"The amount of experience that we go through, in doing what we do, is many lifetimes. The problem is holding on to a fixed point for long enough to understand it,” says Michael Hutchence in the opening sequence of director Richard Lowenstein’s new documentary, Mystify – a glimpse into the troubled heart and soul of the lead singer of INXS, woven together from an archive of rich imagery, Michael’s private home movies and those of his lovers, friends, and family.

I look back at Lowenstein’s work – be it Dogs in Space, the many incredible INXS videos, Autoluminescent, He Died with a Felafel in His Hand – and feel that the quote rings so true for Michael, for INXS, but also for so many of the musicians that came out of that era in Australia and New Zealand in the 1980s and 90s. My Dad [Mark Callaghan of GANGgajang] being one of them. I feel a strong connection with so much of that music – I often get emotional listening to it, and it’s hard to explain or articulate why.

I will never forget the time I went to see Australian Made, a concert film by Lowenstein chronicling the music festival of the same name that toured Australia in 1986 and 87, featuring the likes of the Divinyls, Mental as Anything, The Saints and INXS, amongst others. I remember finding myself in tears watching the Triffids perform Wide Open Road – and looking across to see my older brother was in the exact same place, overcome with emotion.

Returning to Michael’s quote, I think that time for music here in Australia and New Zealand was magical, and feel that my parents and their peers, as they have grown older, have come to realise just how special it was too. Maybe it’s taken some time to really see it clearly – so timeless, effortless and remarkable in my eyes. Or maybe that’s what happens to any human as they grow older – we see things in a different light with the gift of hindsight. In the tragedy that was losing Michael Hutchence, he wasn’t given the gift of holding onto that time to fully understand it. He was taken too soon. Having recently lost someone close to me to suicide, seeing this film only highlighted the feelings I have also felt – that there is no sense. But there is legacy. And through the gift of Richard’s work, we are very lucky that this moment in time was carefully and beautifully documented. On another note, I am very excited to one day see some footage that Michael filmed during my parents’ wedding that is in Richard’s archives. It’s all a reminder to document life in whatever way you can – it is far too precious not to.

Hi Richard, how are you?

Hi Kitty, I’m good.

That’s good. Are you in Perth?

No, I’m in Melbourne.

OK, I thought I saw something online about the film being premiered in Perth yesterday.

Yeah – they had a screening in Perth, but they wouldn’t fly me over ... Thanks for coming to the screening in Sydney.

I was thrilled to be there. It was so good.

It was good to meet you, and understand the connection and everything. I am still going to get the tapes from your Mum and Dad’s wedding to them.

Oh, I imagine there is a lot going on for you right now. There is no rush with that.

Yeah, we can do it. We have someone here who can pull it out and make a copy.

Wow, I have never seen it, so that’s exciting. So, I guess we will get started. I don’t often do this [interview people], however, this is probably one of the most exciting things to talk about for me. I love INXS, and I love everything that you have ever done too. Did you feel any fear or pressure in piecing together this story, or did this come naturally to you, given that you spent so much time together over the years both professionally and as friends?

I don’t think I felt any fear, because I am not sort of built that way, I just sort of keep going forward, and I am really stubborn – I sort of just keep pushing. When the initial idea, or the decision to do something clicks into me, I just sort of keep pushing forward against all of the obstacles. It was certainly a hell of a lot of stress, all of the practicalities. I knew that we had – not just me, but within the entire company with Lynne-Marie Milbourne, Andrew de Groove, people that worked with us over the years on videos and everything – I knew that between us we had the ability to pull something out of what we had, or what we could get. But the most sort of psychologically stressful things were all of the obstacles we had to overcome, all the different commissions and the keeping family members on board and keeping the band on board, which proved very difficult. And then also stopping people from, you know, using it as a way of exploiting the situation and turning it into an excuse to sell back catalogue. It’s very difficult to keep that independence and keep that integrity, and sometimes the big companies or the management will waggle huge amounts of money. And you think – with all that money – I could make an even better film, but then you realise what you may lose. Your independence is not worth the money.

