Olivia Laing is a woman after our own hearts. Her art criticism for Frieze was immortalised in 2020’s chart-topping book of essays Funny Weather—an examination of everything from the enduring appeal of Jean-Michel Basquiat through to the legacy of alcoholic female writers like Patricia Highsmith, and the timeless genius of John Berger. It was a veritable literary treat for the lockdown-bound who had become fans of Laing’s work in her earlier books, the non-fiction hits The Lonely City, Echo Spring, and To The River, and her 2018 novel Crudo, a modernised take on Christopher Isherwood’s Goodbye to Berlin, set in the south of Italy during the halcyon days of the Trump administration.

Last week her latest offering, Everybody, landed on shelves in Australia. Much like Laing’s other works of non-fiction, Everybody is a sprawling odyssey drawing on a disparate collection of counter-cultural figures from the 20th century to explore the ways in which bodies are inherently political. Bringing together Susan Sontag and Andrea Dworkin to Nina Simone, Malcolm X, and Sigmund Freud, Laing explores the way the body stores trauma, investigates the impacts of imprisonment on the human psyche, and examines the many ways sex and politics continue to interact. Here, we speak to Laing about her remarkable new work.

Congratulations on the release of Everybody, it’s brilliant. You seem to have this strange ability to predict cultural moments with your books. Funny Weather was a book of essays about how art functions in emergency and was published the week we went into global lockdown last March. And now Everybody, which is about how our bodies are inherently political, is being released as the verdict in the Derik Chauvin trial is being announced, and as we’re all negotiating life after lockdown…

It’s quite eerie. I felt it really intensely with Funny Weather, because, as you say, the subtitle was ‘Art in Emergency’ and it was published literally as we were entering one of our biggest global emergencies in recent memory [last March]. And with Everybody, it’s coming out right as we’ve had this massive experience of physical vulnerability that a lot of people—because of their race, because of their gender, because of their class—experience all the time. Covid has made people who were protected from that kind of awareness realise how vulnerable their bodies are, how communal our bodies are, and how we are open and porous in ways that we didn't perhaps expect. But I guess that's what an artist is supposed

to do, right? You're supposed to be making sense of cultural, political trends as they start to emerge into view.

Something I realised reading your book is that the more privileged you are, the longer you’re able to make it in the world without realising the political implications of your body. For example, friends of mine who are of colour say their first experiences of racism happened when they were only very young children, and women tend to find they are sexualised as they hit puberty. When was that experience for you?

For me, that realisation came incredibly early. When I was a child, a law called Section 28 was passed in Britain that said that the kind of family I grew up in—a gay family—was a pretend family. This was the same moment as the AIDS crisis, so my family structure was immediately politicised. I was growing up in a queer community that felt grievously imperilled, and it was a foundational experience. But it was also an awakening to somebody [like me], who wants to think critically about the culture that we’re in.

You were also heavily involved in environmental protests in the ‘90s. How do you feel seeing where we’re at now?

It's incredibly distressing to think that we were trying to do something about climate change at a point where climate change could have been prevented. [Back then], it could have been much more easily handled. We were trying to speak and to act, and that was being absolutely ignored and stonewalled. I mean, it’s heart-breaking.

Malcolm X and Nina Simone feature in Everybody. How did you feel seeing the Black Lives Matter protests last year, after having spent so long immersed in the work of those original civil rights leaders?

It felt thrilling to me, it felt extraordinary. It was moving to watch people protesting with masks on during a pandemic. But it was also very interesting to be watching that having spent the last few years writing about the civil rights movement. In some ways, nothing changes, and in some ways things have become worse. A part of the impetus with Everybody is how do you not give way to despair when we still are fighting the same battles? When these battles go on and on forever? And I think the conclusion I came to about that is, if we think that we will achieve liberation and that will be it forever, we are going to be disappointed. But if we think of it as a case of doing our part, and contributing to something that is multi-generational struggle, then it's easier to stay hopeful and to stay active.

Everybody centres a lot around the work of Wilhelm Reich, a Freud protégé that I was first introduced to in the Kate Bush song ‘Cloudbusting’. When were you introduced to Reich’s work? What excited you about him?

I feel like I've made a career out of writing about complex and difficult people, but Reich is absolutely the most complicated and difficult of them all. He was very hard to write about. He's somebody who has the most extraordinary illuminating ideas, and at the same time, terrible ideas. He's somebody who, in some ways is a very admirable character, but also did some appalling things. He was Freud's most brilliant protégé, and he tried to unite the work of Freud and Marx. He believed that trauma was embedded in our bodies, that the emotional experiences we have live on in our bodies, but at the same time, our bodies were agents for social change.

But then, after the rise of Hitler, he had a terrible breakdown. Freud rejected him, and he ended up in America, where he basically became a kind of pseudo-scientist. He ended up in prison and died in a prison cell. Over time I became quite obsessed with him. And I think it’s because his life and work look at the body through many different lenses—it brings in sexuality, illness, and activism. I didn't want to write a biography of him, I definitely wanted to bring in other characters, but he was a way of traveling through the psychic and political aspects of the body.

Reich’s work has informed broader scientific research about the connection between the body and trauma, including the best-selling Bessel van der Kolk book The Body Keeps The Score. It seems like his positive work has been overshadowed by the negatives, and that he hasn’t ever really been given his dues.

I think that’s because sexuality remains challenging. Because he was talking about sex, he got stuck in history as the ‘orgasm man’, and people like Norman Mailer loved him. But when you read his work, it's actually it's a critique of patriarchal capitalism—he’s talking about ending violence toward women. He's talking about abortion rights. He had these incredibly radical ideas, which is why Andrea Dworkin loved him. I think it's a tragedy that his work is disparaged as ‘He just wanted orgasms’, because what he's really talking about is an erotic life for women that isn't entangled with violence. That’s a revolution that we still haven't gotten to in 2021. It's 100 years later.

