“Art is like a lover whom you run away from but who comes back and picks you up.” – Tracey Emin

Is it ever possible to separate art from maker?

It’s an often-debated notion. But in the case of Tracey Emin, there’s no question. For the artist who began her career with a series of letters to investors in her ‘creative potential’, followed by the Major Retrospective displaying intimate mementos of her life ’til then, there has never been a line to draw. And to take an educated guess, there’s no one else who has lived a life quite like Emin’s.

It was a tent appliquéd with the names of everyone Emin had ever slept with (in the literal sense) that brought the British artist into the public consciousness in 1995.

And it was her 1998 work My Bed – a forensic study of post-breakup desolation comprising a ‘box frame, mattress, linens, pillows and various objects’ (used condoms, vodka bottles, bloodstained underwear et al.) – that solidified her place there. Emin has made no secret of the aesthetic considerations that drive her multidisciplinary practice, influencing the shape and form of its autobiographical elements. But while it may not be ‘true’, it is certainly honest.

"I am not talking to people who lack empathy. If I worried about all the doors that have closed on me, I wouldn’t have achieved anything. I make the art for myself first, it goes out to the world later."

Raw monoprints that say “somethings wrong” and handwritten neons professing “Oh Christ I just wanted you to fuck me and then I became greedy, I wanted you to love me” bleed into frank interviews and longer-form extractions, like her early handwritten work, Exploration of the Soul or her 2005 memoir Strangeland, detailing her childhood of affluence, then poverty, in the seaside town of Margate, her early loves and losses, the story of her rape at age 13, her abortion at 26. Or the self-explanatory My Life in a Column, a collection of pieces written weekly for the Independent from 2005 until 2009, scattered with creative breakthroughs, hangovers, holidays with Kate Moss and affection for her cat, Docket.

That we know the stories behind the art – if product and context can really be divided so cleanly – is down to Emin’s openness in sharing them. It’s an exploration of self that feels intrinsic in 2019 but for Emin has been met with resistance since she rose to prominence as part of the Young British Artist movement alongside Sarah Lucas and Damien Hirst; a woman who wears her traumas candidly, who has chosen art but not children, talks about sex and has drunk to excess, up against a tabloid press.

Many of those voices have described Emin’s output as confessional, but that would assume a bid for absolution from some outside entity. Instead Emin plies her emotional landscape, inquisitive and alone, until vulnerability becomes a defiant celebration of humanity.

In knowing her heartbreaks, we share her victories, too.

Though Emin is self-sufficient in her inspirations (as she put it, “Picasso had to use other people, I can use myself”) she has been enduringly generous with her discoveries, whether divulging how it feels to grow physically, sexually and emotionally older, or sharing, with empathy, ‘The Proper Steps for Dealing with an Unwanted Pregnancy’, as she does in Strangeland.

