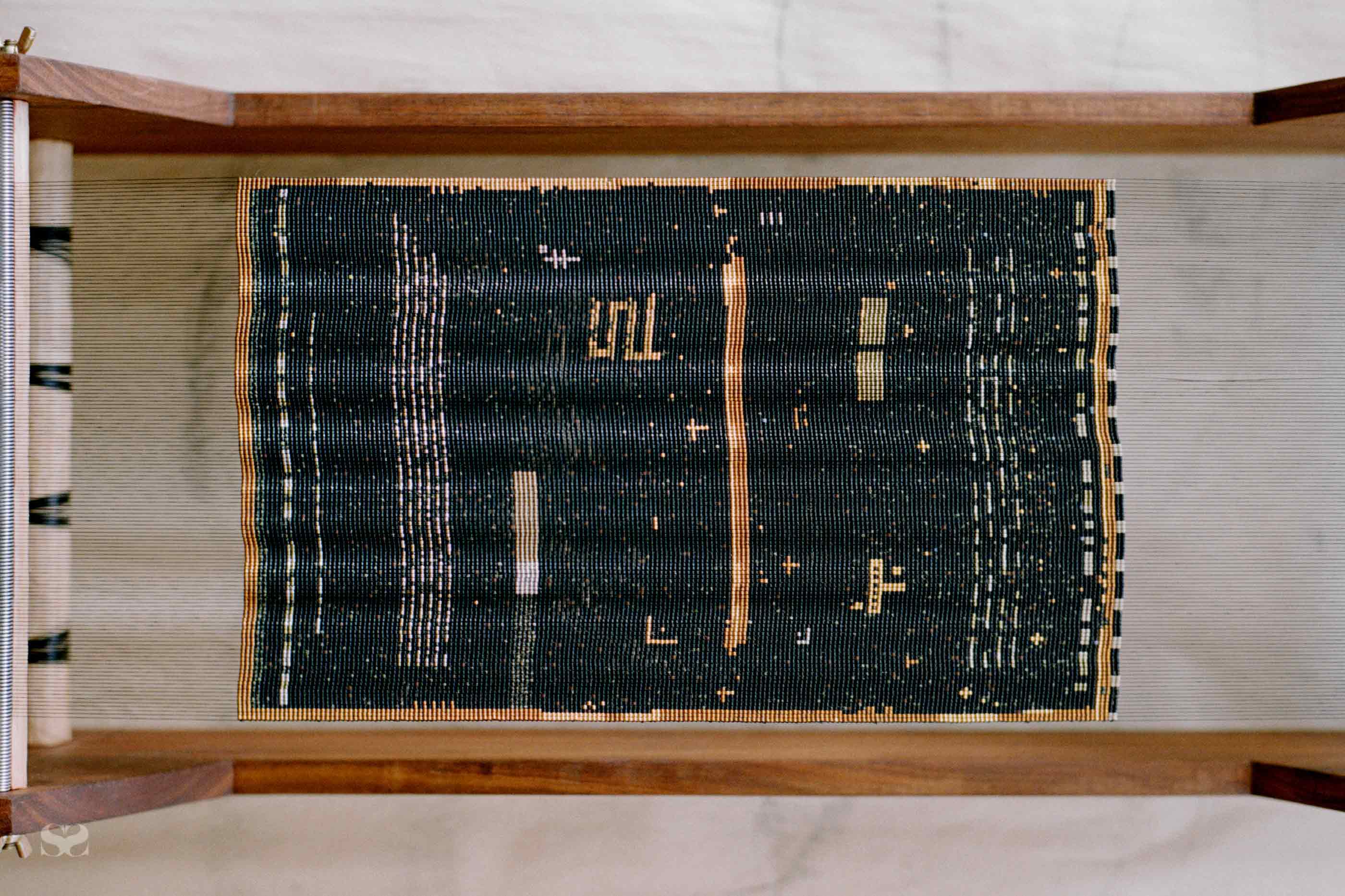

Her patterned tapestries are imbued with latent meaning, messages enshrined like sparkling glass and precious metal constellations. Familial letters, music fragments – even government emails – are whittled down into a visual score, an abstraction of time and sound diligently bound together.