It sounds like a very delicate responsibility, and passion, I guess.

And I knew that was Michael’s sensibility, you know. He hated being a sell-out. I mean, he flipped out once when one of his songs was sold to a Sea World commercial so I knew I didn’t want it to be, in metaphorical terms, a Sea World commercial.

“As soon as he stood up at that Queensland motel and came towards me and reached down to my hand, that thing I remember was, there was no bullshit here.”

Do you think you were instantly drawn to the creative collaboration with Michael, or did it take years to shape ... Did you feel an instant trust both on your end and his in that regard, or did it take time over the years?

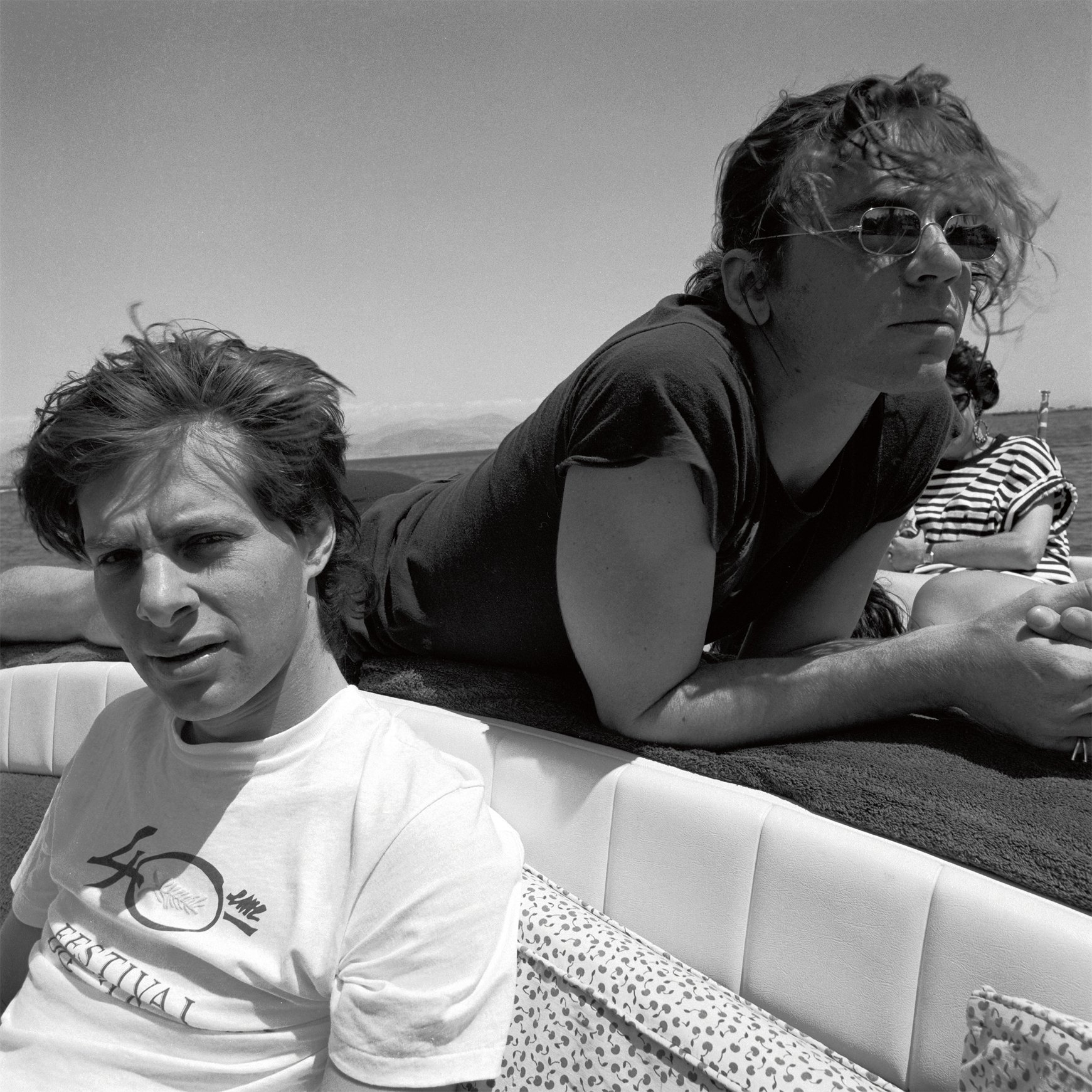

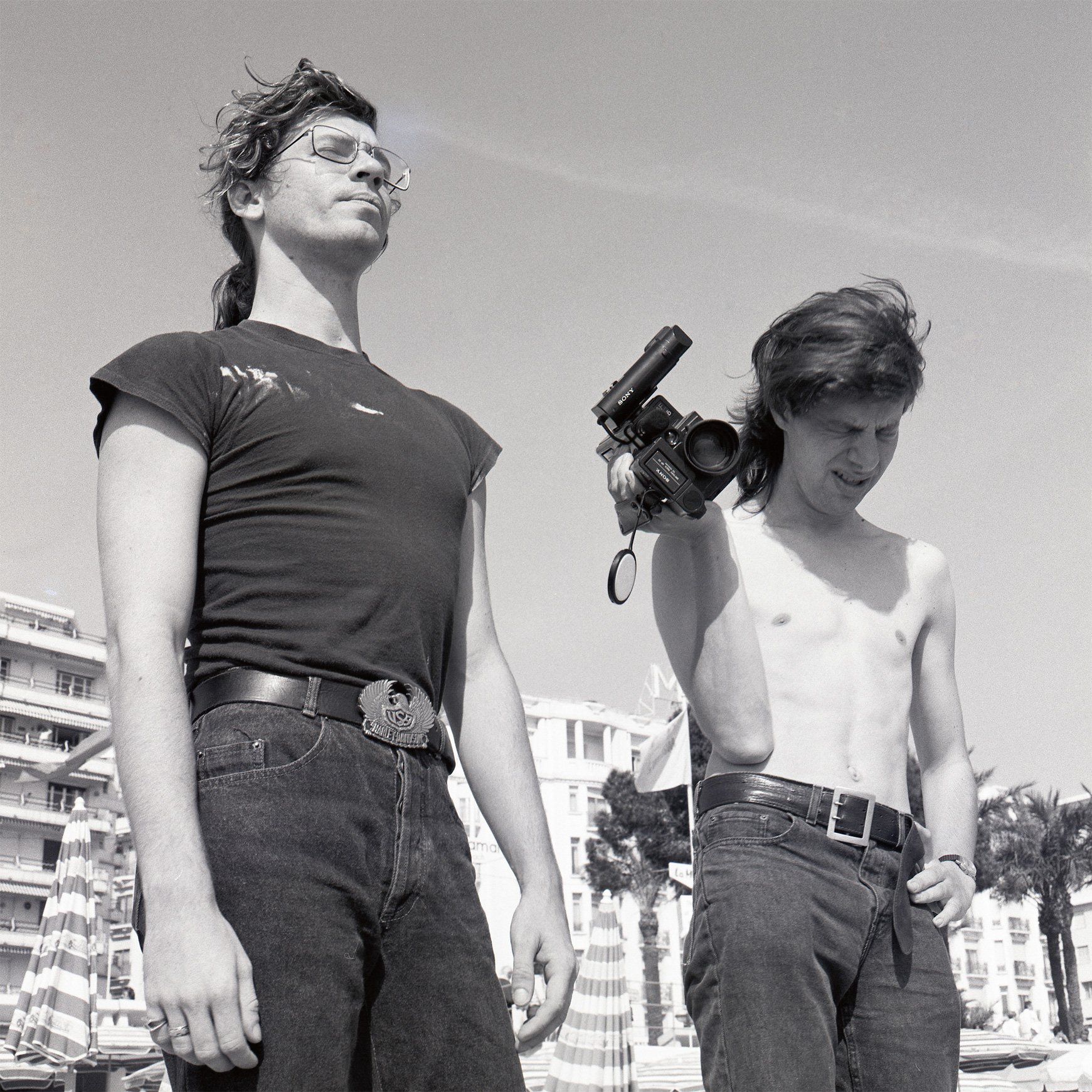

It certainly wasn’t in my mind when they first called me up in 1984, because I was a pretentious sort of Melbourne post-punk, who would only go to see non-commercial experimental music and not mainstream music, so I never really thought, ‘These are interesting people and I’m going to collaborate with them,’ but, you know as soon as he stood up at that Queensland motel and came towards me and reached down to my hand, that thing I remember was, there was no bullshit here. He’s just a genial guy with real humility, who’s not posing or not doing anything of the stereotype cliché, and he certainly wasn’t a big rock star then ... I had worked with bands before and it was not what I would usually expect. Lead singers of Australian bands are, by and large, sort of internal and troubled, and he wasn’t. I had had experience working with Hunters & Collectors and other people and a lot of band members and singers have big egos, and have sort of got masks. And I know that they’ve sort of got to create an image so you can’t get beneath the mask, where Michael was just like ... there he is: “I’m just me”. And, as I’ve said in the past, within 24 hours