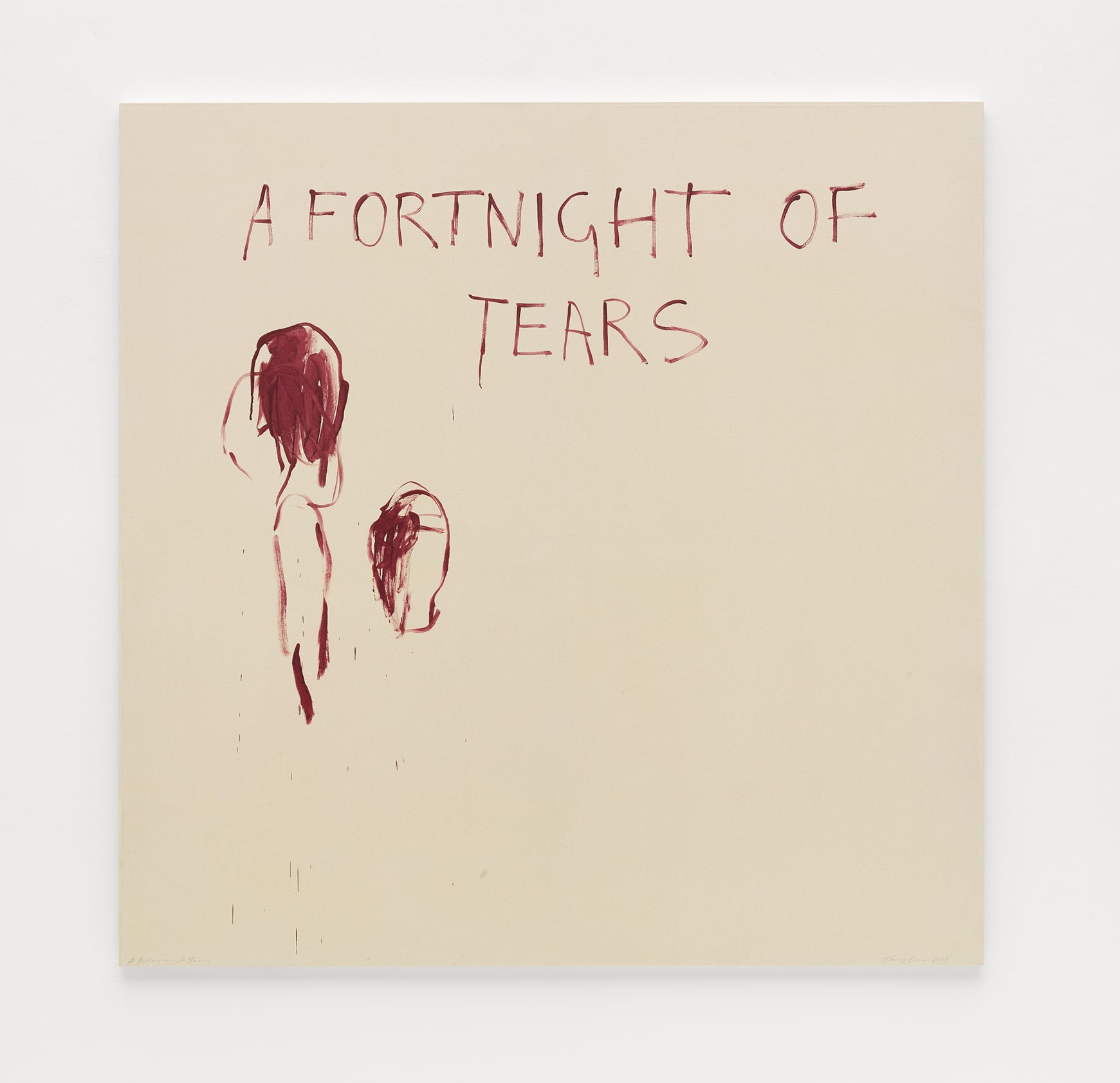

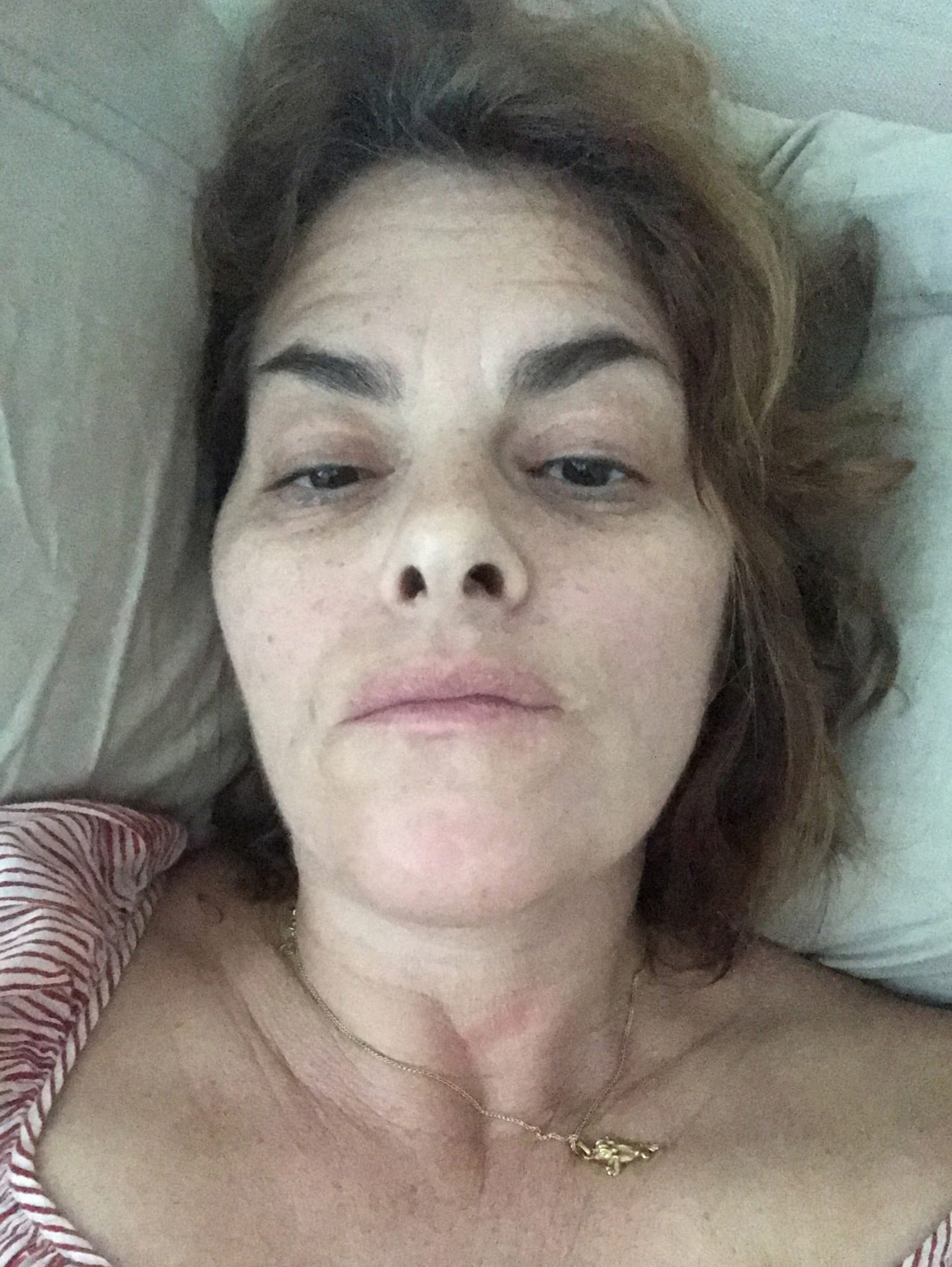

Emin has credited her traumatic first abortion in 1990 as the catalyst for her life’s work – with all that came before it destroyed by the artist – and it’s an event she returns to in her new exhibition at White Cube Bermondsey, entitled A Fortnight Of Tears. Thematically, the show is reflective of its naming: musings on grief, memory, loss and spiritual (not sexual) love. Along with a series of self-portraits taken on Emin’s iPhone when those stirrings prevented sleep, it encompasses painted works, Emin’s largest bronze sculptures to date, and her 1996 film How It Feels, made in response to her two abortions – chosen because it signifies not only her pain but her propensity to heal.

In the midst of preparing for A Fortnight of Tears, Emin spoke to RUSSH for our Heartbreak Issue about creating for herself, love as a cure-all and art that’s better than sex.

Your upcoming exhibition at White Cube Bermondsey brings together photography, large-scale sculpture, film, neon text and new paintings. Collectively, what do these works mean to you?

The work represents how I live, breathe and feel. It’s like my mirror.

Is there an event or notion that feels central to the works created in the past year?

I am still grieving for the loss of my mum. I am trying to understand death, but I think it’s impossible.

The exhibition notes cite spiritual love as a central theme. What does spiritual love mean to you, and why is it necessary to define it as such?

Because I don’t have physical love and haven’t for years and years, I still have to find a hierarchy within love.

"I wanted to show what makes me cry, and what has made me cry. I stopped painting when I was pregnant in 1990 because I felt like such a failure ... It’s really good to show how much things can change."

How has the way you think and feel about your abortions changed, or remained, since How It Feels was first shown in 1996?

