In partnership with Penguin

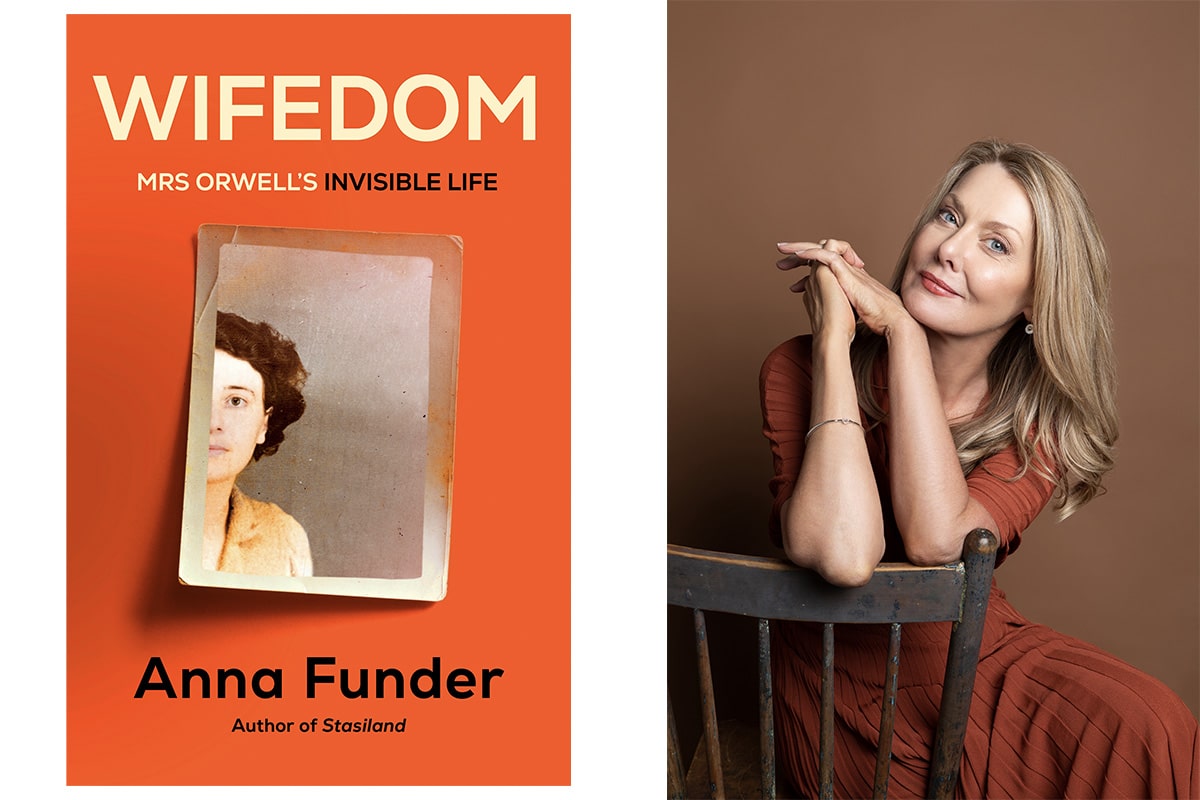

Think you know George Orwell? How about his first wife, Eileen O'Shaughnessy, ever heard of her? From Tolstoy to Fitzgerald, the wives of male authors have famously gone uncredited and their efforts egregiously downplayed. In her latest book, Wifedom, Anna Funder rescues the woman responsible for Animal Farm from history's dustbin.

The author of All That I Am and Stasiland has moved on from tales of Nazi Germany and stories from behind the Berlin Wall, instead turning her pen on one of the harshest critics of both regimes. Written over six years, the idea for Wifedom came after Funder discovered six letters from O'Shaughnessy to a friend, their contents painting a portrait of marriage, domesticity, and writing contrary to all of the biographies written on George Orwell deigning to mention his first wife. In Funder's eyes, the omission was symptomatic of a greater problem: the way patriarchy erases the contributions of women. More importantly, she had a feeling the same mechanism at play then, had survived into our current day.

On the eve of Wifedom's publication, RUSSH spoke to the Miles Franklin Award winner. Find our conversation, below.

Unfortunately it's not an uncommon story that wives of famous male authors are written out of the picture. Why did you decide to explore the marriage between Eileen O’Shaughnessy and George Orwell in particular?

I have always loved Orwell. He is really very funny and good at writing about power and tyranny from the point of view of an underdog. And all of his biographers are men and write about Orwell as this self-made genius who did everything alone. But in 2005, six letters from his first wife, Eileen, to her best friend were discovered that no one had known about before. All of a sudden, you can see that he had this incredibly clever, funny wife and the story of their marriage, from her point of view, is completely different from how we've read about it in history. And so it struck me that there was an underdog in his own life, one that had been erased in the story of his career and success.