we were all snorkeling off the Barrier Reef and doing very un-Melbourne-like things, and then just hanging out. I think we met up in Cannes a few days later, as my first film was showing ... And then going to London – he was living in London, and so was I at one stage, and we were just hanging out, and I got to know his partner Michele Bennett very well, and it just went on from there. And then the collaboration outside of the music videos just kind of happened by happenstance. It wasn’t even me thinking, ‘This is a good idea’. I was just shooting the shit with him at a meeting in Cannes, and we just made up the story of Dogs in Space on the spot.

Where do you think, in his life, he was most settled? Where do you think he was at home?

He was definitely happiest in Sydney. But at the same time, he was a nomad. Martha Troupe, who arguably was the person who knew him the best – she was close to him like a mother, over at least a decade – she calls him her nomad. He was definitely the most relaxed in Sydney, with his Sydney friends who he knew from the old days, before the bullshit set in. They kept him a bit down to earth ... He could walk down the street, he could be real, and taxi drivers might say hello and the occasional person, but there is no bullshit in Australia. New York he was really comfortable as well, you know, it was never at a stage that, in either of those cities, he would walk out of the hotel and get mobbed. Even in the height of the craziness ... in both Sydney and New York – and Melbourne – he was able to just relax and be himself, whilst enjoying the glittering prizes of fame, in the local bar or whatever. But he certainly hated London. He ended up there for personal reasons but absolutely hated it. That sort of aspect of it that you see in the film where he walks out the door and you see paparazzi following him everywhere.