My opinion is still exactly the same. I have no regrets. I know I did the right thing but never the less due to my beliefs I have always felt very sad about it.

You have spoken of art as a life force. How do you experience that when you are creating?

Sometimes if I am lucky, I feel like a whirling dervish and an insane banshee, casting spells and reinventing my own universe. It’s one of the most exciting things in the world. It’s better than the best sex, but when it’s bad, the overwhelming feeling of failure can drive me to despair.

Why did you choose photography as a medium in documenting your insomnia, in the series to be shown as part of A Fortnight of Tears? Did recording this impact the way you experienced it?

When you have insomnia you can’t sleep at night, in fact you can’t do anything. Picking up my phone and taking a picture of myself is as much effort as I can achieve. Anything more would be working, and if I was working at night, it wouldn’t be insomnia.

Do you remember when you first realised art could be a form of catharsis?

I’ve always written so I always knew that being clear with your own emotions was a good thing, but what worries me is that because I am so open about everything, there is still so much that is underneath the surface one day I think it’s going to explode.

Proust said “we are healed from suffering only by experiencing it to the full”. Does your process of returning to painful events via your art relate to this notion?

I wish I didn’t have to suffer.

What is your greatest motivation?

Being an artist.

What are you most proud of?

Being an artist.

Is it ever possible to truly heal heartbreak, via art or otherwise?

I made a neon once that said ‘It’s different when you are in love’.

"The feeling of love can cure and mend so many things, but the fear of a broken heart can be more damaging than a broken heart itself."

All images © Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS 2017. Photos courtesy of the artist and White Cube (Theo Christelis). Tracey Emin: A Fortnight of Tears runs at White Cube Bermondsey from February 6 to April 7, 2019.