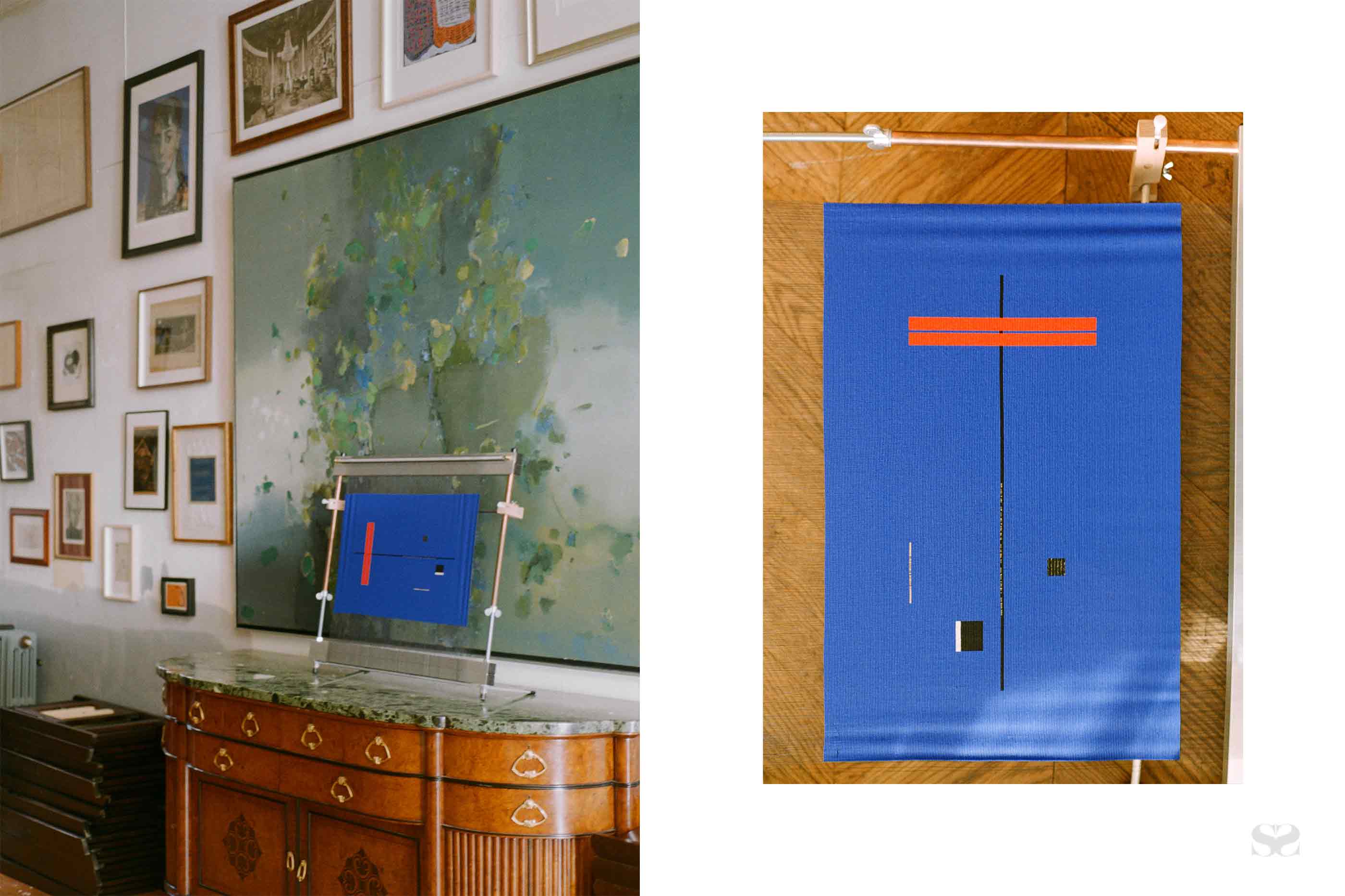

Favouring a palette of supple pinks, sea-glass greens, inky blues, and sun-baked earthy reds, she works her hands around each gridded frame for hours, every piece a vehicle for her wide-reaching ruminations – from our seemingly innocuous interactions with institutions, to our relationship with death and the body.