It seems like his character and personality were perceived really differently across the world and through different chapters in his life, and I wanted to ask if you have felt a different response in the viewers and the press here in Australia maybe to how it was received in the US – and if you think it will be perceived differently again in the UK?

Yeah, I think the same old prejudices are there – I mean, we had a great UK producer John Batsik, but the different psychologies are still there I feel, even in the reaction to the film that America has. You know it’s been a long time since INXS and Michael have been in the zeitgeist in America, so over there there is like this curiosity of digging up something from the past, it’s almost like going to see a story about an unknown rock star, and then they hear the music and they go, ‘Oh I remember these songs’. So many people at the Tribeca Film Festival came up and said, ‘I remember those songs but I didn’t know anything about this story, I didn’t even know the Paula Yates section’ ... that whole craziness in the press that was happening here in Australia and in the UK just wasn’t going on in America ... Here in Australia, he and the band are national heroes and much in the zeitgeist, so it’s a much more sort of intense reaction. And we haven’t screened anywhere in England, but even in the making of the film, there was a little bit of that old NME sort of old grudginess, like, ‘Yeah, great story, used to go out with Kylie, used to go out with Paula, but, you know, really the music isn’t up to U2 is it – it isn’t on a level of The Clash’ ... There’s still a bit of a colonial convict mentality looking at our music. Unless you’re Nick Cave of course, they idolise Nick ... You know I think that was part of Michael’s dilemma – and I think he was caught somewhere in-between being the stereotype of being someone in a pretty boy band and a serious rock band musician that was sort of left in limbo at the end of the 80’s.