I was fascinated to read your essay on Andrea Dworkin, because I had a very two-dimensional view of her work. I dismissed her as this aggressive, anti-porn kind of radical feminist, but her work is much more complex than that.

I had a cartoonish sense of Dworkin too. I heard her speak in the 90s, and I felt very much that I was on the other side of the porn wars. I didn't agree with her, and found her to be quite a repressive speaker. But I came back to her work in the last few years, when Johanna Fateman edited the collection Last Days At Hot Slit. So I read that, and her voice is extraordinary. It's an incantatory, frightening, witty, amazing, not-like-anybody-else voice. I didn't realise she was so funny. I didn't realise she was so wide-ranging. I didn't know that she'd been in abusive marriage.

I wanted to write about sexual violence, and she went there, she really looked at that subject with very, very clear eyes, very courageously. The message she brings back from those states of hell are very uncomfortable to read. There are things that she said and thought that were un-palatable, but at the same time, it's very painful to recognise what happens to women's bodies, what happens to people who are embedded in women's bodies, and that those experiences haven't stopped. To see the Reclaim the Night stuff that's happening right now, these are Dworkin’s battles, and we're still fighting those battles.

I’m not sure if this is something you’re thinking about at all, but I was reading Everybody just after I’d read a few stories about the spike in post-pandemic Botox and plastic surgery. I know we’ve spent so much time on Zoom this year, but it feels kind of remarkable to me that we’ve just had this international health crisis, but it doesn’t seem to have hasn’t shaken our obsession with our external appearance at all. Do you have any thoughts on that?

It does seem to me that they're completely related. A mass revelation of physical vulnerability and physical terror is immediately followed by people wanting to make that outer shells protectable—it’s armour. I think there's something psychological, where we want to be able to go back into the world feeling secure and safe and impervious in some way, because we've just had this revelation of how impermeable we are. So, I think that it is linked, and it does make sense.

Your art criticism is the first I've read that has felt like it’s simplifying fine art rather than complicating it. There’s something really democratising about the way you write, because I’ve found that a lot of art criticism seems almost intended to be impenetrable, which becomes a kind of elitist gatekeeping around who's supposed to enjoy art. Is that something you’ve done on purpose?

Absolutely. I think that jargon creates a kind of smokescreen, and it's often completely vacuous as well, it sounds like it's very intelligent, because it's got theory speak, but it's completely devoid of ideas. I also think it's very patronising to think that ordinary people can't think about complicated ideas about art. It's my

job as a critic to communicate that in ways that are straightforward, but the ideas should be really interesting, involving, engaging and even difficult—but you don't have to use difficult language to make that happen. You can use everyday language. My art criticism draws so much on Frank O’Hara and the New York School, where they’re talking about abstract ideas, and complicated, difficult works, but they're using a conversational, gossipy, chatty tone. There's absolutely no reason why you can't do that.

Something that was a huge thread throughout Funny Weather was the idea that pursuing hope isn’t naïve, but an important act of self-preservation, and essential to the preservation of social movements. the movement going. How have you stayed hopeful this year?

Writing Everybody was, by the end, hopeful, even though it was an incredibly depressing and quite dark journey at times. It gave me that sense of how movements continue beyond a single human life. As an individual you don’t need to succeed so much as you play your part. When we think about things in networked ways, it becomes a lot more relaxing, and easier than if you think of everything in terms of the striving self that has to constantly achieve something. That’s helped me a lot. And then the other thing, very practical is, I spent a lot of time gardening. With gardening, there's no moment of success, you're just contributing to something. And that sense of contribution feels to me like a lot better way of working than victory. Contribution rather than victory.

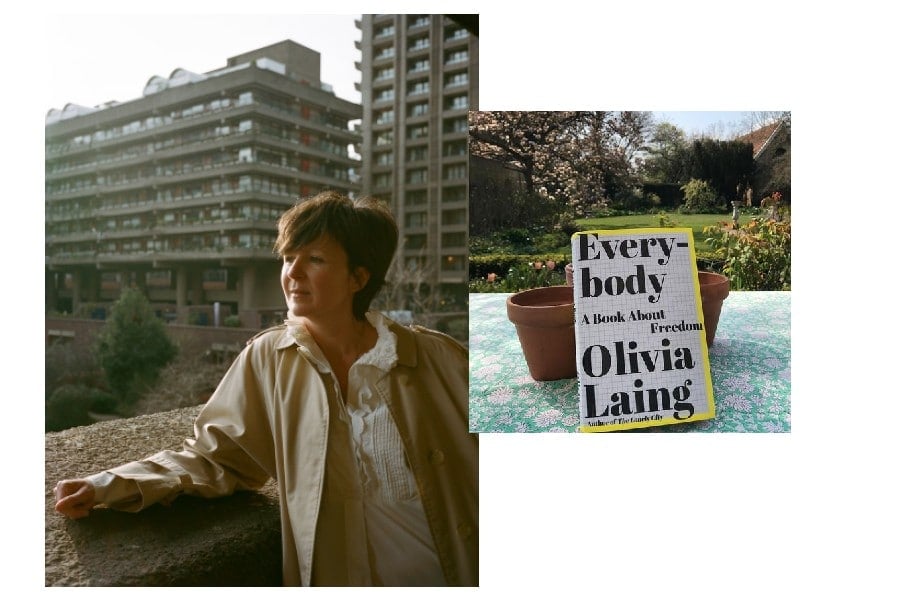

Images: Olivia Laing