Here, Laddawan speaks on the evolution of her creative practice, her aesthetic and philosophical inspirations, and using her art as a conduit for unbarred communication.

I like the idea of my body going, fully and all at once, 2022, glass beads, palladium, 24k gold, thread, 330mm x 205mm.

What was your upbringing like and how did you become interested in beading as an art form?

My upbringing was a combination of dysfunctional, social and creative. I was surrounded by an eccentric and ambitiously artistic family. My mother is a scientific and natural history artist, who taught painting and drawing at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Melbourne for 20 years. Growing up, my sister was a talented violinist, and my grandmother was a photojournalist and an aid worker for children.

Beading as an art practice speaks to the inherent creativity of my upbringing, but it is also a highly organised artform that’s full of arithmetic, gridded structure and uniformity. The language embedded into my work, through code, reflects my ongoing desire to communicate, to understand the way words hold power. This combination of aesthetic and literal forms of expression allows me to explore the social and collective constructs of speaking, writing and reading.

How would you describe your approach to creating art? And has this changed over time?

Prior to finding beading, I was driven primarily by experimenting with materials and mediums. In my earlier teen years, I looked to master photorealism. In my twenties, I moved towards the other end of the spectrum, sculpting biomorphic forms in limestone and painting expressionistically with oils.

Now, in my thirties, my work is much more conceptually driven, informed by research into the ideas I am seeking to understand.