“You watch Michael and you just wanna jump him ... And it’s not just the body language, it’s the face, and the sensibility, and the genial smile, and you feel safe.”

You’ve mentioned across a few interviews that I have read that Michael had a female sensibility. I just wanted to know if this was something that you consistently observed throughout your friendship with him, or do you think it’s something that you have further come to realise in your discussions and interviews with Michele (Bennett), Kylie, Leanne, Martha, Helena, and everyone?

No, it was pretty obvious from the start. I am a bit of an analyser of things and it was always obvious to me, and even what appeals in cinema, that full macho male iconography of the masculine man with the rippling biceps or whatever, is not actually all that appealing to women. And Michael, obviously an object of desire ... was very, very female, but, it’s an important distinction that he wasn’t effeminate, and it was female in a very heterosexual way. It’s kind of interesting that the feminine traits appeal to everyone – they appeal to men, they appeal to women – so especially as a man his own age, I looked at him and sort of said, ‘How the hell does he do it?’ ... You watch Michael and you just wanna jump him, in a way, across all genders. And it’s not just the body language, it’s the face, and the sensibility, and the genial smile, and you feel safe. I mean so many people had one night stands or casual flings with Michael, but they knew what they were getting into, like a sailor passing through town – you know. I’m not going to get hurt by this, because I know what it is, it’s just this little window, this moment with this lovely man.

“It was an incredibly vibrant time, but there is a danger of nostalgia, saying, ‘Oh it’ll never be like that again’ ... I think it can be like that again.”

I love all of the videos you’ve done for Australian and international bands. Being around so much of it as a kid growing up, I just feel like INXS are part of that troupe of Australian bands that are intrinsically iconic to our musical history, and I feel like it can never be replaced or recreated. I really envy those that were there for it, and I wanted to ask you if you were immediately struck by INXS’s talent – and everyone else – Jenny Morris, Crowded House, Cold Chisel, Nick Cave, all of that, did you realise at the time that something very special was happening? Or do you think that in retrospect maybe it was a sort of pre-internet thing perhaps, or just sheer luck?

It’s not sheer luck. That’s one of the major reasons I wrote, directed and made Dogs in Space. Because the 80s were renaissance, much like the 70s were, much like the beat area was. A renaissance of art, music and culture, across all art forms. Rather than just focus on the INXS thing, there was this huge vibrancy in popular culture, and this comes from economic wellbeing usually. You can go back to Shakespearian England and see why Shakespeare flourished. It was because there was a shit load of money out there. So the ground is very fertile for creativity. And it’s only when a society is doing well that this tends to happen, that there’s money for the arts. And there were a few things going on: it was incredibly easy to be on unemployment benefits, and what they would call the student art grants, so you could graduate from an art college or something, or leave high school, and you could easily go on unemployment benefits and sit there and start a band. And that’s how INXS started, that’s how Dogs in Space, and possibly how your Dad’s band, started too. And it was also incredibly vibrant in the arts community with all the neo-expressionism and new primitivism coming out in the 80s. And this was reflected all over the world, because the economy was booming and so there was money there – there was philanthropic money, there was government funded money, the film industry boomed. And as you say, pre-internet, so people were going to the cinemas, they were leaving their houses and going to venues to see bands in the pubs, and the pubs would hold 1000-plus people, it would be insane. Now, you just stream it all on the internet. But it’s not just the internet – it’s that money’s tight. There’s been a couple of recessions, the first being in ’89, then the GFC. Basically, recession and fiscal tightness does not create creativity. So I do think these times will come again, next time there is a boom in the economy. But it was very obvious that to sit there at 20 and think that you can have a viable career as a pop musician, you have to be in a comfortable, secure economic place in a society – and currently we’re not. I think creativity and popular culture always reflects the state of the world economy ... It was an incredibly vibrant time, but there is a danger of nostalgia, saying, ‘Oh it’ll never be like that again’, because of certain situations. But I think it can be like that again, when the right circumstances hit.