Eileen writes one of the letters six months after her wedding to Orwell, and she tells her friend that they had argued so bitterly since that she'd thought to just write one letter to everyone "once the murder or separation was accomplished". However, in the biographies all of the authors write that during those months after the wedding "conditions were perfect for him"; he was enjoying Eileen's company and he'd never written more or better. So my book endeavours to bring her back to life through these letters and understand how Orwell and these biographers left her out of the picture.

Was it a lack of information, laziness, deliberate omission or just negligence?

I think it's much more systematic than that. Part of the way in which men are made into the main characters of the world, so to speak, is to leave out the women who helped them, mentored them, sponsored them, edited them, funded them; the mothers and aunts and wives and so on.

My book is an attempt to say, "hang on a second, if we look at this relationship of 80 years ago, which is kind of extreme and interesting and amazing, why does that mean something to me, a privileged white woman in a wealthy country like Australia?" Let's have a look at the mechanisms. How did that actually happen? And are those mechanisms still in play today? And I think some of them are. So that's what I'm really interested in.

Rereading Orwell with all you know now about their relationship and Eileen's involvement in his work, could you recognise her voice in the writing?

So his most famous book, Animal Farm, was written by Eileen and Orwell together. They wrote it during The Blitz, and Orwell had wanted to write an essay that was critical of Stalin, especially in the wake of their experience during the Spanish Civil War where Eileen saved them both. But at that point Russia was helping the Allies, so no one would've wanted to publish the article. So Eileen, who had more political sense than Orwell, said "an essay is not a good idea, let's do it as a fable". She'd studied fables under Tolkien at Oxford and so they wrote the book over three months in the winter of 1943-44. She went off to work at the Ministry of Censorship every day to support them financially, then would come home and comb over what he'd done.

Animal Farm is an outlier in his works; when it was published his best friend and publisher said "they had no idea he was capable of this". Even though they all knew Eileen, they could not attribute it to her, as if it would take away something from him.

They'd rather it be a miracle than a woman. Tell me about their marriage. Was it all horrible, all the time?

They were married for nine years and I think they had a lot of good times. They had dinner parties, they had a lot of friends, they had adventures – but he was unbelievably unfaithful. He would proposition women left, right and centre and rub her face in it. He tried to sleep with one of her close friends, Lydia, for instance. He also had tuberculosis so he was really sick a lot of the time, which is the other thing. So she was looking after him, keeping him alive and presumably not wanting to leave him in case he didn't have long to go.

She wrote a poem called 1984 before they ever met and it was about projecting a future of dystopia and mind control. Then after the relationship is over, he calls his last novel 1984.

The term 'wifedom' is really interesting to me. How did you land on this as the title for the book?

It took me six and a half years to write this book. At some point I had to ask myself, "what am I writing about?" Because I'm trying to bring a woman back to life and I'm trying to show how it was that her husband, his biographers, and history have buried her. I'm also writing about a condition or a construct. To be a wife is traditionally to work in the service of your husband; the labour they take on is viewed as part of their good nature, it has no monetary value and it's invisible. That struck me as a little bit like serfdom.

What was the research process like?

Orwell's second wife, Sonia Orwell, and a man called Ian Angus collected his journalism and essays and put it out in four volumes after he died. I read my way through that, which was fantastic. Then I read those six biographies, which is when I found the letters, which led me to read a large portion of the sources those biographers cited, which showed me exactly what they'd left out. I even read the interview notes of one of the biographers, Sir Bernard Crick, who recorded in an interview with a woman Orwell wanted to sleep with, Brenda Salkeld, that she had commented on how Orwell "didn't like women very much, I suppose that was partly because he was a sadist". And Crick just leaves that out, but Orwell writes about sadism so it's a completely relevant fact but because it's so hard to fit with the image that the biographer wants to make of this decent genius, it's just left in the archive.

Why do you think we're revisiting these kind of narratives about forgotten females in pop culture now?

I think it's high time. I think there can't be too much of it. If looked at another way, we've had a lot of male-centred narratives for, I'm going to say, 10,000 years? So these stories are new and fresh. Also, if you're telling the story of somebody's wife, and the man is interesting, then you're telling the story from the closest, most intimate, and probably most knowledgeable point of view that there is.

What is your role as an author in a story like this?

This book is not easily placed in genre. I could have written a novel about Eileen, it would have been a lot easier. But I wanted to show the sly ways that she's been hidden, because I think they may still be in operation today. Whether that's the use of passive voice, or the minimisation of the work of life and love, which is so often referred to as domestic, yet it keeps everyone going.

Do you think of Wifedom as a departure from your previous works like Stasiland and All That I Am?

What all these books have in common is that they're innovative in form, but I don't set out to write something that is innovative in form, I set out to write books that are a contribution to or an intervention into stories that were not or are not being told.

But my husband said to me recently, "first you take on the Stasi, then you took on the Nazis, now you take on patriarchy. Are you done?" (laughs)

Wifedom by Anna Funder was published on July 4. Secure a copy through Penguin or at your local bookseller.