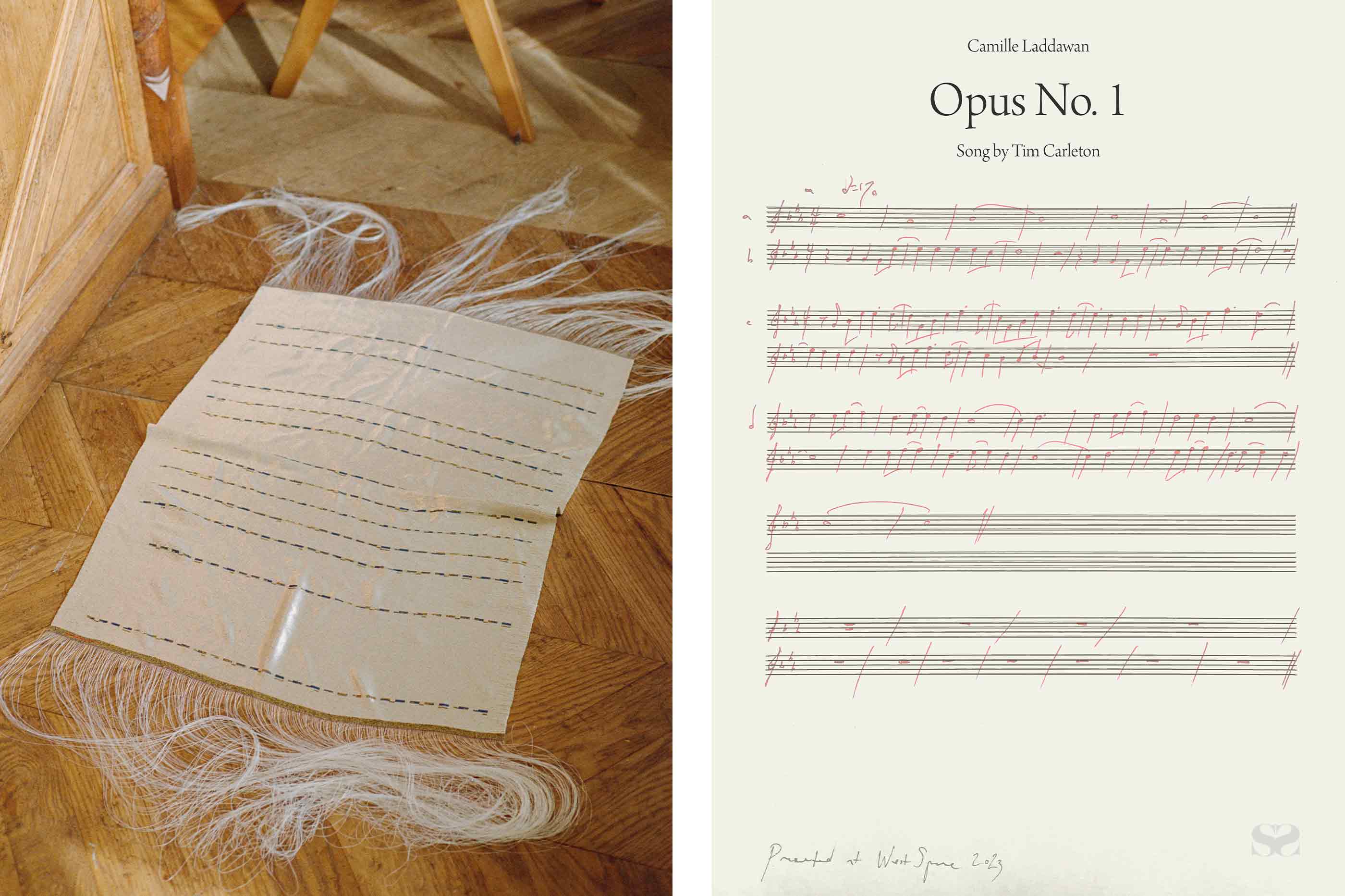

Left: Opus No. 1 (off the loom), 2023, glass beads, sterling silver, thread, 770mm x 620mm. Right: Opus No. 1 — Hand written sheet music.

You live and work in a shared creative space. Do you think your practice has been informed by your close proximity to other creatives and the space that you cultivate collectively?

I live in an old Victorian shopfront called Collingwood House, with my partner Roslyn and our dog Ru. Roslyn and I have always shared a vision of living and making art, of blurring the lines between the two. Part of this for us, is having a home that is also shared with and frequented by other artists.

We have converted two rooms in the house into artist studios, which currently occupy three poets and an artist. Roslyn and I also have studios and make our work from home. We regularly host readings, exhibitions and performances, which bring so much creative life into the space, and connect peers from different artforms together. There is always an opportunity for spontaneous conversation about materials and concepts, or just the encouragement to keep going.

Is there a period of time in history or in your life that you draw inspiration from?

Aesthetically, I am drawn to 20th Century modernists such as Agnes Martin, Anni Albers and Ruth Asawa. The clarity, simplicity and depth of each artist’s practice is a sustaining source of inspiration, both in their ability to master their craft and to push the boundaries of their materials, but also in what they were aiming to do conceptually.

Three, Two, One,2022, Glass beads, thread, 610mm x 385mm.

Art can act as a conduit for connection across cultures and generations. What has your experience been like connecting with people through your art and practice?

Much of my current work is concerned with questions of lineage, inheritance, culture and migration. My mother was born in Thailand and moved to Australia when she was seven. On one hand, we have a full family archive of photos and documents, but on the other, lots of the stories from the Thai side of my family have been lost, along with language and culture.

I am currently making a series of beaded kites with these stories and landmarks woven into them. Kite-fighting is a game my mother and uncle used to play in Thailand, and the idea of trying to fly a beaded kite weighed down with these stories, encapsulates this feeling of connecting across cultures and generations.

The importance of artmaking as a part of cultural storytelling is so important, as it has the ability to communicate beyond language and beyond words: to communicate emotionally, which is a different way of connecting with people who share similar stories, as well as people who are learning about these kinds of experiences for the first time. Art has the ability to break down the social barriers that are inherent in language, and this is what I seek to do in my work.

Opus No. 1 (off the loom), 2023, glass beads, sterling silver, thread, 770mm x 620mm.

You’ve devised what you call a ‘Tone Code’ to inscribe messages and even fragments of music into your artwork. How did this come to be, and what sparked your interest in non-verbal styles of communication?

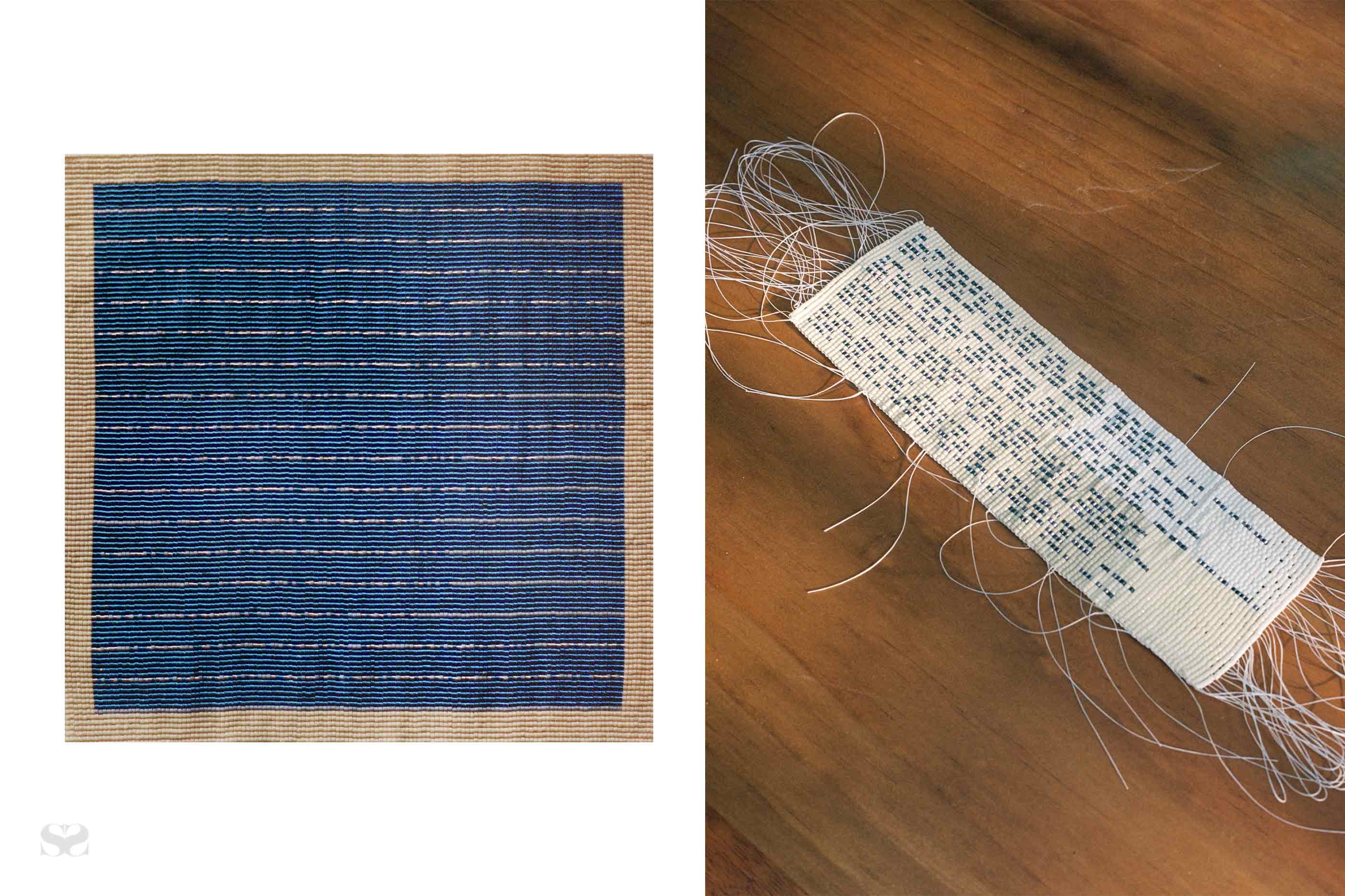

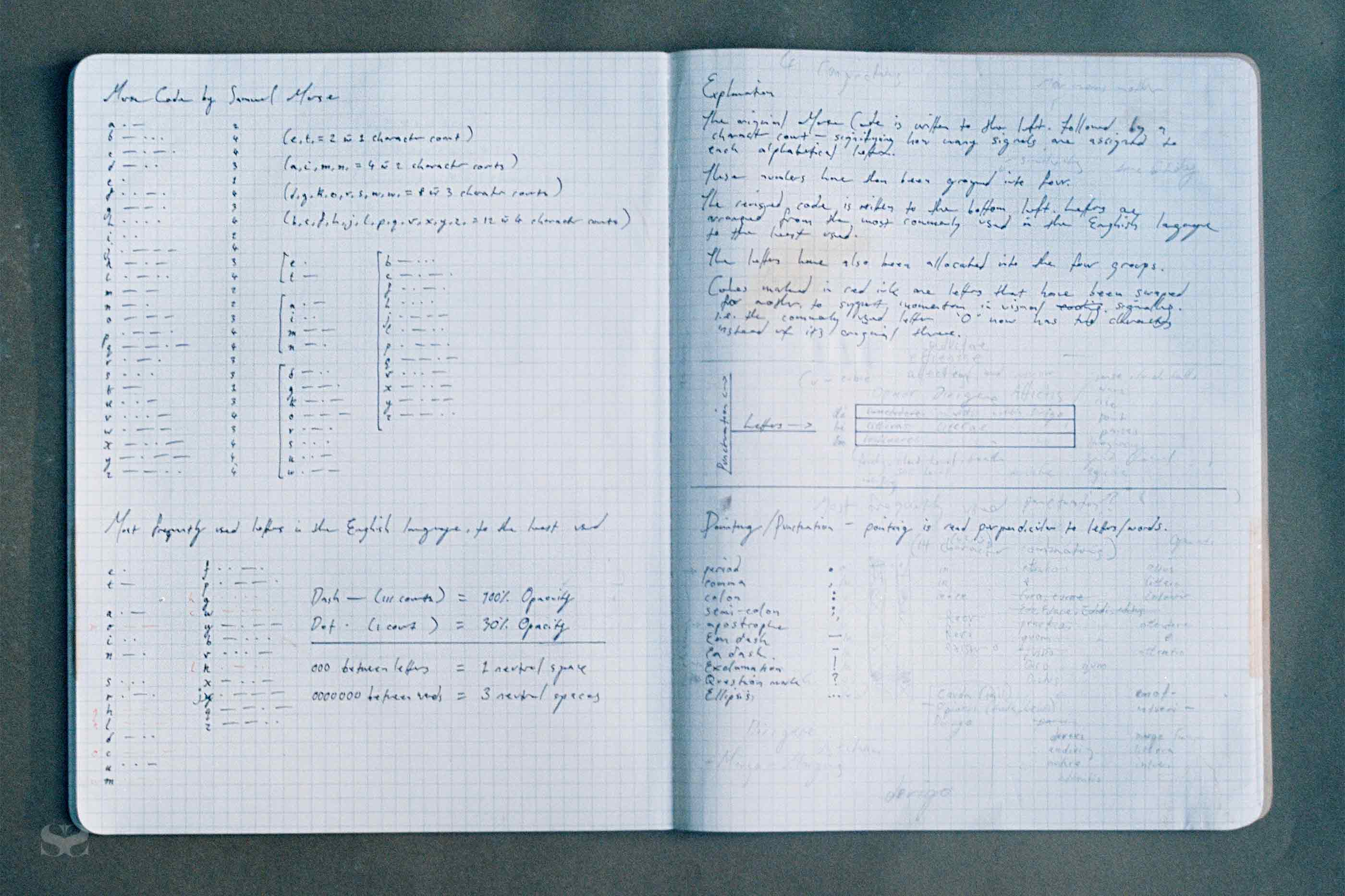

Tone Code is a visual alphabet that I have developed as a way to combine aesthetics and language into a cohesive system. Tone Code is similar to Morse Code, however, instead of using combinations of dots and dashes to make letters, Tone Code uses combinations of light and dark beads.

I have also created code for punctuation, again assigning unique combinations of light and dark tones to each punctuation mark. More recently, I have developed a Music Code as well, which uses a similar methodology, translating notes and rhythms into combinations of light and dark beads.

In my adult life, I have come to learn more and more that language and words hold power, and that this is the primary way we communicate and make meaning. The implication is that people who don’t have words, whether that be from experiencing trauma, cultural displacement or when trying to speak out about an issue in a context where there are no ready channels to be heard, these are all instances where language as a system fails. Creating the code was a way to convey this experience visually. I wanted to be able to embed literal meaning into my works, but for those meanings to remain obscured, to relay the experience of this power dynamic.

You studied art therapy at university, how does this inform your practice?

My final thesis for my art therapy Masters was concerned with the neurological responses that individual children experience when using various art materials, and how art materials affect different children in different ways.

This study also helped me to understand why I have been drawn to beading. Beading is a committed process that requires full attention, patience and stamina. There is a mathematical element, requiring me to measure and count each bead and row. I find beading calming, with its various sequences of repetitions and patterns. I think this strange desire to devote so much time organising tens of thousands of minuscule beads and threads into rows provides an anchor to my mind, which can otherwise tend to wander.

Left: Steven, 2022. Glass beads, thread, 198mm x 198mm, Right: Parallax by Don Paterson, 2021, glass beads, thread, 60mm x 190mm.

Can you tell me about your most recent work ‘Opus No. 1’?

Opus No. 1 is a large beading made of sterling silver plated glass seed beads, embedded with rows of music code woven in blue and brown beads.

Opus No. 1 refers to a piece of music written by Tim Carleton in 1989. He composed it as a teenager in his garage, on a 4-track tape recorder. This piece is now the world’s most popular hold music, used by many institutions, including the Australian Government’s social services program, Centrelink. I have transcribed this piece of music into a visual code and woven it into the grid of the beading.

I chose this song to think about the function of hold music as an institutional tool that holds a person in time, whilst waiting for a specific outcome. There is a philosopher from the late 1800s called Henri Bergson, who distinguished between ‘clock time’, which is the kind of standardised time we share in order to function socially, and ‘lived time’, which is the personal or inner experience of time we feel individually. ‘Lived time’ can sometimes feel fast or slow, depending on what you’re doing, how you’re feeling, or what’s going on around you.

Music, it seems to me, is a medium that operates as a bridge between these two kinds of time. Music scores mark time through space (clock time) whereas listening to music is aligned with lived time (inner experience). The Music Code embedded within the lines of the beading represents this sense of mechanical time: a timeline constantly moving forward. However, when you look at the work as a whole, and realise how every single bead has been individually threaded over the course of 200 hours to make a dense fabric, your sense of time is expanded. My aim with this work was to render the timeline of the music visible, to create this sense of being ‘held’ in time.

Initial Workings, 2021.

Where can we expect your work to go in 2023?

Over the past year, I have spent time expanding the techniques of my practice – making larger, more ambitiously scaled works, as well as moving away from two-dimensional forms to experiment with more sculptural beaded forms.

I’m excited to be sharing some of this work at the Australian Design Centre in Sydney towards the end of the year, following a residency at Bundanon. For a solo exhibition in Melbourne next year, I’m developing a body of work based around a collection of plant seeds held at the Kew Botanic Gardens that were collected by English/Irish botanists in Thailand in the early 20th Century. I will be making a series of giant beads that reflect the migration patterns of these seeds, linking them back with stories of migration on my matrilineal side.